The author gave this commencement address at the School of Visual Arts on 19 May 2013.

I’m not here today to offer advice or even encouragement. I’m here to talk about art and audience, about art and the people it reaches—and what happens when it does.

I’ve always believed that the divisions between high art and low art—between high culture, which really ought to be called sanctified culture, and what’s sometimes called popular culture, but ought to be called everyday culture—the culture of anyone’s everyday life, the music I listen to, the movies you see, the advertisements that infuriate us and that sometimes we find so thrilling, so moving—I’ve always believed these divisions are false.

And as a result of trying to make this argument over the years, I also believe that these divisions are permanent. They can be denied, but they will never go away.

The Museum of Modern Art here in New York dramatized this quite fabulously in 1990 with a show called “High and Low.” It presented extremely famous pop art paintings—the high art—next to their pop culture sources, their low art sources—Philip Guston and Roy Lichtenstein “Krazy Kat” or “Steve Canyon” or “True Romance” paintings next to “Krazy Kat” comic strips and “Steve Canyon” and “True Romance” comic books.

The pop art paintings were definitely bigger than the comics panels—more dramatic. For that matter, more vulgar. But I couldn’t understand then, and I don’t understand now, why George Herriman’s “Krazy Kat” strips or the comic books produced by anonymous writers and inkers and graphics people were lesser art—really, why they were not better art, the real art—than the pop art classics Philip Guston and Roy Lichtenstein had made of them.

Nearly everything I’ve written is based on the conviction—the experience and thinking about it—that there are depths and satisfactions in blues, rock & roll, detective stories, movies, television, as rich and as profound as those that can be found anywhere else.

Who, really, could argue that the sense of transportation, even in the religious sense—the taking of oneself out of one’s self, connecting the self to something greater, something, you know in the moment, in your heart, that every person who was ever born must experience or be left incomplete—who could argue that that sense of transportation is not as present in the Rolling Stones’ “Gimmie Shelter,” or in the scene in “The Godfather” when the camera is moving in on Michael Corleone, so slowly, and Al Pacino says, “And I’ll kill them both,” as in any art—the most exalted in motive, the most revered in history?

Well, I believed all that when one day in 1996 I walked into the Basilica di Santa Maria Gloriosa dei Frari in Venice and saw Titian’s sixteenth-century “Assumption of the Virgin”—an altar-place painting of the Virgin Mary being borne up to heaven by scores of angels while people on the earth reach up to her, God looks down, and the woman in the middle is caught somewhere between deliverance and terror.

The picture is more than 22 feet high and more than eleven feet wide. It’s so big you can’t see it all at once—big in size, but big in every other way, too. I was stunned. I thought I knew something about art—I’d seen paintings all over the U.S. and Europe. I’d been moved to tears by some and scared by others. I’d seen hundreds of movies, listened to thousands of albums, some of them hundreds of times. I thought I knew something about art, and in an instant I realized I knew nothing.

I was transfixed. Again and again, I walked back and forth in front of the painting. I stopped and looked up at it. I walked to the back of the church to see it from a distance. I walked up to the base again.

I kept trying to leave the building, and every time I reached the door I found myself pulled back in. I couldn’t get out; I was trapped by revelation.

Yes, I said to myself, finally I understand. The only great art is high art. But it didn’t stop there. No, I realized, there’s more. The only great art is high art, and the only high art is religious art, and the only truly religious art is Christian art. Three things I don’t believe—and I was reduced to a puddle of acceptance. I can’t believe I got out of there alive.

I got over it. But that day stayed with me—as a proof that what art does, maybe what it does most completely, is tell us, make us feel, that what we think we know, we don’t. There are whole worlds all around us that we have never seen.

My sense of what art is and what it does in the world was spelled out by the late filmmaker Dennis Potter. He understood that there are worlds of art that we don’t see—and he understood, just as importantly, that there are worlds of art that people live in, live in fully, to the depths of emotion, that other people refuse to recognize.

Dennis Potter wrote the 1981 Steve Martin Depression musical Pennies from Heaven, and the fabulous BBC TV musicals The Singing Detective, from 1986, and Lipstick on Your Collar, from 1993. In these musicals people don’t just break into song. Old songs descend on them like visitations, and the original recordings come out of their mouths and change them. The actors are lip-synching, but it feels not as if something is being faked but as if something real, real but never glimpsed before, is being revealed—is being set loose in the world.

What were the songs? Pop songs from the 1920s into the 1960s. “It’s a Sin to Tell a Lie” by Dolly Dawn. “Little Bitty Pretty One” by Thurston Harris. “Don’t Be Cruel” by Elvis Presley. “Ac-Cent-Tchu-Ate the Positive” by Bing Crosby. “Pennies from Heaven” by Arthur Tracy. Dozens more, some remembered, more forgotten. “How do I get that music from way down there [to] bang up front,” Potter said once. “And then I thought, they lip-synch things. I wasn’t breaking a mold, I found the ideal way of making these songs real.” It was the obvious artifice—sometimes a man’s voice coming out of a female character’s mouth—that let the truth of the songs, and the characters, feel irreducible.

And, coming out of the experience of making these pictures, this was Potter’s manifesto, from an interview he did with the film critic Michael Sragow in 1987:

I don’t make the mistake that high culture mongers do of assuming that because people like cheap art, their feeling are cheap, too. When people say, ‘Oh, listen, they’re playing out song,’ they don’t mean, ‘Our song, this little cheap, tinkling syncopated piece of rubbish is what we felt when we met.’ What they’re saying is, ‘That song reminds me of the tremendous feeling we had when we met.’ Some of the songs I use are great anyway, but the cheaper songs are still in the direct line of descent from David’s Psalms. They’re saying, ‘Listen, the world isn’t quite like this, the world is better than this, there is love in it,’ ‘There’s you and me in it,’ or ‘The sun is shining in it.’ So-called dumb people, simple people, uneducated people, have as authentic and profound depth of feeling as the most educated on earth. And anyone who says different is a fascist.

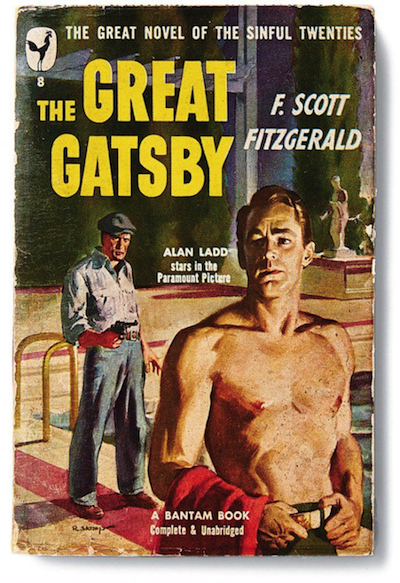

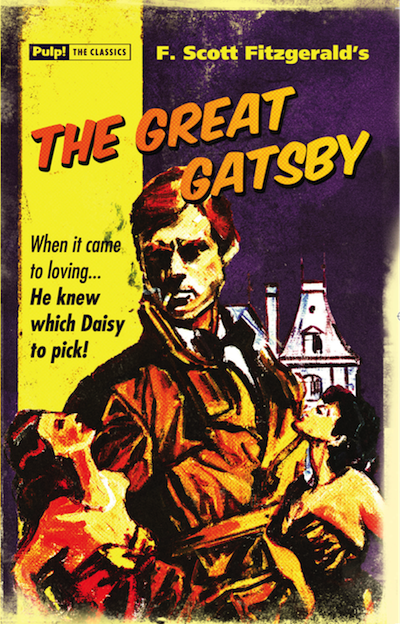

There was an example of this kind of fascism in the New York Times, just two weeks ago, in a front-page story called “Judging Gatsby by Its Cover(s).” Because of the new movie version of The Great Gatsby by Baz Luhrmann, which is opening tomorrow, there were two new paperback editions of the book—the explicit, vulgar movie tie-in edition, with a picture of Leonardo DiCaprio as Gatsby on the cover, and the unspoken movie-tie in edition, with the original 1925 spooky-eyes cover art. The story was about which stores, like Walmart, were carrying only the DiCaprio edition, and which were only carrying the other one. The writer of the story, Julie Bosman, interviewed a book buyer named Kevin Cassem of the New York independent bookstore McNally Jackson, on Prince Street in Soho. “It’s just god-awful,” he said about the movie edition. He went on: “The Great Gatsby is a pillar of American literature and people don’t want it messed with. We’re selling the classic cover,” he said—despite the fact that for decades the paperback Gatsby had a simple print cover, and the original art was forgotten—“and have no intention of selling the new one.”

The writer apparently caught some hint in what Kevin Cassem was saying—maybe it was that “people don’t want it messed with,” whether that meant his kind of people, the kind of people who shop at McNally Jackson, or the kind of people McNally Jackson people like to think shop at McNally Jackson, or whether Cassem felt perfectly fine about speaking for everyone who’d ever read the book—the writer apparently caught some hint of something she didn’t like.

She asked Cassem, in her words, “whether the new, DiCaprio-ed edition of Gatsby would be socially acceptable to carry around in public”—and Cassem took the bait. “I think it would bring shame on anyone who was trying to read the book on the subway,” he said. So American literature is, so to speak, for people who know how to dress properly? It’s better not to read the book than to read it with the wrong cover? Or is Kevin Cassem going to become the literary Bernie Goetz?

What he’s really saying is that people on the subway reading The Great Gatsby with the wrong cover aren’t good enough for the book—and that is exactly what Dennis Potter meant when, just like that, he brought the hammer down with that hard, blunt, I-mean-exactly-what-I’m-saying sentence, “Anyone who says different is a fascist.”

“I think we all have this little theatre on top of our shoulders,” Potter said that same day in 1987, seven years before he died, “where the past and the present and our aspirations and our memories are simply and inevitably mixed. What makes each one of us unique is the potency of the individual mix.”

For a moment, in that church in Venice, all of that was in ruins—but that’s what art does. That’s what it’s for—to show you that what you think can be erased, cancelled, turned on its head, by something you weren’t prepared for, by a work—a play, a song, a scene in a movie, a painting, a collage, a cartoon, an advertisement—that has a power that reaches you far more strongly than it reaches the person standing next to you, or even anyone else on earth. Art that produces a revelation that you might be unable to explain or pass on to anyone else—but a revelation that you will desperately try to share, in your own words, or in your own work.

What is the impulse behind art? It’s saying, in whatever language is the language of your work, if I can move anyone else as much as that moved me—that “Gimmie Shelter,” that scene in The Godfather, that painting by Titian—if I can move anyone even a tenth as much as that moved me—if I can spark the same sense of mystery, and awe, and surprise as that sparked in me—well, that’s why I do what I do. And this is why, in 1947, just after the Second World War, Albert Camus said, as plainly as Dennis Potter, “There is always a social explanation for what we see in art. Only it doesn’t explain anything important.”

Most explanations of art—of what art is, of why people make it, of why some art leads to great success, in other words fame and money, and some doesn’t—are meant to reduce art to something that can be easily explained, that can be easily understood—and most explanations of art are meant to exclude a lot of art, and a lot of people.

This came home for me a few years ago when I was reading a collection of essays about Allen Ginsberg’s poem “Howl,” first read publically in 1955, published in 1956—almost every one about how the poem had changed the writer’s life. This poem changed my life, one writer after another testified—which is why the word I appeared in the first or second line of more than half the pieces in the book. It reminded me of a person who once rushed up to the film critic Manny Farber—who was one of the crustiest, unsmilingest people you’d ever want to meet, or not want to meet—and said, “Mr. Farber, you changed my life.” “I doubt it,” he said. Life is not that facile, he was saying.

This poem changed my life, the writers said over and over. “Can I possibly convey,” said one, “how those words”—he’s talking about the first lines of “Howl,” “I saw the best minds of my generation destroyed by madness, starving hysterical naked / dragging them through the negro streets at dawn looking for an angry fix”—“how those words moved in me, how that cadence undid in a minute’s time whatever prior cadences had been voice-tracking my life?” No, he can’t. Nobody could convey anything in writing that flat and contrived: “that cadence,” “whatever prior cadences,” “voice-tracking.” But writer after writer is telling you how the poem changed his life, her life—that is, how it made them writers. Which is a kind of fascist vanity, fascist in the way it erases what the writers are supposedly talking about: If this poem produced a writer like me, it must be good!

It all comes down to that urge to fascism—to know what’s best for people, to know that some people are of the best and some are of the worst, the urge to separate the good from the bad and praise oneself, to decide what covers belong on what books people ought to read, what songs they ought to be moved by, what art they ought to make—an urge that makes art into a set of laws that take away your freedom, rather than a kind of activity that creates freedom, or reveals it. It all comes down to the notion that, in the end, there is a social explanation for art, which is to say an explanation of what kind of art you should be ashamed of. It’s the reduction of the mystery in art—where it comes from, where it goes—to the facile explanation of that poem made me a poet!—as if why anyone is a poet, or not a poet, is something that can be explained at all.

At the end of that collection of pieces on “Howl,” there was one by a man named Bob Rosenthal, who had worked for twenty years as Allen Ginsberg’s secretary. Only a fool pretends to know what happens when a poem finds a reader, he said—just as we are all fools if we pretend to know exactly why we do what we do, or what what we do actually is—where it comes from, and where it will go.

“‘Howl’ still helps young people realize their actual ambitions,” Rosenthal wrote—“not to become a poor poet living in a dump but maybe to become a physical therapist when you are expected to become a lawyer, or maybe to become a lawyer when everybody expects you to fail at everything.”

And anyone who says that is not a fascist.

Thank you.

Editor’s Note: Since Greil Marcus gave this address “he has seen The Great Gatsby twice and both times wanted to go right back into the theater when it was over.”