Novelist Jesymn Ward first posted this short meditation on what Obama’s rise meant in the deep South in 2008.

I almost didn’t vote for Obama in the primaries. I called El beforehand, and we had a very long conversation. I’m afraid, I told her, afraid that he will not be a viable candidate to beat the republicans because he’s black. And coming from Mississippi teaches you that being black carries a certain problem of perception. Of history.

Of learning that a white classmate would never stoop to kiss you, that security will follow you around in stores, that cashiers won’t touch your hand to take money, that older white classmates will threaten you with lynching, covertly, and that another will sit on your desk while your teacher is out of the room during a test, and he will tell nigger jokes. And nobody, not your classmates who will not drink after you, not your classmates who you’ve been in school with for at least two years now, and most of all not you because you know he wants to see you cry or freak out or yell at him, will say anything. But you look the other one that threatened you with lynching or beating or burning, with all of the ghosts of the south on his shoulders, his jock-buddies around him, him you looked in the eye and you said, no, you won’t do shit to me. Try me.

This is the history that squeezed into the corners of the conversation with El, that crowded the phone. This is blood dread, knowing that your mother and father both used to go to a segregated school, that your mother was so pretty and fair that she was chosen to integrate Pass Christian school, and that your father used to get chased from the Pass Christian memorial park by the gameskeeper when he snuck in the park. Get out of the park, you little niggers! This is bone memory, knowing that your great-great-grandfather was shot and killed by white prohibition patrollers, that somewhere in that mix of Indian-loving disowned Frenchman, rogue Spanish, wandering Native Americans in your bones, there are African slaves, passing along their memories of plotting poison and snatching joy in Congo Square.

I don’t know if I can vote for him, I said. I’m from the South. The white people I grew up with will never, never vote for a black man to be president. Never, I said. I should vote for Hillary. Go for the safer candidate. History turned circles like a nesting dog too big for its bed, laid down in my heart. Lapped up all the blood. Grew fatter.

And she told me: Believe. Who do you believe in? It can happen, Jesmimi. It can. And then I thought about how much I loved El, how we lived together those years, and we were just two people who shared pain and joy and hope and ideals. How we tried to make space for art, for truth, for beauty in our work. How she was so white she couldn’t tan, and I was so black my kinkycurly hair kept coming out in the bathtub and clogging the drain. How she wasn’t like these people I’d grown up with. And there were probably more of her, more people who faced the spectre of race bravely, shrugged it off, looked it in the face, lived with it, lived past it, lived in spite of it. Come on, El said. She gave me hope. Reminded me of the fact that that’s what nourished my daddy running through that damn park, my mama facing down those white kids, my grandmother when she was working her fingers to calloused nubs all those years to provide for her seven kids by cleaning white people’s houses, those slaves, those Natives. They’d eaten hope. Starved for it. Died for it. So I voted for him.

And so did you. And he won.

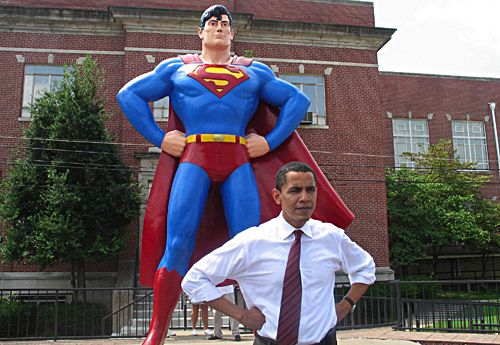

(On a lighter note, he is a nerd, as evidenced by the above picture, and I love him.)