(Gaza Feb 29 2024)

A small grey rectangle

The aid truck arrives

Iron filings converge upon a magnet

Ants swarming a dropped chocolate

They may have weapons

hidden in their skeletal hands

Their hunger may be explosive

A Website of the Radical Imagination

(Gaza Feb 29 2024)

A small grey rectangle

The aid truck arrives

Iron filings converge upon a magnet

Ants swarming a dropped chocolate

They may have weapons

hidden in their skeletal hands

Their hunger may be explosive

Today in Dakar, during the inauguration of Sénégal’s new president, Bassirou Diomaye Faye put on a heavy gold necklace signifying he was “Grand master of The Order of the Lion.” The ceremony made me think first of Les Lions — Sénégal’s national soccer team — but I also heard echoes of Shelley…

Rise like Lions after slumber

In unvanquishable number–

Shake your chains to earth like dew

Which in sleep had fallen on you–

Ye are many — they are few.

Faye’s party won a landslide victory, though he was released from prison just ten days before Sénégal’s March 24th election (after eleven months in pretrial detention on a bogus charge)…

A few hours after the polls closed, partial results were already pointing to a first-round winner: Bassirou Diomaye Faye, the candidate of the most outspoken opposition to the incumbent government, and second in command of the African Patriots of Senegal for Work, Ethics and Fraternity party (PASTEF). Faye will be the youngest and most unexpected president in the history of independent Senegal.

Before his presidential candidacy, Faye was little known to the Senegalese public, working in the shadow of party leader Ousmane Sonko. Sonko, also a former tax official [and another victim of a rigged judicial proceeding] … gained popularity, especially among young people, for his highly critical discourse on the traditional political class and for his promises of a radical break from how the country has been governed for decades.

I flashed on Shelley again when I saw this photo of the grey-haired Maitre Cire Cledor Ly at the inauguration…

Great philosophers can make great errors when they confront things that challenge their closely held beliefs. Theodore Adorno, a brilliant critic of classical music, wrote ignorant essays about pop and jazz. Noam Chomsky, whose work is fundamental to modern linguistics, has a naive grasp of how media operate. Michel Foucault, whose writing on discourses and authority shaped postmodern thought, regarded the Ayatollah Khomeini as a guide to liberation from Western materialism. And then there’s Judith Butler.

An editorial in Haaretz…

The fighting in Gaza must stop. Not tomorrow. Today.

All available resources must immediately be directed to stopping the unprecedented famine that is underway in that embattled sliver of land that has already seen unspeakable suffering. As bad as the Hamas attack on Israel on October 7 was, the people and government of Israel must now recognize that today not just the country’s security but its legitimacy are at stake as never before.

View this post on Instagram

View this post on Instagram

I used drugs—marijuana, LSD and ecstasy—in the Sixties but I never thought of them as therapeutic. The author, Seth Lorinczi, and his new autobiographical book, Death Trip, A Post Holocaust Psychedelic Memoir, has opened my eyes as never before to the idea that psychedelics can help heal the trauma of the Holocaust. In Lorinczi’s telling of the story, psychedelics rescued him, psychological speaking, from the legacy of Fascism, World War II and the extermination of millions of Jews.

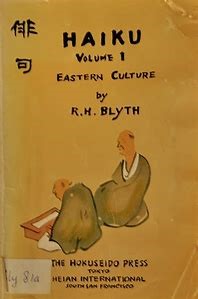

I found the first book of R. H. Blyth’s four volume set, Haiku, (originally published between 1949-1952) in a used book store on St. Mark’s Place. If haiku seems no more pertinent to you than, say, heraldry—one more subject about which even an informed person “need not be ashamed to know nothing”[1]—you may be mollified to hear I had an excuse to check Eastern Culture since I was Christmas shopping for a nephew who’s on his way to Japan this spring. The book’s cover—“Oriental brown simple rough peasant cloth”—got me to open “the Blyth Haiku bibles” (pace Allen Ginsberg, Allen Ginsberg). I fell in…

“Plop!”

To quote the last line of “the most famous haiku” with frog-and-pond as translated by Blyth—scholar-gypsy who brought the East to Beats and Salinger (see J.D.’s bow to Blyth in “Seymour, An Introduction”: “…haiku, but senryu, too…can be read with special satisfaction when R. H. Blyth was on them. Blyth is sometimes perilous, naturally, since he’s a highhanded old poem himself, but he’s also sublime.”)

This is a chapter from Blyth’s first book, Zen in English Literature and Oriental Classics.[1]

…

From Aristotle down to Arnold it was considered that a great subject was necessary to the poet. Arnold says that the plot is everything. It is useless for the poet to

imagine that he has everything in his own power; that he can make an intrinsically inferior action equally delightful with a more excellent one by his treatment of it.

Wordsworth stands outside this tradition by instinct and by choice. He chooses the aged, the poor, the idiot, the vagrant, but does not endeavour to make them “delightful” at all.

Excerpted from Kirkup’s introduction to The Genius of Haiku: readings from R. H. Blyth on poetry, life and Zen. Published by the British Haiku Society.

I first became aware of the works of Blyth in 1952 or 1953, when I held the Gregory Fellowship in Poetry at the University of Leeds. It was also a time when I when I was discovering Chinese and Japanese poetry and philosophy, and reading books on Zen Buddhism that were beginning to proliferate in those days, and to have a certain influence on the Beat poets of America. whom I barely knew, though I had heard of Ginsberg, Jack Kerouac and the City Lights poets. I was also reading the works of Daisetz Suzliki and Alan Watts, the gurus of the Beat Generation.

This chapter from Peter Linebaugh’s Stop Thief: The Commons, Enclosures and Resistance opens with aristos’ charming spin on the human right to rest. But Linebaugh isn’t one to go on in defense of laziness. Near the end of this short piece, he invokes bookish Reds who once insisted a “Communist is a mere bluffer, if he has not worked over in his consciousness the whole inheritance of human knowledge.”[1] Linebaugh has surely put in work on that score. The fact that his essay is a preface to the Korean edition of one of his earlier books stands as a tribute to his worldliness. Linebaugh goes wide in this chapter (as ever) though he begins in bed…

Of the aristocratic and stylish Mitford sisters, Jessica provides us with the Lazy Interpretation of Magna Carta beloved by sluggards everywhere. As a lovely communist (two of her sisters were fascists) she was disowned by her family and fell from the social peaks of English aristocracy to the Dickensian depths of the Rotherhithe docks in London in 1939. Unable to pay the rent she and her husband lived in fear of the process-server who they avoided by going in disguises which the process server soon came to recognize. “Esmond had a theory that it was illegal and in some way a violation of Magna Carta to serve process on people in bed.”[1] So they stayed in bed all day and then all night, and again all the next day, and all the next night under the covers, before deciding to immigrate to America. (Tom Paine, too, thought that independent America was a realization of Magna Carta).

Macky Sall — Sénégal’s outgoing president (Inshallah) — has played one Trump card after another over the past year, as he’s tried to retain power. Sall got brazen about his contempt for his country’s democratic process a couple years ago when he started hinting broadly that he would run for a 3rd term, though that’s illegal under Sénégal’s Constitution which only allows a president two terms in office. He prepped for what he assumed would be his permanent ascendancy by defaming and jailing his main political opponent, a young firebrand named Ousmane Sonko who’s been exposing corruption among Sénégal’s political class for more than a decade.[1] When Sonko and his partisans refused to fade out quietly, Sall came out as a petty Big Man trashing the country’s (relatively) free press, unleashing violence against protestors and conflating democratic dissent with Islamist terror.

Originally published on February 14 at Notes from the Underground.

The Russian regime has finally extinguished the life of Alexei Navalny. Navalny was being held in a remote labour camp and, according to the prison authorities earlier today, died while taking a walk — like you do.

why do it in poetic form?

because in an infinite variety of ways

that reside in the breasts of all living souls

any solution to the Fascist trend in all states

pulses and grooves inside each of us

we hear the basic call of consciousness & conscience

Linebaugh’s principles made your editor rethink my attachment to “public happiness” — a phrase of Hannah Arendt’s that I’ve leaned on to evoke the excitement of (small d) democratic politics with its imperfectly human meld of egotism and solidarity. Linebaugh isn’t an Arendt man and he’s never been charmed by her hymns for the American Revolution. Aware our first Founding slipped slavery and the “Social Question” — all the challenges arising from mass poverty and de-skilled labor due to the Industrial Revolution — he’s unenthralled by America’s standard versions of democratic practice. Per Peter, public life/happiness in this country seems a straightened thing…

We distinguish “the common” from “the public.” We understand the public in contrast to the private, and we understand common solidarity in contrast to individual egotism.

While it’s probably wrongheaded to yearn for demos with no ego, Linebaugh’s distinction is coming through to me this morning. In my inbox today, there’s an announcement of the latest seminar aimed at (what one pale academic muckety-muck terms) “intellectual publics.” Like Linebaugh, I prefer more common things…

An essay in last month’s Town Topics, a Princeton gazette, begins on target: “This is an anniversary year for Franz Kafka, who died on June 3, 1924—a doubly noteworthy centenary, given the immensity of the author’s posthumous presence, which suggests that if ever a writer was born on the day he died, it was Kafka.”[i] Given that “immensity of presence,” one would be hard put to define concisely its core significance. But I will attempt to get to that core by example—the core being the difficult beauty of Kafka’s writing, a beauty that is full of thought, and which has inspired, as is well known, a great variety of attempts to understand it. For Theodor Adorno, in a celebrated essay, satisfying the need to understand Kafka is a matter of life and death!

Like many Jews, I’ve read things about the bombing of Gaza, seen things on TV, and heard things shrieked in the streets that have horrified me in starkly contradictory ways. The truth about this awful sequence of events is as hard to come by as it is complex, but the slogans mask as much as they proclaim, and the coverage does something even more ominous: it simplifies. Every day I’m glued to my TV, gripped not just by the unbearable images that the carnage has produced, but also by the stimulation of my senses, the spectacle of mass death. It’s what I’d call visceral news, which compels me to watch, and it’s all true. But it’s not the truth. That requires context, which isn’t a visual.

As soon as I heard the verdict of the International Court of Justice last week and heard the vote of 15-2 against Israel, I knew it had to be a woman. Who else could stand up to 15 men and vote with the old Israeli man?

I have been reading and writing poetry ever since I was a boy growing up in Huntington, Long Island, not far from where Walt Whitman was born and raised, and where he founded the newspaper, The Long Islander, which published my column on high school sports. At the age of 82, I still turn to poetry more often than to newspapers for news of the world, local, national and international. Recently, I read and reread the timely and (perhaps) timeless poems about Gaza in Mosab Abu Toha’s Things You May Find Hidden in My Ear, published by City Lights.

That book appeared in print at about the same time that the author and members of his family, including his wife and children—and thousands of other Gazans—were detained by Israeli soldiers. Fortunately, Toha’s wife and children were released and allowed to travel to Egypt where the poet joined them, and then wrote and published an eye-opening account of his own harrowing arrest, incarceration, and interrogation. That narrative was published in January 2024 in The New Yorker. In a short time, it has alerted readers around the world to Toha’s poetry and to his own newsworthy story.

Twitter dialogue between…

Fania Oz-Salzbarger [“Mom, Israeli, Jewish, humanist, History prof. Loving daughter of Amos Oz. Tel Aviv U (BA, MA), Oxford U (D.Phil), Uppsala U (Dr. h.c) Democracy must win.”]

&

Ambassador Majed Bamya [“Deputy Permanent Observer of the State of Palestine to the UN, New York. Palestinian from Yaffa. Refugee. The time for freedom is always right now!”]

From the Anarchist Library—first published on July 30, 2015.