Greil Marcus’s new book on Bob Dylan opens with a Dylan quote—“I can see myself in others.”—from a loose press conference with journalists in Rome in 2001. I recall listening to audio of that same rap session on YouTube and noticing another line that’s not at odds with the one that jumped out at Marcus. Dylan responded to a convoluted question with his own humorous query: “Am I an idiot?” he asked. This wasn’t a mid-60s prickly (Neuwirthy?) tease. While Dylan was playing to the crowd and encouraging them to laugh with him, he wasn’t coming hard at his questioner (who seemed to take his soft goof well). What struck me was that Dylan, even though he was only acting as if he was clueless, seemed entirely alive to how it might feel to be hopelessly at sea mentally. After all, he’s known what it was to be an unworldly Midwesterner at a Village party with an older generation of haute-bohos. (“I was hungry and it was your world.”) And that, in turn, puts him a thousand thought-miles away from heads who act like they’ve been tenured since they were ten. Dylan’s less presumptuous way in the world has enabled him to evoke what it’s like to be “invisible” in New York City or (even) “a pawn in their game” down home. Dylan has looked back tenderly on boy-genius Bobby (his younger self reminds him of “nature boy”) but he tends not to mix up his natural-born quicktoitiveness with surety that he is necessarily superb.[1] Dylan is aware he’s been a dummy—morally and otherwise—in his day. (See Truscott here on “Idiot Wind’s” ender.) Dylan is not one for false modesty. (“I know what I’ve done,” he stated at one point in Rome when someone asked him about the nature of his fame.) But his ironic self-check at the press conference hints at the high-low range of his empathy, which is a thread Marcus traces in Folk Music.

Much of the book is given over to Dylan’s close imagining of Americans on both sides of the color line in the early Sixties. It’s possible Marcus might’ve been spurred on here by Christopher Ricks’ prompts. Marcus and Ricks were both on a panel at Columbia a few years back where Ricks dug into Dylan’s early talking blues-ish performance of “The Black Cross.” Originally done live in the Fifties by Lord Buckley, it was adapted from a poem by Joseph Newman (uncle of Paul Newman). Dylan plays all the parts in the story of Hezekiah Jones—a black farmer in Jim Crow Arkansas who scandalizes white folks by spending all his money on books (which he keeps in a cupboard he calls his rainy season):

The white folks around the county there talked about Hezekiah

They…said, “Well…old Hezikiah, he’s harmless enough,

but the way I see it he better put down those goddam books.

Readin’ ain’t no good, for nigger is nigger.”

The white man’s preacher visits Hezekiah:

He says, “Hezekiah, you believe in the Lord?”

Hezekiah says, “Well, I don’t know, I never really SEEN the Lord,

I can’t say, yes I do…”He says, “Hezekiah, you believe in the Church?”

Hezekiah says, “Well, the Church is divided, ain’t they,

And…they can’t make up their minds.

I’m just like them. I can’t make up my mind either.”He says, “Hezekiah, you believe that if a man is good Heaven is his last reward?”

Hezekiah says, “I’m good…good as my neighbor.”“You don’t believe in nothin’,” said the white man’s preacher.

“You don’t believe in nothin’!”

“Oh yes, I do,” say Hezekiah,

“I believe that a man should be indebted to his neighbors

Not for the reward of Heaven or fear of hellfire.”

The skeptic paid in full for his belief.

“But you don’t understand,” said the white man’s preacher.

“There’s a lot of good ways for a man to be wicked…”Then they hung Hezekiah high as a pigeon.

White folks around there said, “Well…he had it comin’

Cause the son-of-a-bitch never had no religion!”

Ricks pointed out Dylan doesn’t do impressions in his version of “The Black Cross”; he acts the parts without ablating spaces between himself and the characters he embodies. Ricks rightly cites Dylan’s voicing of Hezekiah as a triumph of sympathy not identification.[2]

Ricks punctuated his case for Dylan’s musical theater by underscoring ugly laughter heard at the climax at one performance of “The Black Cross.” (You’ll have to take his/my word for that. There are a few versions of Dylan’s “Cross” on Youtube—you can hear one here—but I can’t find a recording with the superior chortles that Ricks steered auditors to at Columbia.) An early Sixties folkie crowd, stuck on its own pieties, had been enjoying themselves at the expense of rural Southerners and couldn’t stop the carnival when the antics weren’t funny anymore. Ricks zeroed in on their awful cool hilarity at the aural spectacle of a lynching.

That laughter might have gotten under Dylan’s skin—distancing him from his fans. The subject was closer to home/bone for him as Marcus makes clear when he links the opening of “Desolation Row”—“They’re selling postcards of the hanging”—to lynchings that took place in the Twenties not in the Deep South but in Duluth—Dylan’s neck of the woods.

Dylan didn’t just see himself in Hezekiah’s (or Aunt Hagar’s) people. He saw himself in their persecutors too. Meantime, there were those portions of the folk world that he had to see past to imagine the real. Along with yahoo-mockers who kept laughing when it was time for tears, there was a Silber-y smart set of career leftists who could open doors but not minds. Marcus has written lucidly about how Dylan’s “The Lonesome Death of Hattie Carol” put the last onus not on the aristo killer who murdered his black maid but on irreal certitudes of a righteous crowd who knew they were better than William Zantzinger. Marcus once used “Hattie Carol’s” “saddened, angry chorus” —arraigning “those who philosophize disgrace, and criticize all fears”—to soundtrack his critique of writers on the left who rushed to expatiate on 9/11 as New Yorkers were still breathing in the cloud of dead souls that floated around Manhattan in the aftermath.[3] In Folk Music—driven by the kind of progressive Reaction that Ricks highlighted—Marcus time-travels from a Sixties performance of “Hattie Carol” in New York to a version heard in Minnesota in our time where it sparks his protest against current styles of p.c. censoriousness.

When Dylan performed the song at Carnegie Hall in 1963, the last verse and chorus are all force and brutality and scorn, as if to disguise the singer’s disgust at his own tune. It’s horrifying and when the crowd applauds at the end of the song it feels all wrong, like a violation, as if the people in the audience think the song was congratulating them, as if when Dylan sings “You who philosophize disgrace” he’s talking about someone else. On Highway 61 all those years later, when that self-congratulation had become its own form of discourse, when in universities and journalism people were bullied out of the public square so that others could proclaim their own purity, there was no-one else. There was no way out of the song.

I think Marcus is right to imply Dylan is instinctively at odds with impervious, all-knowing ideologues. Though Dylan’s years as a Christer complicates matters. (OTOH, that period surely provides more evidence of Dylan’s variousness.) Unlike impervs who treat any current event as confirmation of their received ideas, Dylan has tended not to reduce genuine shocks to shticks. In seasons when new horrors provide grist for always-already wisdom machines, Dylan is with those who sense it’s inhuman to resist dumb wonder. (“Am I an idiot?”) Surprise is your best teacher.

Marcus goes back to what Dylan wrote when he tried to wrap his mind around the assassination of Medgar Evers. “Only a Pawn in Their Game” wasn’t a “finger-pointing song”:

It was a structural analysis of the social mechanisms of southern racism that somehow felt personal, the act of a particular person who, confronted with a soul-chilling assassination, had actually sat down to think about it, and had come up with a point of view that wasn’t entirely obvious.

Marcus doesn’t overpraise “Only a Pawn in their Game.” (“It’s not much of a song.”) When it comes to facts of the case and the killer’s motivation, Dylan was off. Medgar Evers’ murderer wasn’t a “poor white” (per “Pawn”) but a rich brazen monster of self-regard. Yet Marcus sees why the song rang true in its time.[4] “You could sense someone looking, putting himself in the place of someone else, seeing what that imaginary person would have seen, and seeing what they didn’t.”

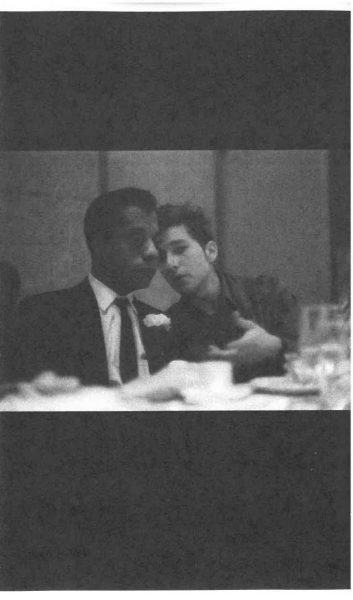

Dylan’s stretches are worthy of James Baldwin’s, earning the photo of the duo that gives Folk Music its frontispiece.

Marcus’s return to Dylan’s “Pawn’s” view – “From the poverty shacks, he looks from the cracks to the tracks” – reminded me of a moment when Baldwin entered a small-town southern restaurant through the “wrong door”:

“What you want, boy? What you want in here?” And then, a decontaminating gesture, “Right around there, boy. Right around there.” I had no idea what [the waitress] was talking about. I backed out the door. “Right around there, boy,” said a voice behind me. A white man appeared out of nowhere, on the sidewalk which had been empty not more than a second before. I stared at him blankly. He watched me steadily, with a kind of suspended menace…He had pointed to a door, and I knew immediately that he was pointing to the colored entrance. And this was a dreadful moment – as brief as lightning, and far more illuminating. I realized that this man thought he was being kind.

“Amidst terror, James Baldwin takes a feeling from the inside.” To quote a critic out to evoke how Baldwin caught the combined sense of power and inner, moral self-approval in the white man who showed him “the right way.” That critic was Benjamin DeMott who rose up for Baldwin’s peaks even as he spoke to the price of spokesmanship in a way that seems on point when it comes to Dylan’s own quandaries about “protest music” in the Sixties.[5]

I’m leery about bringing my dad to Marcus’s party, but maybe the author would give me dispensation since he brings up his own father in a passage that seems to be at the heart of the book’s…reckoning with race. In his chapter on “Desolation Row,” Marcus moves from conjuring up the possibility Dylan’s forbears might’ve witnessed those Duluth lynchings to revealing his own father nearly hung out with a lynch mob in California (after he got an invite from his parents to join a crowd that would break into a jail in order to hang two prisoners who’d been accused of kidnapping and murdering a widely beloved scion of a prominent Jewish family in San Jose).

Marcus seems to be musing around in this chapter on “Desolation Row,” but then he bears down as he thinks through his own familial legacy:

A lynching was entertainment, spectacle, even sport. It as also, like the Irish and then Jews putting on blackface until, in the words of Michael Rogin, they could be washed white, a ritual of Americanism, an exercise in civil loyalty, civic justice, and community solidarity. It wasn’t something a respectable businessman like my grandfather, or my grandmother, his business partner could afford to avoid…

Marcus comes back around from his own family history to Dylan’s notes of a native son—to the root of the historical sense that enabled Dylan to make his audience feel this nation’s touches of evil. (Not that Dylan didn’t choose sometimes to eat that country pie and remember to forget.)

Marcus’ daring readiness to go to the end of his own familial rope (and Dylan’s) shamed me. Reading about Marcus’s past served as a reminder of my avoidant refusal to, ah, do the work. (Please don’t let me be misunderstood. I’m not angling for careers open to anti-racist talents.) I’ve know forever that I carry the name of a Southerner who got shot in the ass at Pickett’s charge. (At least he was heading in the right direction?) But I’ve never really dug into my family’s Southern side. I’ve preferred to carry on thinking of myself as related vaguely to Emerson and some Puritan governor. Not that the North side of my fam has been all New England. My father grew up on Long Island. (There’s a DeMott Avenue out there somewhere.) That’s one reason I recently got enrapt in the opening of Walt Whitman’s Specimen Days, where he evokes his Long Island childhood—between orchards and the sea—along with teenage revels on vibrant streets of young Brooklyn. (My mom’s borough.) Whitman’s wonderful memoir is full of undeniable Americana. (Kerouac loved it.) Who could resist Whitman’s spunky great grandmother “who smoked tobacco,” rode like a man, “managing a most vicious horse”? But I read a little too fast. Skipping around in search of graces, I missed something that darkens all of Walt’s uncloudy days in the country and the city. It’s there in his friend John Burrough’s notes on the Whitman family and homestead, which Whitman quotes in Specimen Days. That’s where I learned about his great grandmother. And I was all in as she “went forth every day over her farmlands” until it turned out she was “directing the labor of her slaves.” [Emp. Supp.] Whitman wasn’t a cover-up artist. His friend Burroughs spoke of the true North:

The existence of slavery in New York at that time, and the possession by the family of some twelve or fifteen slaves, house and field servants, gave things quite a patriarchal look. The very young darkies could be seen, a swarm of them, toward sundown, in the kitchen, squatted in a circle on the floor, eating their supper of Indian pudding and milk.

There’s no direction home to a clean American past. Marcus has grasped that lesson. It’s one big takeaway from Folk Music. I’m sure you’ll find plenty more if you take his trip into Dylan’s imagination.

Notes

[1] To borrow Norman Mailer’s characterization of Henry Cabot Lodge (…III? or IV?). Though there were surely moral equivalents of Lodge among righteous leftists in the Village.

[2] I linked Dylan’s crossover move with “Near Andersonville”—Winslow Homer’s painting of an African-American slave woman trying to think her way out of danger—in the introduction to a First of the Year volume.

[3] Nothing New Under the Sun – First of the Month

[4] I bet it was Dylan’s drive to get inside the mind of murderer—”the hoofbeats pound in his brain”—that came through to me as an eight year old, not his class analysis.

[5] “Pity spokesman: their lot is hard. The movement of their ideas is looked at differently, studied for clues and confirmations, seems unindividual – less a result of personal growth than of cultural upsurge.”

DeMott spoke to a problem that Dylan finessed since he was able to slip in and out of “The Sixties” in a way that Baldwin couldn’t:

To function as a voice of outrage month after month for a decade and more strains heart and mind, and rhetoric as well: the consequence is a writing style ever on the edge of being winded by too many summonses to intensity.