Pride will vanish and glory will rot/

But virtue lives and cannot be forgot

Peter Wood’s amazingly graceful little book, Near Andersonville, tells how a Winslow Homer painting of an African American slave woman was lost to history and then found. In an act of imagination that’s worthy of the painter’s, Wood gently brings home the undiminished power — and deep relevance to our own time — of Homer’s way of seeing his black subject from within.

Near Andersonville, Newark Museum of Art

His book is something like a peculiarly American equivalent to T.J. Clark’s time-drenched Courbet book, Image of the People. Clark brought readers near to the absolute bourgeois contempt for the “mudsill” subjects of Courbet’s paintings and everyday people who scuffled into the Paris Salon to see this revolutionary art. While America’s urbane money-men may never have been so put out by true images of “the people,” Peter Wood’s will to bring race and class and “Winslow Homer’s civil war” into this and other Homer pictures has gotten under the…skin of reviewers in elite journals ranging from New Criterion to New York Review of Books. First put out a Call for reflections on Near Andersonville months before Christopher Benfy dismissed it in the March 24 NYRB. But Benfy’s attack has amped up the need to make a case for the book and for the strong black woman from rural Georgia who stands at the center of Homer’s painting, trying to think her way out of danger. Though, as Wood suggests in his final passage, “the woman in the sunlight” makes a fine argument for herself (and Homer).

During the past half a century, she has traveled little from her museum home in Newark, but over the years she has appeared on the cover of several book and magazines. She continues to have a small circle of admirers and a wide array of acquaintances. Interested people of all ages look in on her regularly in the spacious building on Washington Street. And every week, busloads of local school children gather around to ask respectful questions about her experiences, her feelings, and her point of view, I urge you to pay her a visit.

The following First forum on Near Andersonville starts with a short take by Amiri Baraka, who went back to live in his hometown of Newark around the time Homer’s painting was donated to the city’s museum. B.D.

A View from the Ark

By Amiri Baraka

Near Andersonville

is a deeply moving, deeply intelligent book. It illuminates the political and social life and attendant aesthetic trend during the civil war…19th century. An important work.

Return of the Repressed

By David Waldstreicher

What’s at stake in Winslow Homer that a veteran historian of the colonial south and slavery would shift gears and devote decades to studying the canvases of a Gilded Age Yankee?

Peter Wood knows something. He knows how much of our past has been rendered invisible by snowblinded cultural arbiters like Roger Kimball, who has made an attack on a 1981 article by Wood a centerpiece of a screed about how political correctness “savages” art. Peter Wood also knows how we forget. He begins his book by telling us exactly how the family that owned Near Andersonville did not actively remember why their old aunt had this painting of a strong, sensitive freedwoman standing at a planked crossroads with Confederate troops in the distance. They could not see it as the trophy of a committed activist, or express the buried knowledge. By showing us what was not seen, and then what was seen, and then what we might or ought to see, he shows us why art history is still called by that old fashioned name.

Jesse Lemisch wrote a brief essay once called “Who Will Write a Left History of Art while we are Putting our Balls on the Line?” He drew a line between those who would judge everything by its immediate political effectiveness – the kind of thing he had been and is still accused of – and the necessity of thinking long term, of writing that history of art, of having faith that such quixotic projects contribute, in their way, to our liberation from the very ways of seeing that such a project must carefully chronicle. Peter Wood’s elegant little book dances along that line, reminding us to take out revelations and inspirations in the struggle against racism where we find them: in the attic, in the museum, wherever. There are radicals crouching in that woodwork.

Winslow Homer’s vision was less white than some of his contemporaries. Much less white than their children’s. I read Homer’s title, and Wood’s, as a parable of why we can’t let the Civil War just go away: why we are seeing Confederate balls in Charleston and underground railroad remembrances this February. Talking about the Civil War is one way we talk about race in this country. Talking about the Civil War is one way we try not to talk about race in this country. Near Andersonville – near the horror of death by dysentery and minie balls – lies the story of what lengths we will go to deny what is always right in front of us.

Arrested Development

By Wesley Brown

When there is any mention of the American Civil War, it is likely to, immediately conjure up images of the pitched battles between Union and Confederate armies and the carnage that followed. This has been the case, for the most part, in the visual record of the War represented in photographs, paintings and films. What is startling about Winslow Homer’s (1865-66) painting, Near Andersonville, examined in Peter H. Wood’s illuminating book of the same name, is Homer’s conscious choice to go against convention, pushing the soldiers in the field of battle to the periphery of the canvas and bringing into the foreground the figure of a black woman standing in front of a cabin. The woman is looking off into the distance. But it’s unclear whether she is directing her attention to the Union soldiers who have been taken prisoners by Confederate troops or to something beyond the scene depicted in the painting. The woman’s gaze seems to be as much inward-looking as outward, causing the viewer to wonder what she is thinking, as she stands at the threshold of the cabin with a boarded pathway in front of her, leading in opposite directions. Could she be thinking about her inability to tell the difference between the Union blue and the Confederate gray, which Homer has made indistinguishable? Of course, we don’t know. But Winslow Homer has made it apparent that there is much on this black woman’s mind that few have taken notice of. However, he has taken notice by bringing her front and center and doing what Faulkner said is the aim of every artist: “to arrest motion, which is life, by artificial means and hold it fixed so that a hundred years later, when a stranger looks at it, it moves again since it is life.”

Reparations

By Robert Hullot-Kentor

A Note on the New York Review of Book’s article on Near Andersonville.

I read the review of Wood a month ago, Peter Wood’s book the month before. I probably misremember much of them. But if you and I were having lunch, Ben, what I’d want to say from my memories of both, without notes to double back and check, is that the reviewer didn’t catch what goes on in that little book. No doubt the reviewer is right that in some regards Wood’s presentation of the painting is skewed. It’s true, for instance, that Winslow Homer’s work is not at all allegorical in the way Wood asserts. But, what impressed me in Wood’s book was that — where it wasn’t true in its claims about the central figure’s pregnancy, her standing in for the biblical Hagar, and so on — the book all the same turned out true; what isn’t there, in the painting, what doesn’t meet the eye, is all the same directly in front of the eyes. Even the pregnancy that isn’t there, as the reviewer rightly points out, is right there under her hands on her smock. Wood got it across in a way I don’t think I’ve seen before – by its straining frustration in the face of all that isn’t seen, isn’t recognized, these many years later, which add up to not even one day later, to what’s still on every African American face. If the painting is not allegorical, there are allegorical eyes, Wood’s for instance. The puzzle of that little book is something like thinking about Picasso’s Guernica, which is compositionally a mediocre to worse painting, but all the same reaps fresh scalp from each and every next viewer. The painting is true by way of overstatement, desperate overstatement, by bad composition, by pure horrific, and even pure ridiculous KA-POW — and who ever got any truth across except that way? The correlative, I’m saying, with Wood, just to hammer it down, is how what is overstated, far-fetched and untrue in his study, all the same comes true in the whole of Wood’s book, through its tone, its own devoted, meticulous research, its distortions shaped by an antagonism to distortion, what the book and its labor wish for, what the book can’t let go of, and what it’s really about, all the saying of which would be meaningless if the book didn’t genuinely touch on something in Winslow Homer’s Near Andersonville that another touch, the professional art historian’s touch of his reviewer, would have failed altogether to sense and carry off. And, in Wood’s book, the attention he gives to that one piece of straw at the foot of the central figure: I never would have seen it; it is anything but an allegorical piece of straw, but all the same, it is located in that close sense we often have in Winslow Homer of where something might be carried next, whether by the wind, or a boat, or a gesture, or by history’s next moment; that piece of straw in Near Andersonville is another way of saying what’s at stake, and, when I think of it, it still makes me hold my breath. And why, I’d like to know, if the painting is so indifferent in the whole of Winslow Homer’s work — as the reviewer writes—would the review print it dead center in the article like that, where one can’t stop looking at it, not least of all because of how Peter Wood has helped us see it? The reviewer owed Peter Wood better, which doesn’t begin to say what history owes better to itself.

Near Deferral

By W.T. Lhamon Jr.

The contrast between the plain brown composition and its topic is striking. Emerging through its muted shades of everydayness is a complex awareness of deferred promise. Captured liberators are small in the distance while upfront an individual slave locates herself half lighted, half shadowed. The topic is the dawning of meaning behind enemy lines, squared: the woman is coming to understanding and so is the painter. He paints what he cannot have seen. Embedded as he was in the Union Army, Homer could not have gone beyond the slave cabins on a plantation to look back at captured Union soldiers past a reticent and thoughtful slave woman at her doorway contemplating the defeat of her potential liberators. The impossible view emphasizes the painter’s learning along with his subject’s. It was not given them. They had to make it.

Winslow Homer painted the dawning of inclusion before it could or can be real. The war evolved to be partly about inclusion and exclusion, fulfilling and denying the franchise. And this woman seems to be considering its possibility for her. Even now, a century and a half later, the franchise remains incomplete. Full inclusion has not yet occurred, but Homer finished his painting eighteen months after its scene, when the facts had improved for people like this slave and for her sympathizers. Emancipation had been proclaimed and enforced; inclusion was communicable. The history of the painting’s migration out of Georgia to New Jersey, its century of display in the home of northerners with abolitionist sympathy, that family’s forgetting what it had, the discovery of its commercial importance by accident, its neglect by art historians, the way its significance is still being demeaned by such reviews as Christopher Benfey’s in the New York Review, 24 March 2011 – all these are important for the deferral that is the painting’s whole meaning. This meaning coded in the painting is taking a long time to emerge.

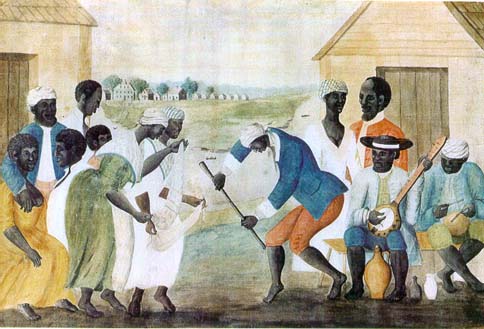

“The Old Plantation”

Deferred inclusion has been an issue Peter Wood’s investigation of black portraiture approaches throughout his career. His best known book, Black Majority: Negroes in Colonial South Carolina from 1670 through the Stono Rebellion (Knopf, 1974) uses no evidence after 1739, when the Stono violence erupted. But he put on his cover a naive painting – quite famous, often reproduced, almost never analyzed – that hangs today in Williamsburg, unfortunately titled, The Old Plantation. It is a small but tremendous document that foregrounds dancing South Carolina slaves and shrinks behind them the big house that they otherwise serve. Wood doubtless chose this image because it is a very rare, probably the only, early American painting that pictures blacks positively and charismatically, if mysteriously, rather than abject or debased. The problem is that watermarks on its paper prove that the painting dates to after 1770. It illustrates celebrations after Wood’s period. But the painting anticipates all the issues that Wood raises now in Near Andersonville. It does so from the point of view of a slave-holding Southerner’s emerging attraction to blackness, rather than the maverick self-education of a northerner with abolitionist conviction who painted the later picture.

Although he used it, Wood did not comment on The Old Plantation. He missed the chance to analyze its relations. His tight focus now on the meaning of Near Andersonville can only partially compensate because the distance that the earlier painting’s sympathy must cross is even wider and deeper than the gulf crossed in 1865-66. And the later woman in the doorway, imagined near the end of the war to free her, no matter how profound her realizations, is not as complex as the relationships among all the blacks in the earlier painting and the way they display themselves to the peeking white painter who has crossed out beyond their quarters to view them, just as Homer later imagined himself out there in the embattled south, near the attacked prison painting the dawning of hopes doomed to endless deferral. Everydayness wins.

Steal Away

By Lawrence Goodwyn

To establish a context for readers, it is useful for me to confess that I have a serious race problem. But, dear reader, do not expect me to be very topical or you will miss out on the nature of my problem and pass serenely over the dimensions of my malfunction.

I have had my race problem for a very long time and – since I am now well along in my 83rd year – its enduring nature has long since acquired, for me at least, impressive status as a problem. The malfunction dates at least from l954 when the Supreme Court alerted people like me to the fact that the Jim Crow realities defining the nation’s public schools were inherently destructive to the self-esteem of all children of color. At the time, in my provincial innocence Jim Crow laws seemed merely an insane intrusion into daily life. The dispatch of Jim Crow “with all deliberate speed” now seemed quite timely. Meamwhile, the emotional bludgeoning of young African Americans has continued through the years in our schools, even as the era of shouted sloganeering gave way to conversational circumlocutions or telling silences.

If all this sounds like the rhetorical approach of a policy wonk winding up to make a pitch for some new social adventure, you may bank on the fact I am not going there. Serious democratic educational beachheads have been established in some locales, thanks to the Wendy Kopps of this world. Despite such vital breakthroughs we do not as a citizenry yet understand the essential components. Therefore, the necessary know how and corresponding cultural will is simply not in place. Too much residual white suprenacy throughout the land. At bottom, white Americans do not understand the specifics of the educational crisis at the elementary and secondary level and therefore cannot distinguish between sundry approaches that have serious traction and those with political or racial clout that provide merely the appearance of traction. Because we cannot see the distinctions, we literally cannot perceive quality even when it is in front of our eyes.

All of which brings me to Peter Woods’ revelatory book about Winslow’s Homer’s binoculars. Woods wants to show us how acutely Homer saw the slave South at the heart of the constitutional crisis that generated the Civil War and Reconstruction.

It think it would constitute a gliby primitive mistake to see Homer’s observational lenses not only as powerful, but belatedly recognized as powerful only because of Wood’s own quiet and graciously effective literary skill. Such a ”bridge too far” double play would offer convenient and much needed protection for the embattled democratic reputation of what threatens to become a banker-dominated, corporate-infested Republic. Peter Wood clearly has no intention of offering such a defense and Homer manifestly does not need or covet it. What these two Americans, a painter from Massachusetts and a historian from St.Louis, have in common, is that they travel easily within our democratic heritage. Homer’s cumulative American portrait speaks for itself. Wood’s path-breaking colonial history of South Carolina is one of the great books of the American experience. My favorite Chapter in Black Majority focuses on the “Runaways.” It is entitled: “The Slaves Who Stole Themselves.”

Let the young woman at the cabin door have her uncontested place in the sunlight. She has been there a very long time.

From March, 2011