Part two of an essay that began here.

L.A. Fire & Ice

Bruce Springsteen’s look back in Born to Run on “L.A. burning” reminded me of Richard Meltzer’s felt statement in the moment (which belongs in any canon of American protest writings). Meltzer realized “Black people don’t need my whining.” He was writing “for white people, obviously” and the raging epiphanies in “L.A., May 4” should still speak to his target audience …

I’ve lived in this idiot, airless town for 17 years and have never for a moment felt the slightest stirring of anything you might call civic pride…Not until, that is, the second day of the uprising, the “riot,” when suddenly like lightening it hit me: this was its finest hour! The heroes, the martyrs, trashing and torching the town!—taking their wrath beyond the ghetto, from Bullock’s Wilshire to the Farmer’s Market to Beverly Center to Frederick’s of fucking Hollywood, saying loudly, clearly not even just No (which itself would have been a monumental achievement), but a very unambiguous Something: the system doesn’t work…even the system of oppression doesn’t—can’t—always do it. Against super-daunting odds: their finest hour. If I had photos of every black and Latino martyr killed by cops, by feds, I would put ‘em on a T-shirt and wear it every day of my life.

Meltzer was one of the original rock writers—see his early Aesthetics of Rock and later A Whore Just Like the Rest: The Music Writings of Richard Meltzer, where you can find “L.A., May 4”—and his clarity about black people’s place in American musicking amped up his polemic:

We’re talking about people who with whips and chains to their back, guns to their head, have built this country, clothed and fed it, cleaned its toilets, raised its children, suffered its directed sadism and degradation, given it the only indigenous (post-pre-Columbian) arts it’s ever had, jazz and rock (only to see others reap the lion’s share of profits and praise), bestowed upon every sport they’ve touched, the essence-flaunting power chord and grace note, its utter crowning Americaness (ditto), given us “hot,” “cool,” taught us more about “style” than a billion Parisians, been the republic’s moral barometer through all weathers, all seasons, its only true pillar of even conventional virtue…these are generous people, Jack!

Meltzer blew back against the showy befuddlement of pundits:

“Violence against your own community”? When there’s no way out! no way out!, what the bloody deuce do you do? Haven’t you ever, when emotionally cornered, dug your nails into your wrist, slapped yourself in the ear, smashed a favorite cup against the wall, lashed out at those you truly love? Y’know: spontaneously done “something self-destructive”? Never, you say? Well, you’re lying. (Or have so submerged the role of feeling in your life that you’re ice on ice—in a vault—at the bottom of the sea.)

Meltzer soured on L.A. long before ‘92. His book of reportage, L.A. Is the Capital of Kansas (1988) lays down lessons in “post-New York living” (by a “goddamn writer in a town where nobody reads”) that tend to be yuk-y and self-mocking. Yet you can hear the righteous voice of “L.A., May 2” when he recalls giving a friend a tour of L.A. As they drove around on a breezy desert night after a hot day, Meltzer and his buddy who’d never visited the city took its emotional temperature:

We drove through cold silent this neighborhood, cold silent that; through cold silent theater districts and cold customerless all-night drive-throughs; past cold silent sleepytime sleepyheads in cold card-board boxes on cold cold skid row cement. We drove on, mostly in silence, until, feeling at last the emotional desert chill which is L.A.’s and L.A.’s alone, my companion had had enough. “God, who’d have thought the place could be so…forlorn?” He’s lucky we didn’t take the daytime tour of same!…

To Wit: for all of its swimming pools, “lifestyle” and jacarandas, L.A. can surely be a town without pity, a hot-cold bottomless misery pit, for the poor, the past-it, the unattractive and the merely unfashionable…and for absolutely anyone on any given day. In due time, in real time, the passing parade will pass HERE.

American Sublime

At the risk of fading out of history into nature (per Barthes’ critique of bourgie mythologies), I’m going to cut to a cold cold night from one of Born to Run’s road trips. Springsteen recalls how he ran into a vicious snowstorm crossing the western mountains: “the road disappeared before our eyes, there was so much snow it was impossible to tell the location of the highway’s shoulder.” Easterners, he writes, don’t really know from fearsome blizzards. A big snow storm in our neck of the country means a graceful winterlude—“dirty streets covered in virgin white”—and a freshened sense of dailiness—“something new might happen.” Out west, though, regeneration isn’t in Springsteen’s snowblinded sight. A blizzard comes down to confinement and “dread of a dark, covered world.” Springsteen muses how he’s felt that twice:

Once in Idaho, where it snowed circus clowns for seventy two hours, all power and light gone, eternal night and judgment day upon us. The other was that highway evening on the pass. There was too much quiet, too much weight, too few boundaries and no dimension. The world had been planed down to a snow-blind table you could easily slide off the edges of. It had been simplified into the passable and impassable. The early ocean mapmakers had it right: the world was flat and a wrong move to the left or right could bring you to the brink of the abyss, and beyond there be monsters.

Springsteen’s spooky highway eve sent me back to an eternal 3 A.M. in Michael Ventura’s novel, Night Time Losing Time (1989). A blizzard in the Texas panhandle has slowed down a trio of rock ‘n’ rollers even as it’s setting these characters in motion. The scene is narrated by Jesse Wales, a piano player who’s on his way to being a “living legend” (though he’s fated to be a local hero not a national star). He’s riding with Nadine, his mostly estranged wife who’s the girl singer in his group, and his best buddy/band mate Danny. Jesse is taking in the “white darkness” as the snow glows under a nearly full moon when…

Danny said, “Cut the lights,” and I did.

Danny was right – under this moon we could see fine without the lights. It became more like floating than driving. The road rose and dipped. On the rises you saw miles of white snow-light. In the dips it was like sliding into shadow-ponds—I’d ease off the gas and feel my engine cut just enough so my Chevy seemed to be finding its own way down, while I steered dead in the center of the road—there were no shoulders, and with the snow you couldn’t be sure what was and wasn’t road around the edges. It was three in the morning, as usual, and there was nothing on the road, no tracks but what we left behind us…

Any musician can tell you sounds change in different lights. In that snow-light, even under the drone of the engine. I could hear Nadine’s breathing in the back seat soft and clear as a drummer’s brushes on the cymbals. She’d been curled asleep back there since Idalou.

The road rose and dipped in the silvery dark. There were cottonwoods in the dips now, so I knew the Red River was close…

We saw it on the next rise. The snow in the riverbed glared back at the moon. I slowed to almost nothing because there’d be ice on the bridge.

“Apocalypse ain’t so bad.” Danny said, out of nowhere, as was his way…

I stopped the car in the middle of the bridge. It was like you could hear the light, a note held forever, so low and so high at the same time, so black and so white. It was like the moon and the earth had traded places.

“Should we wake Nadine?” I said.

“That’s an interesting dilemma. I was just weighing it myself. Cause, like, is she better off seeing this, or letting it pour into her sleep?”

We sat still while the car got colder and the light got louder.

“Oh Lord!” Nadine whispered. She’d woken soundlessly. She leaned her head over the front seat and shook her hair out. Straight and fine, it swayed near me, and I could smell how clean it was.

“”Let’s just stay right here,” she said. “I mean, let’s settle.

As they watch from the bridge, two dark horses walk from beneath it, heading up the river bed. Nadine who wants to have a child with Jesse wishes there were three. (But the scene is still full of portents for her; she’ll soon become pregnant and born again.) Danny starts to sing “Red River Valley” in his “sweet throat-warbly voice” (like Jimmy Dale Gilmore’s?): “It was unbelievable that a man could sound so sweet and still sound like a man…but somewhere in that unbelievable sweetness something was being squeezed, twisted even, and was letting you know.” Danny lets the song “just hang after three lines.” He ends up staring at the horses wondering where the other two are: “There are supposed to be four, doesn’t it say?”

Night Time Losing Time will tell what happens to these “apocalypse people” and their friends, families, lovers/gurus. Ventura’s song for them pays tribute to a remnant of a remnant—that Southwestern cohort who keep roots music alive in places like Austin and New Orleans.

Middle Distance

Night Time Losing Time’s chapters often start with epigrams lifted from lyrics of rock ‘n’ roll standards (or blues and country songs). Ventura has Austin’s real players turn out for a funeral in Lubbock (Buddy Holly’s hometown), but only one actual musician has a role in the novel—the late Stevie Vaughan. Ventura captures the way Vaughan looked and sounded “before he put the Ray between his names and started becoming a star.” (Ventura’s imaging of this “skinny kid” brings home how Vaughan was once a brother under the skin of young Springsteen:

Back when [Vaughn] had no rep outside of Austin, no money, nothing to fall back on but a drummer, a bass-man, and those beat-up guitars he’d play… [W]ith his mashed nose and that look that managed to be real innocent and a little mean all at once, his arms like a boxer’s and his cocky beret (it was always berets back then, not those flashy hats he wore later), and that big peacock tattoo on his chest that his flashy clothes conceal now.

After sitting in on piano with Vaughan in an Austin club (and slipping a dangerous, affronted husband), Ventura’s venturer retreats to the parking lot where he meets the woman who will become his next wife. She likes to hang outside after work, smoking a joint and listening to young Stevie inside the club: “[H]e amplified that building into a brick jukebox, slightly muffled, but the guitar lines strong and clear, and it made the parking lot, the whole deserted street come darkly alive.”

That guitar sound and its reception instantiates what George Trow called “the disappearing middle distance”—his phrase for the private-public nexus of genuine cultural transmission he thought was getting trashed in America due to tv’s hegemony. Musicking in clubs and small theaters is a middle distance thing. Stadiums, by contrast, are where good grooves go to die in celeb-mongering grids.[3]

Springsteen may have become an echt arena rocker but he was once a middle distance guy who did a lot of his training in the Village during the 60s. That’s where/when he got up close to guitar masters on the come—such as Neil Young with his “signature black Gibson plugged into a tiny fender amp, blowing out the walls of the Bitter End”—but he learned from less famous players too. He recalls one Village cat who “played Jeff Beck as good as Beck”:

Steve [Van Zandt] and I made the bus trip on many afternoons just to sit there slack-jawed at [Teddy Speleos’s] sound, technique and nonchalance. He was just a teenager like us but became a huge hero to Steve and me. We were never going to get within fifty feet of Jeff Beck, but this kid, there he was, inches away from our faces, and like the monkeys in 2001, we sat there primitively hypnotized by style, substance and flash we could not comprehend. Steve and I rushed home to our guitars, hoping to catch some of the richness of distortion, the molasses thickness of tone Teddy was squeezing out of his Telecaster. Unfortunately we’d end up with a howling, screaming, murdering, chain-saw massacre of sound squealing up out of the basement from our Teles. How did he do it? He KNEW how, THAT’s how.

Rock ‘n’ rollers are bearers of aural knowledge on Ventura’s turf, but they’re also into the mystic/cryptic. (“Night Time Losing Time”–Ventura’s antithesis to Daylight Saving Time–avers to his rockin’ apocalypse peeps’ openness to extremes). When it comes to music qua music, though, Ventura’s version of the tradition is more delimited than Springsteen’s. Ventura’s main man (and alter-ego), Jesse, hates how his music becomes a beggar in New York and Los Angeles where it must “fit into their mainstream, their ‘new wave’ or whatever.” He insists New York and L.A. are far from rock ‘n’ roll’s ground zero:

Texas, Louisiana, Mississippi, Tennessee—that’s where this music comes from. And it doesn’t have to go anywhere, it’s always been home. It comes out of the way people here live and it goes back into their lives, back and forth, in the clubs every night. It changes because they change, and they change because it changes.

The alt night life tradition Ventura’s novel upholds is bigger than any individual star or style. Per Jesse’s rap on his gig at (the original) Tipitina’s in New Orleans, which is one of the book’s many mission statements: “I always knew, when I sat down at the piano stool, even before I hit the first key how strong or weak was the purpose calling me from the crowd…”

I didn’t count off, didn’t look around. I just hit the keys and let the band fall in. Sometimes you play piano from your fingers and sometimes you play from your shoulders, sometimes you play from your chest, sometimes from your knees. It was knees and elbows and shoulders that night, not like I was playing the piano but like I was moving the piano, pushing it up a hill toward a music that wasn’t mine, wasn’t anybody’s. That classic Professor Longhair left hand bottom line, which you practically had to do at Tipitina’s your first number of the night, but crashing some weird Monk-ish chords on top of it that woke that crowd up and made them turn their heads while I bent the melody of an old New Orleans rock hit…

…a Jerry Lee Lewis sweep up into the high notes, but ending the run on a chord that wasn’t supposed to be there, except it fit, sweet shit, it fit, like you can throw a square block of wood into a pond but you can’t tell from the splash that it’s square, the ripples from the splash come out round no matter the shape of what went down. That’s how I wanted those chords to fit into those blues…

I didn’t have to look down. I could feel the people dancing through my ass, the floor vibrating up into the piano bench.

Backdoors of Perception

Jesse’s faith in woke asses extends from the bandstand to the bedroom.

Oh I had to coax you, Nadine, for so long, for weeks, touching it now and again, lightly, till that night, Nade, when I was feeding on your pussy and turned you around and stuck my tongue in your butthole till your ass woke up and did its wanting all on its own. And for nights then that great ass became our baby, we goo-gooed over it and were proud of it and liked to see how it was doing, learning how ass-life is different from cunt-life. Inside cunt it’s like talking or dancing, inside ass it’s like falling. You can never get enough of cunt, cunt defies and defines all laws, two creatures occupying the same space together, matter/antimatter, you could explode. But with ass, you fall, fall together, falling through shit, connected but not in the same place, clasped but from separate worlds, falling end over end toward where, the black hole, you don’t know, end over end, squeeze of pain going in and then that lushness that does not end, not like the cunt that you can plumb the bottom of—“nobody’s ever been so deep inside me”—‘cause ass doesn’t stop until mouth and then there’s just air that’s not stopping, and the never-ending hole of it makes for movement not like cunt’s, a rhythm that’s a falling till, when you come, it’s like a parachute suddenly opening, it jerks both of you up hard, and in the aftermath of come you just kind of float dazed awhile. You don’t know where you’ve been. You do with cunt. You both went through cunt once, you lived it, you wanted to scream into its walls, you pushed against its side with your shoulders, with your feet you clawed it from the inside, you breathed it, you know. So no matter how many times you go there, you can’t know ass like you know cunt.

Night Time Losing Time synchs up acidic esoterica of the 60s with spirits invoked (or shunned) in down home roots music. That won’t seem too outlandish to heads who recall, say, how Mick Jagger nailed Robert Johnson songs (including “Me and the Devil”) in the trippy flic Performance. Not that Ventura’s journeys to the end of the night always make it. Yet even if you can’t get your mind around every rite of intensity, there are saving grace notes. Ventura isn’t too solemn about his faith in endarkement. He teases himself after one scene where Jesse gets shaken and stirred by a lover into hoodoo. She’s a rock journalist and on the way back from their psychosexual ritual in Mexico Jesse asks her: ”You’re a writer. You ever write about this stuff?” She responds, ”And have everybody think I’m silly? No, thank you.”

Ventura’s riskier acts may explain why Norman Mailer blurbed Night Time Losing Time. Minus hocus-pocus, I doubt Mailer would’ve proposed the book was the best novel ever written about American musicians. Though I’m sure he also went for Ventura’s more hardcore metaphors. (And this Maileresque little death—“I came like I was puking through my cock”—is to die for.)

My own favorite ride in the book is pretty far gone from Do-As-Thou-Wilt wilding. It comes near the end when Jesse’s ten years further up the road. He’s in a car with his son Jes, rolling through a thunderstorm. Dad has screwed up, getting angry and scaring his boy who’s closing down. But suddenly old Jesse starts feeling the storm, locking into a liminal state that’s linked with sex and rock ‘n’ roll in his mind:

I felt that storm through the vibrating steering wheel, loved the pounding drops on the hood, the watery hiss of the wheels, and felt approval in the storm, knew it pleased the storm to be driven through like this, and must have had some crazy grin on my face because when I Iooked over at Jes, again he was surprised, said, “What?”

“Isn’t this a great STORM!”

And I reached over and grabbed his hand and squeezed it hard. And he didn’t say anything but he laughed. We both did, and the storm laughed back at us, and I said, “hear that storm laughing man!”

And I prayed he’d remember this one day, he and his strange old man hurtling through the rain, laughing after a bad time. And that maybe he’d psych someday, sooner than I had, that the storm’s there for our elation as much as for the crops.

This re-reader was struck by the contrast between Ventura’s stretch goals in Night Time Losing Time and Springsteen’s relative restraint in Born to Run. It’s not that nothing’s sacred to Springsteen. He grew up Catholic like Ventura (and Kerouac) and God is real to him, but he’s not grabby about intimations from the Other Side. Course it may be more natural for him to break on through on stage than on the page. He’s surely a vector of high emotion in this recent live version of “Living Proof”, which he dedicates to his son Evan, whose birth inspired the song. (Per the first verse:

“Well now on a summer night in a dusky room

Come a little piece of the Lord’s undying light

Crying like he swallowed the fiery moon

In his mother’s arms it was all the beauty I could take

Like the missing words to some prayer that I could never make

In a world so hard and dirty so fouled and confused

Searching for a little bit of God’s mercy

I found living proof”)

Listen up for the strangled cry of wonder-love on the final chorus before the guitar army marches out.

Honky Tonk Heroes

In a chapter titled, “Losing My Religion,” Springsteen tells how he came to have his first drink when he was twenty-two. A buddy, Big Danny, knew Springsteen needed a lift so he made him belly up to a bar for a tequila. I’m reminded Jesse and that journo’s fictive ramble in Mexico was fueled by mescal and, along the way, muy macho Jesse takes the piss out of tequila:

Tequila’s mescal after mescal’s been pacified, distilled, numbed, spiffed enough to make it presentable in mixed company. They leave the worm at the bottom of the mescal bottle. Mescal thinks tequila is a joke.

Springsteen would agree tequila is a hoot, but it was good as gold to him.

….a small glass shot glass was slammed down in front of me filled with a golden liquid. Danny said, “Don’t sip it, don’t taste it, just swig it down in one quick gulp.” I did. No big deal. We did another. Slowly, something came over me; I was high for the first time. Another round and shortly I was having what felt like the finest evening of my young life. What had I been sweating and worrying about? All was good, wonderful even. The angels of mescal were circling around and informing my being…

Other angels appeared. The Shirelles hit the stage in the club, sounding and looking fine. And then Springsteen bumped into an old high school crush who was hot to flirt. They didn’t end up in bed and Springsteen wound up with a hangover but he was still juiced by his first night out with “his best friend, Jose Cuervo Gold”:

I’d shut down my loudmouthed, guilt-infested, self-doubting, flagellating inner voice for an evening. I found, unlike my father, I was generally a merry drinker simply prone to foolish behavior and occasional sexual misadventures, so from then on and for quite a while thereafter the mescal flowed…tequila.

Springsteen’s memories of pouring it all out mix up well with cheerier bits in the chapter, “Days of Beer and Daisies,” from Meltzer’s The Night (Alone)(1995). Meltzer relives his bar hops with rockwrite comrade Nick Tosches (“Mike Tonk”). It’s hard to choose among his tales of their pop-a-top life but here’s one for the road:

One night, for the fuck of it, we hit an East side biker bar with mixed drinks our goal. Beginning with Carstairs & tonics we moved on to sidecars and bourbon Manhattans, then ordered a single Zeus (vodka, Campari) and a blood & sand (gin, sloe gin, crushed ice). “How’s that again?” asked the tortured barman. (Luckily, that day, we’d torn pages from a mix guide at the Strand.) Lacking both essentials, he couldn’t make a 252 (151 rum, Wild Turkey 101), so we improvised a 240 (Seagram’s V.O., Christian Brothers brandy, Juan Valdez tequila, 80 each). We didn’t even ask for a Rasputin (vodka, clam juice, anchovy-stuffed black olive) but were on a collision course for applejack highballs when, at pool, I lost our last fiver to this old guy with one eye sewn shut. Hangovers no worse than usual.

Meltzer’s raps on bar folks’ talk hint why, ever since the 60s, his own voice has been as distinctive as any American writer’s. It all comes down to his ear:

Over to our right a dude in a frayed plaid trench coat makes lively small talk with a nimble buxom fortyish platinum blonde:

“Driving this morning was a bitch.”

“Watch you language, there are bitches present.” He lights her Lark.

“I’ll tell you one thing, at my age it’s better to pull over and screw the car.”

“And how old is that?”

“Fifty-eight in May.”

“Well, you’re getting there. In ten years you’ll be up at the speed of sex.”

“What’s that?”

“Sixty-eight. At sixty-nine you have to turn around.”

“I’ll take seventy-seven. “That’s eight more.”

“Depends on who gets eight.”

“You sure are one lazy s.o.b.”

“Ain’t it the truth.”

“Hey where do I leak it?”Barkeep directs her accordingly…

Meltzer makes his own case for the dive bar as middle distance place—“the antidote to TV heart-mind-soul control.” But he laments how TV came on strong: “Bar sets used to be on only for the World Series or something. Title fights. Events. But pro beach volleyball interviews? Reruns of Quincy?” (Jim Ed Brown—“a row of fools on a row of stools”—meet George W.S. Trow.)

And that was then, with everyone phoning it in now, common life in the lower-middle depths is ever more at risk of being screened out.

Meltzer’s Honky Tonk tales focus chiefly on his own changes. Alcohol helped get him loose (like Bruce). It eased his shyness around women: “Even minor doses have made my fool’s twaddle smoother, my pawings less awkward, my idiot heart-thump less conspicuously LOUD.” But his sex-playfulness “declined” over the years though “intake continued” leaving him to wonder where all the good times had gone and “what exactly do you do with all the rocket fueled idiot momentum, idiot frustration, idiot id.”

Land ‘o’ Crabs

Meltzer lets id all hang out in The Night (Alone) like his beat avatars, Jim Morrison, Mailer, Lenny Bruce, and Brando. In a nod to Last Tango in Paris, he calls himself a “good stickman,” but he also confesses to “days of doodle-doubt.” Organ music in The Night (Alone) underscores his ballsy impulse to expose all. Meltzer likes to play with names for his member AKA “unit,“ “item,” “dingo,” “wango,” “wanger,” “stalk,” “spud,” “salami,” “bo-log,” and “Nixon”!! (Code for Tricky Dick?)

Springsteen, OTOH, tends to keep his unit private in Born to Run, but he does go public with the cringey outcome of one Californication. When he headed back east after his second visit to Cali where he stayed with his parents and used the same facilities at their apartment: “all I left behind for my pops was a case of the crabs I picked up somewhere along the way.”

Meltzer topped that with a Cali crabs story in The Night (Alone)—one that’s marked by his sui generis mix of humor and horror (as well as his wit about form). He presents a Q&A devoted to a visit to L.A. in the 70s which led to a tame one-night stand and then an awesome one. The sex in round two was overwhelming and Meltzer goes into the meaty details of his “delirium” which “felt like love.” While his pre-coital convo with his new partner had been bland, intercourse had led to conjoint communing: “the things she was saying in bed, the fuck things were a lot more interesting, much more expressive and revealing of, y’know, someone I could actually, than anything she’d been saying otherwise.” After he “bursts in a heap between her legs,” he goes down on his new lover. There’s a taste that’s off (“like hairspray or Lysol”). And he realizes it must be residue from the anti-crab medicine he doused himself with earlier in the day after his nada hook-up the night before. He didn’t believe he had crabs but it seemed “wise, y’know ‘worldly’—the mature, responsible, so you don’t spread ‘em, if you got em.” The imagined Interviewer then sets up readers for Meltzer’s killjoy joke on himself.

Q: So meanwhile you’re eating her…

A: Right. Although the taste is like paint remover I plod along, just keep, try to avoid thinking about…Then I start wondering if it’s mutually unpleasant, ‘cause my beard possibly, hadn’t shaved, I hadn’t expected, so maybe, but she didn’t say, didn’t stop, she held my head down and went, “Oh God, oh God,” which seemed like approval. She came like a machine gun and I kept up, she came another couple times and then pushes me away. “Oh thank you,” and before I know it she has my dick, which by now is hard again—“Let me do you.” She starts sucking me, wet, deep, with real purpose, real, then she recoils in horror. Crab-knowledge, she’s quicker than I was at tasting, identifying – L.A. crab knowledge! – it’s there in her face. If I don’t have living parasites where her mouth and cunt just, she knows I have had, recently and who knows what else, and who else – I’m very tainted goods. From something to nothing in…

Lover’s Discourse

Springsteen recalls one who got away (“a lovely surfer girl, a drug-taking, hell-raising wild child who played by nobody’s rules”), but unrequited romantic passion is not a major theme in Born to Run. Springsteen doesn’t boast about being a Romeo, but his underlying certainty about his own attractiveness to women may have helped keep him going through ups and downs of his extended apprenticeship in the 60s and 70s.

Meltzer’s had his fun too. His move to L.A. facilitated his pursuit of “moisture” but his choice to throw in the towel on New York proved to be soul-making too (as he explained back in the 80s):

[Southern Cal] is, was, always will be the major leagues of sap/heat/sizzle, a league I’d probably have been “too smart’ to ever play in, to suit up for in smarty-pants New York. Having played, though, having let my heart and pecker supply me with a richly diversified experiential base, I’ve occasionally managed—here’s the socially redeeming part!—to turn critical sex-think corners that might’ve remained remote from me in Smart Town…

He talked straight about how he was done with “la vie hot nuts” talked up by He-Men like Henry Miller.

I’ve actually overcome certain long-held creepster orientations. I’m no longer especially youth-centric or meatocentric, for inst, preferring the company of womanpersons my own age. And dealing with them ultimately as womanperson qua person i.e. as the persons behind the meat, bodily occupying warm and bouncy carnal matter, who in the final analysis are essentially warm, bouncy persons. Y‘know not “objects.” For an ol piece of pigmeat I’ve come a long way.

Meltzer peaks as a writer when he confesses to needing one of those persons much worse than just bad. There’s a piece in L.A. Is the Capital of Kansas, “Silent Nite,” where he suffers like a prickly Proust waiting and waiting on an Angeleno Albertine who’s stood him up “once, twice, fifty times.” The b-side to that sequence might be this tune from The Night (Alone):

Duh da da da duh da da duh da da like you, duh da like you do, duh da da duh da. Duh da da da duh da da – NAME THIS TUNE – duh da da your name, du da so ashamed, duh da wasn’t you, wasn’t you, and then the chorus, YOU ARE, well it can’t be anything but: “You Are Everything” by the Stylistics. You are everything and EVERYTHING IS YOU. I used to sit and weep over that one, weep at the chord changes, weep at the sentiment, weep in goddam awe at the concept of YOU as essential principle, as the essential principle, every bit as basic as Thales’ water, Anaximenes’ air, Pythagoras’s number. I never bought the record or heard it on radio, only way, only time I ever caught it was off jukes in bars. I’d be hunched over a drink as it played, ruminating only occasionally over a specific you just past or present, an actual second person other, and depending on how much I’d already had, by song’s end I’d be either a blubbering, maudlin mess or sublimely maudlin…you had to be there to see it.

“The Night Has a Thousand Eyes”

Meltzer rates five version of this jazz standard in The Night (Alone), starting with Coltrane’s (“there really are no bad versions of this tune”). His list got me thinking on how many times young Springsteen came at the, ah, issue. There’s “Spirit in the Night,” “Prove it all Night,” “Something in the Night,” “City of Night,” “Night,” “Because the Night,” “Bring on the Night,” “Restless Nights.” (And “Darkness on the Edge of Town” isn’t exactly an outlier…)

T for Texas

One of the heaviest nights in Springsteen’s life occurred in the early 80s when he was on what was supposed to be a recreative cross-country road-trip. Driving through a town in Texas and watching a band playing at a country fair, Springsteen experienced a wave of despair. A crisis that would lead to a 30 year therapeutic movement of mind which is ongoing. (Springsteen’s most daring personal revelations in Born to Run are about that process which has involved docs and meds.) Springsteen can’t say why but…

It’s here in this little river town, that my life as an observer, an actor staying cautiously and safely out of the emotional fray, away from the consequences, the normal messiness of living and loving, reveals its cost to me. At thirty-two, in the middle of the USA, on this night, I’ve just exceeded the once-surefire soul-and-mind-numbing power of my rock ‘n’ roll meds.

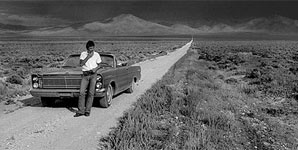

There’s something about Texas. Ventura’s all in obviously. And Meltzer’s felt it too. Back in the day, he honored his Beat heroes with a solo drive from Providence to L.A. (though the myth of America was largely lost on him). He dug autumn in P.A. and random autonomist moments along the way when he sensed he was outside the sway of metro twits/sophisticates. But his favorite stretch on the road was in Texas where he seems to have felt the force that impelled Springsteen to get real:

[H]ere’s a firm, sweaty handshake for West Texas qua PLACE. The no-pretense, no-alibi turf of not necessarily “tough guys,” um, let us say “outlaws,” no-home-on-earth “misfits,” “desperados.” Maverick: a motherless calf. “Mavericks” too. Such folk are eminently credible now/then. And the land. NO comfort from the land (only whiskey, orgaz, beer, the Cowboys or Oilers on Sundays).

But what about music? On his night of nights, Springsteen recalls putting on his Texas tape with Bobby Fuller’s “I Fought the Law.” But there was this other song I heard one time…

Bob Dylan’s “Brownsville Girl” may be the perfect soundtrack for all these Texas trips. Dylan’s epic road song affirmed his faith in Beat paths and mythic American mavericks.

“How far are y’all going,” Ruby asked us with a sigh

“We’re going all the way ’til the wheels fall off and burn

‘Til the sun peels the paint and the seat covers fade and the water moccasin dies”

Ruby just smiled and said, “ah, you know some babies never learn”

Dylan was one of those babies born to go with their imaginations. You can tell he has a deep tenderness for his younger–Bobby-the-Kid, wunderkind–self, but the brilliance of “Brownsville Girl” is how he manages to get fresh about feeling old hat. Dylan teasingly invokes his own persona—“the only thing we knew for sure about Henry Porter was that his name wasn’t really Henry Porter”—as well as episodes in his private and public life (“we got him cornered in the churchyard”). Dylan’s always been one of the traveling kind—“I didn’t know whether to duck or run, so I ran”—but by the mid-80s (as he’d write in Chronicles) his old songs were weighing him down like a “package of heavy rotting meat.” He felt like “an old actor fumbling in garbage cans outside the theater of past triumphs.” In the time-drenched “Brownsville Girl,” Gregory Peck’s transformation from young gun/star (in the late 40s flic The Gunfighter) to stiff icon stands in for the almost unfathomable mutation in Dylan’s pop persona. After years of never being boring, Dylan seemed to be presiding over a descent into blankness: “I don’t know what’s it about. But I’ll go see him in anything. I’ll stand in line.” But Dylan wasn’t just taking up space in “Brownsville Girl.” It’s some of the best acting he’s ever done on record. (It’s surely the finest white rap track.)

Dylan recently cited “Brownsville Girl” when he was asked if there were any songs of his he thought deserved more noticings. Ventura may have picked up on it on early. Jesse almost gets religion in the “mean-eyed border town” of Brownsville and in the novel’s final scene he runs into the living image of his younger self in a fast-food joint:

When he finished eating he walked with just my slouchy swagger out into the parking lot. Then spun, like a gunfighter in a Western, to stare straight into my eyes through the window. He had known every instant that I was watching him, sure. He was deciding what to do about it. I knew that this body had recognized me, like mine had him, but he hadn’t realized…I wondered if he’d remember me. I called after in my head. Remember, remember! Maybe, just maybe in thirty years he’d look in a mirror and all of a sudden really remember.

Dylan serves as one of Ventura’s/Jesse’s avatars and I bet “Brownsville Girl’s” “he-was-me” flashbacks were in the equation at Night’s end when Jesse met his lovable young double who moved like a gunfighter.

Generational Animus & Class Struggle

Springsteen has dubbed Dylan “The Father of My Country.” In Born to Run, he recalls how they once had a private exchange after Springsteen had sung “The Times They Are A-Changin’” at a ceremony honoring Dylan.

We were alone together for a brief moment walking down a back stairwell when he thanked me for being there and said, “If there’s anything I can ever do for you…” I thought, “Are you kidding me?” and answered, “It’s already been done.”

On the real side, though, Dylan might owe Springsteen one. Back in the mid-80s Dylan improvised a hard goof on Springsteen’s Jersey persona and familiars (Thunder Road, “that old abandoned factory,” etc.). Dylan recorded “Tweeter and the Monkey-man”—the title tweaks “Tenth Avenue Freeze-out’s” “Scooter and the Big Man”—with The Traveling Wilburys. Springsteen can laugh at himself so he probably dug this fruit of Dylan’s Old Adam. Though he may also have realized there was a truth attack inside Dylan’s jape. When Tweeter turns out to be trans—“I knew him before he became a Jersey girl”—the below-the-belt punchline amounted to a sly comment on Springsteen’s image when he got really big in the mid-80s. As Springsteen himself notes, pics of him with bandana and pumped muscles from the “Born in the USA” era seem in retrospect like an extreme makeover: “I look simply…gay. I probably would’ve fit right in down on Christopher Street in any one of the leather bars.”

Dylan isn’t the only one among our rock ‘n’ roll word-slingers to take at shot a Springsteen. Meltzer’s rules of “courtship” in The Night (Alone) specified Bruce was taboo:

If you want or need flowers, specify and you got ‘em. Earrings, crack, a back rub—anything within reason. Help you with the crossword puzzle, wash your dishes, cups, spoons (but not forks). No Sting or Springsteen…even passion has its limits.

Meltzer has hammered Springsteen over the years, offering musical and political rationales for his distaste. The Night (Alone)’s chapter on “Forgiving the Viet Nam Vet” threw shade at Springsteen. The Boss, of course, has famously identified with Viet Nam vets. He’s acted in solidarity with real vets and sung his blues for homeless bothers under the bridge (who once wore dress blues). His moves have been informed by his deep grasp of how class shapes life-chances in the USA. Not that Meltzer’s clueless on that score. He allowed there were folks who “accepted the draft to eat” but he worried about bowing to vets as a way to settle “CLASS MATTERS” (“lets redistribute wealth before the fact”):

[N]o encouragement should be given to young-hormone bozos, current and future, to think lifetime payback will come of serving their country—they sign up for a sick two year job, it doesn’t mean they’re entitled to a medal, a pension and a bungalow to take loans out on—it’s not like they’re coal miners or something.

Meltzer’s 20 year old argufying against retro jingoism has its hoary side since the military has come to look better than many other American institutions (and Viet Nam intervention seems more defensible too, btw), but his outcry against the “cattle car” has new resonance in the Age of Trump:

…there’s something every bit as cultural (for ex.: macho as surrender — tough guys don’t resist—obedience as dance step and rite of passage, the stigma of being branded a peacecreep or sissy, mindless discipline as badge of virility) and in the end run as crudely purposive about getting in (or not getting in) the cattle car. If anyone’s guilty, they’re guilty — those that went — of crimes against self and MEGAMULTIPLE OTHERS.

Fuckit the imperative was for everybody to get out of it, see a $10 shrink, fake deafness, cut off a finger, or just tell ‘em you’re a fag — whatever it takes — “community” scorn be damned. On a crass “survival level” you either went that extra yard to save your skin — pre having to napalm rice paddies to do it — or you didn’t. There’s culpability even in the docile accedence to pawn-hood, and if you’re already a pawn, the tropical death stink — and I ain’t talking yours — has still gotta make some bells go off…

Those bells went off for Springsteen in the late ’60s. He tells how he and his buds beat the Newark Draft Board in Born to Run, coming back to the great story (a staple of his raps in Darkness-era live shows) about how his father responded to the news Nam wasn’t in his son’s future. Doug Springsteen had often claimed to be looking forward to the day the army would get ahold of Bruce. But, once he knew his son would stay free, Dad mumbled it like it was: “That’s good.”

Yet Springsteen knows it wasn’t all good. Somebody did have to go in his place and he’s got friends on the Wall in D.C. My guess is Meltzer doesn’t and the idea of survivors’ guilt is more of an abstraction for him than it is for Springsteen.

Springsteen’s close-ups of working class facts of feeling prove he doesn’t need instruction on how ‘hood cultures may quash resistance to hard men:

I remember my mother in her pink curlers sitting on the steps, her ear pressed to the wall of the half house adjoining ours, listening to the couple next door scrap it out. He was a big burly guy. He beat his wife and you could hear it happening at night. The next day you’d see her bruises. Nobody called the cops, nobody said anything, nobody did anything. One day the husband came home and tied some small glass wind chimes…to the eaves of the porch. They came to disgust me. These peaceful-sounding wind chimes and the night hell of the house was a grotesque mixture. I can’t stomach the sound of wind chimes to this day. They sound like lies.

Springsteen once mocked himself (in song) as a “rich man living in a poor man’s shirt” but his class consciousness is more than wind.[5] Money doesn’t change everything. You don’t forget what it was like to be poor even if you consign the memory to a parens as Springsteen does here when he recalls breaking a tooth during his barbarian days as a surfer on Jersey beaches: “For the first time in my life I visited a dentist (previously it had been my old man with one end of a string tied to a doorknob and the other to my loosening tooth).”

I’m not out to diminish Meltzer’s protests against Springsteen, but there’s a line by a First writer David Golding that seems on point when it comes to Meltzer’s Great Refusal of Bruce:

The fundamental, perhaps even the essential class war in literature is twofold, having not only to do with the class war that takes place in reality but also the class war that takes place between failure and success, or between the writers whose words become surplus value and the writers who can’t even reproduce the conditions of their own revolting existence.

Meltzer has been exacting about the perdurable (note the absence of periods below) conditions of his own existence:

Famefortune has eluded me Fine Fine? Living in this shithole I’m invisible I’m amazed how I’ve still, that I’ve actually made a marginal living doing Never a middle class, or anywhere near it, but From not just what I write, that kind, for all these crummy little – but from writing at all Most writers, real writers, ‘re always chasing other work – they’re cab drivers or they’re mailmen or selling socks – that “enables ‘em to write,” it’s the normal While sapping them Or a teaching gig, if you can get, or keep – and writing can’t be “taught” – correcting papers of The drain on your juices – the daily/weekly time loss – it works both But when writing is your primary job – ‘s all I’ve basically done Hammer and anvil Fire The pitfalls of that Can it!

Meltzer would prefer not to poor-mouth his readers but he wouldn’t mind if they were alive to what he’s done that couldn’t be patented:

I’m the guy who introduced ‘ain’t,” “gonna,” “wanna,” deliberate misspellings, run-on, mixed metaphor, and most of that shit to rock crit, pop crit and beyond Plus regular use of all the cusswords That was my doing (true) (Give me a medal) Not to mention, dot dot dot

New Dylan/New Joyce

Meltzer’s most heroic stage may have come when he dived out of rockwrite into other outlaw streams of consciousness. Dylan’s apothegm about “listening to Billy Joe Shaver and reading James Joyce” provides counterpoint here. And there’s an anecdote of Springsteen’s that’s been echoing in my lit pitch-man’s brain. Capitol records once put out a promo 45 for DJs of Clive Davis reading aloud the word-drunk lyrics of Springsteen’s “Blinded by the Light.” How’s about a spoken word record of this passage from Meltzer’s “I Never Fucked My Sister”?

Our forebears gone out anneversing, we watched a Bing Crosby movie, then a Dan Duryea movie, than a Forest Tucker movie as I inched close, crept close with my brains bounding and my blood pounding, and I reached ‘round and found/felt her titnotyet, cupped a cloth over tintotthere, but I can’t lie, I won’t lie, I probed not between (nor beneath) (nor behind) for her fawn warm particular, and I ne’er got to sensate her eatmeaty mystery, to know, love and linger in eternalnot sweet daydamp multiradiant napkinwhtie monochrome savage dull vacant-throbbing allnight nonight drywild still rivulant irrigant arrogant aberrant errant napppy snappy toasty yeasty thirsty pasty smooth verticalnurturing sour calm sheethot gumthumbed thighhigh rumpplump footloose shoeleathersquidsatin storied moneyed squalid valid varicose bellicose viscous bisquous lifedangering strangering fullservice foolflattering clattering madgladding highwaywidedned dreamtime realtime wraparound flaparound socktight assbare whiskyswilling swineswollen graceboding ambushgoading asymptotic urneurotic peevented shescented mousenested quacktested sheepshorn seatorn thinsweaty readyteddy doorlocked lockbroke luckstruck indeliblestaining squeezeteasy allknown allknowing soleconceiving nevergreenpoainted undefileddefiled puddingbeyondknowing beyond imagining.

Master Class (or P.S. I Love You)

A first line should open up your rib cage. It should reach in and start your heart backward. It should suggest that your life will never be the same again.

The opening salvo should be active. It should be urgent, full of information. It should move your story, poem forward. It should open your reader to everything to come…

When I came on this passage in a newly published guide for young writers [6] by a distinguished novelist (and writing teacher), I flashed on one of Meltzer’s openers in The Night (Alone):

“I’d like to stroke your cock.” Well, okay, good. She’d rejected the offer of congress in a shaded patch of brush not fifty yards distant…

To find out what happens next, check the chapter, “Calling All Cubists.” But you’re on your own now! I gotta go back and fix the clunky opener of this here essay!

Notes

3 The only arena shows that worked for this author, FWIW, were Fania Latin music extravaganzas in MSG, thanks to mass claves which kept bands from sounding like one hand clapping.

4 Springsteen’s vocation still requires him to be an object of desire. He puts in work there. He keeps in shape and a New Yorker profile from a few years back alludes to plastic surgery. Richard Meltzer was once a good-looking semi-Romeo, but stopped worrying about his presentation of bod a while ago. In Autumn Rhythm (2003), he recalled how he looked like “Robert DeNiro (the young DeNiro). Now I look like Ulysses S. Grant.”

5 I once blamed Springsteen in my head for trying to escape from history he’d tracked in Darkness on the Edge of Town (1978). I remember zeroing in on his song, “Point Blank,” convinced that early versions, which I’d heard on bootlegs, beat the one that turned up on The River (1980) where Springsteen’s class-based rage seemed to get diffused/defused. “Point Blank’s” changes once seemed symptomatic of how Springsteen’s prior coming to class consciousness got trumped by hungry hearts and imperial middle “passages”—the way of all boomers. While class was once again a key to his map on Nebraska (1982) that record’s production seemed like a formal cop-out. I’ll allow my response to Nebraska was shaped by a simp’s faith in the, ah, only band that mattered. Back in that day, I bought into The Clash’s self-mythologizing as well as dim visions of rad pop progress. A year or two after The Clash’s Sandinista, Nebraska’s folkie Americana/protest sounded backward. (I don’t think I’ve ever given it a fair listen, though I dug the later, electric band versions of “Atlantic City.”) Ye olde politics of culture seem quaint now, yet Born to Run suggests I wasn’t way wrong to pick up on how British punks were (per the Boss) “frightening, inspirational, and challenging to American musicians.” In liner notes to The Promise (if memory serves)—the lovely CD Springsteen made out of music he’d left off Darkness to avoid sweetening that album—he gets deeper into his punk fandom, recalling how he’d take breaks from making Darkness for trips to the Village where he picked up imports of UK punk singles and EPs. Springsteen’s account of hearing these shots heard round the world brings home how stakes were higher for him than for amateurs (like me and my crew) who didn’t feel so compelled to comprehend what was comp for a pro (until the Clash blew our minds by opening their first New York show with a coruscating “I’m So Bored With the U.S.A.”). Springsteen’s clarity about what was alien in Brit punk is a reminder there’s something to be sung for the exceptional nature of Americans’ struggle for happiness. Born to Run hints Springsteen has always sussed that even in those aspirational moments when pop life has telos, no musician anywhere should try to ride a wave that’s entirely outside his or her own inwardness. Pop’s endgame isn’t to make the world choose between Combat Rock and silly love songs. (And of course there are better options on both ends of the political v. personal meter. Like, say, Sandinista and Tunnel of Love.)

6 Letters to a Young Writer by Colum McCann.