A conversation between Benj DeMott and Celeste Dupuy-Spencer about her painting of the Capitol riot, America’s politics of culture, Christianity and Country music…

BD: You have a rep now for “painting the news” from Hurricane Katrina to the downing of Confederate Monuments. When did you know you had to paint the insurrection? (I remember watching the first sequences at the Capitol with my kid and it seemed less than grave in the moment. I feel embarrassed now when I look back on it and think about how I was dumb about the danger…)

CDS: Well, I actually did not know that it was something that needed to be painted. I was watching it and taking it really seriously, but I’m always trying to stay aware of the heightened levels of anxiety that are built into the matrix of how this country is working right now. And so I was trying not to get swept away by, you know, the CNN of it. Still, I feel really concerned about the foot soldiers of the right wing. So when I saw people flooding the capital, there wasn’t a part of me that thought all of a sudden they’re going to succeed and there won’t be a transition of power. But I take extremely seriously the dissonance between the two actual realities that people in this country are living in. Partly because over the past couple of years, I’ve been experimenting with how the world looks when you shift your beliefs. I have somehow sort of figured out the algorithm that allows me to switch up my way of seeing the world, you know, while keeping a foothold in my actual belief system. I just think I understand from the inside that there’s something enormously dangerous about where we are right now…

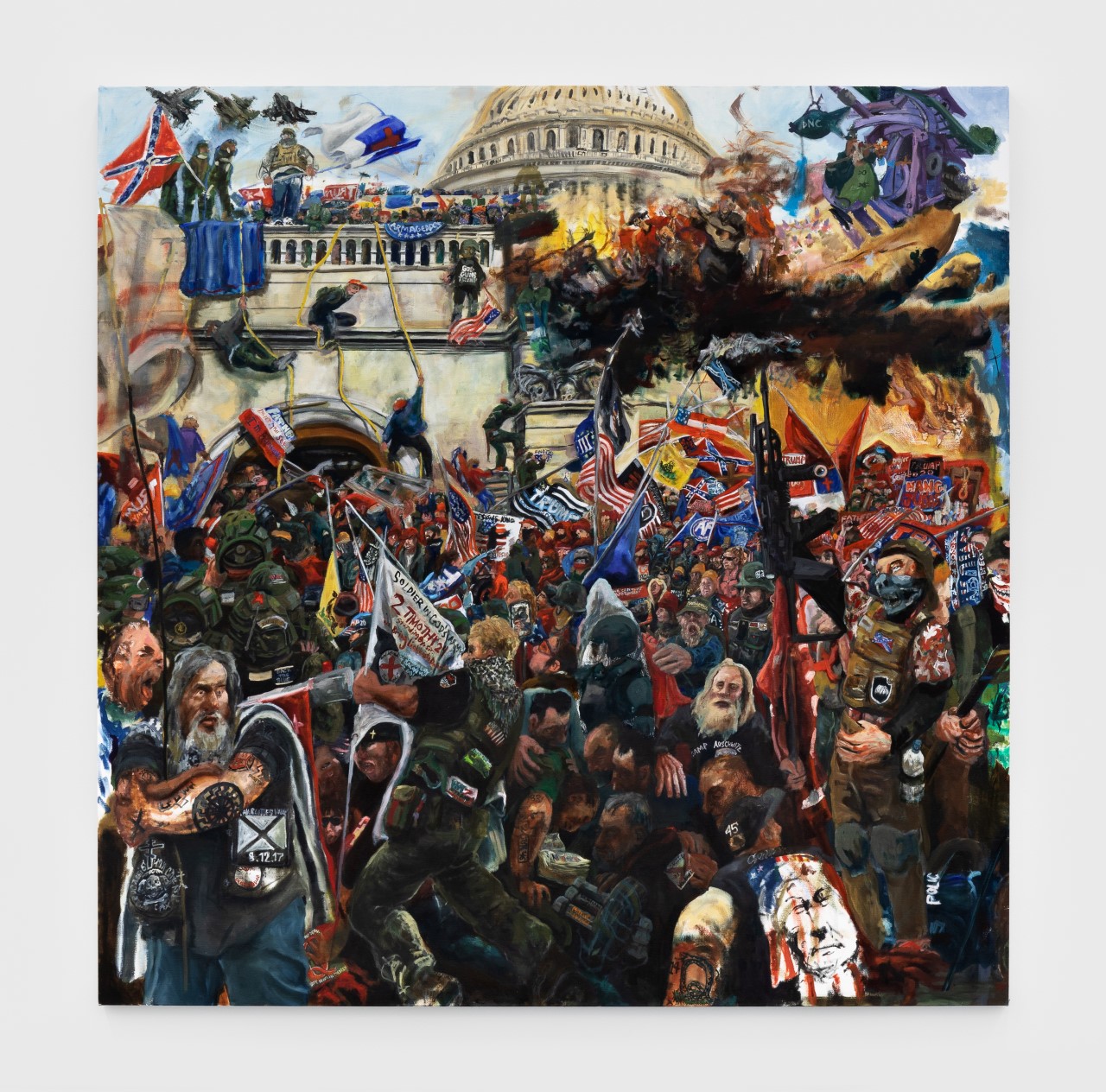

But in terms of painting it… I had a show that I had to prepare for and I hadn’t started it. My paintings usually take years and I only had this big canvas. And then I was like, all right, that’s fine, I’ll just…start painting. But I didn’t have any idea what I was going to do. When I’m about to jump into something, I look through books of paintings. So I was looking at one of my favorite Tintoretto paintings. It’s Moses getting water from the rock. This was just going to be how I get paint on the canvas. And all of a sudden…the riot kept on going. But I can’t paint it. I don’t have time. I’ve got to get ready for Brussels…Once something starts, though, there’s nothing I can do. And I was like, OK, well, I’m just going to paint this riot. Once I committed to it, it just sort took over. In terms of how fast it went? It was sort of automatic. And I realized that the sort of frantic nature of how it had to be painted was actually incorporated into the painting itself.

I sort of went with the crowd…I couldn’t do anything with space. So the short answer is, I never knew until I was about halfway done with the painting, at which point, my gallerist, Nino, called me and said: “This can’t go to Brussels—this has to be shown here.” And he rearranged his entire schedule at his L.A. gallery in order to show that painting in a single exhibit exhibition…This all came at a time where I’m worried about what I’m doing with my life. I’m making, you know, high end luxury items, basically. I’m cutting a wrist to do it and they’re just…It sort of brought it back to a place where painting and people actually mattered. Having a show with a single painting, in an Art Market-driven world where artists are expected to produce enough work to fill up the walls of galleries at least once a year, challenged the assumption that people really don’t have the attention span anymore to look at one painting long enough to make a gallery trip worth it. Which is all really different than the way it was when artists would spend years on a single painting sometimes, and then sort of unveil it, at which point people would come, more like going to the movies. This isn’t really an opine. But having that show, having people make their way there, during a pandemic, no less, reignited my excitement about painting and my sense of, ah, vocation.

BD: That’s beautiful. I’m reminded of a 60s moment when the poet Philip Levine wrote a great (but not too grand) one called “They Feed They Lion,” which he thought was his peak (“it’s better than I can write”). He wrote it after the Detroit riots. He had a clue about where he was going, but he didn’t rush it. He walked around for a few days letting it germinate. He’d learned by then to take his time – “If I’ve got something, it’ll come.” It was cool you had time, though I guess you were still dead-lining…

CDS: Yeah, and you know when you have a painting that’s urgently coming out, it’s not just the painting taking over. But also all of my preconceived notions…That’s why the actual painting didn’t really come until about twenty-four hours before the opening. Because my critical brain didn’t have a chance to resist my political reflexes. And in this situation, because it’s a right wing riot, all of my worst instincts were coming out. Up until the day before the opening, I was really, really close to just slicing the canvas. At that point it would’ve just been propaganda: “Here’s this bunch of right wing idiots attacking our holy houses of liberalism…”

BD: You were clear about not going there in that statement that accompanied the painting and it was cool that that First respondent, whose own parents weren’t too far gone from the Capitol rioters, didn’t imagine you were painting down…

CDS: That statement the gallery and I wrote was a last ditch protection against people who came thinking they were there to see a painting (by a good liberal just like them) about how upsetting it is that uneducated backwards monsters with ridiculous fashion—and mark my word, bad table manners—stormed OUR Capitol! Like it was painted out of a sense of love and anger in Defense of the Myth of America. I want class-bound viewers to sense there’s actually an indictment of them in the painting.

The guy whose comments you sent was right on, though. It’s a bummer people had to read the statement to see the riot as a tragedy. But we are humans and we always feel our best when we’re comparing ourselves to someone we’ve deemed deplorable. Up until two days before the opening I was completely lost about how to make this painting reflect the viewers’ gaze—to make their gaze a central theme in the painting like the Impressionists did, only without implying that they needed to be more empathetic towards anyone.

I decided to go lead-heavy handed: a cartoon walrus and carpenter and their house on which I wrote DNC, Joe Biden’s planes flying overhead to bomb Syria, and the press release. After all, why be subliminal and subtle when you can be heavy handed and didactic and subliminal?!

BD: You called your painting “Don’t You See I’m Burning” – (that hit hard because of my own cool response when things started to jump off). At the gallery website there’s another header: “The Dream of a ‘Burning Child’” that points directly to that amazing sequence from Interpretation of Dreams…

A father had been watching beside his child’s sick-bed for days and nights on end. After the child had died, he went into the next room to lie down, but left the door open so that he could see from his bedroom into the room in which his child’s body was laid out, with tall candles standing round it. An old man had been engaged to keep watch over it, and sat beside the body murmuring prayers. After a few hours’ sleep, the father had a dream that his child was standing beside his bed, caught him by the arm and whispered to him reproachfully: ‘Father, don’t you see I’m burning?’ He woke up, noticed a bright glare of light from the next room, hurried into it and found that the old watchman had dropped off to sleep and that the wrappings and one of the arms of his beloved child’s dead body had been burned by a lighted candle that had fallen on them…

I first took the Freud title/reference as a comment on the failure to take in the seriousness of what was likely to happen as Trump kept firing up his base even after it was clear the election was over and he was cooked. It’s clear to me your angle on this is wider and takes in the responsibility of all of us who’ve missed how and why what you call the foot soldiers on the American Right are burning. How did you came across such a perfect image for the state of our country?

CDS: I have politics but one of the most important things for me as I enter all my paintings—actually the thing—is psychoanalysis…the interior life of people. And, you know, despite Marxist scrutiny, it’s Jung who matters most to me. I have a Jungian analyst who I see two times a week…

Now because I also really care about things to be actually physically there, I don’t think Jung is the only way to think about the politics of the American dream. Jung is really good when it comes to how we take these things inside and allow them to change us and connect us. With Jung, things don’t have to be real to be true…

I got the “Burning” passage from this left-wing psycho-analyst [Steven Reisner] who has a really great podcast called “Madness.” While I was painting, he just sort of downloaded it on me. He took that Freud thing, which I’d been aware of, and he connected it to the American Dream, which I’m obsessed with.

I think a lot about the American Dream because I’ve seen my personal story being hammered into something that it wasn’t by the Art World. I’m supposedly some kind of primitive: “I don’t know why my art’s good. I go to the county fair.” They don’t understand that my father’s [novelist] Scott Spencer. I’m not like some hillbilly, right? But they’ve got this thing in their brain. So I’m thinking the American Dream is like an assault on our psyche. These Art World people are suffering from the Dream. I know I am. And so I analyze it…

BD: I hear you. They’ve turned you into the exemplar of the Dream when you’re saying NO! But I’m also wondering if the Dream is all mythos. Maybe one key is that America is so big. (Not that that’s not a problem.) Size makes for more ways up or around because the hegemaniacs can’t control every gate. I’m reminded of Ta-Nehisi Coates musing on the meaning of his American story. He was doing time in France and he came to doubt he’d’ve ever found a way to get himself heard in that country if he’d come up there. America may be more open to underdogs because there are more routes up and out over here?

CDS: I think that’s a myth. And Burning speaks to that. Freud give you a way to communicate the damage done by American Dream, though Jung gets at what I’m really interested in. That is: what we all believe in that we don’t know we believe in. I once sort of allowed Jung to carry me to the evangelical church. That’s where I realized that even in a household like the one I grew up in—a fundamentally atheist one—the American Dream gets inside individuals like an evangelical doctrine. One of my concerns in my work is to get people to understand their intellectual and emotional failings so they don’t just slam the door on things they disagree with. That kind of individualism you talked about before actually blinds us so we assume that’s just the way it is. And we don’t understand that these are actually notions that are given to us. We are sort of primed for obliviousness. We don’t even feel the water we swim in. I was misquoted recently in a magazine that had me saying “I don’t believe in a Sky-Daddy.” What I’d said was the moment atheists hear about evangelicalism, they think: “I don’t believe in this Sky-Daddy.” And so they can’t enter into this belief system. But I found I’ve been walking around with my own uncontested belief systems like a fucking evangelical. And so I’m able to kind of come at things differently and less dismissively…

As for Jung’s Collective Unconscious, I once thought that was some insane thing like thought patterns that conjoined in a cloud. But it actually comes by way of advertisements or school or…It’s not like a supernatural entity. It’s what’s in between the lines on the newspaper. As human beings we’re programmed to create and adjust our behavior and our perspective (which is a hallucination to begin with) based on the path of least resistance. And it’s so subtle that we don’t even know what’s happening. That doesn’t mean we’re all like automatons. But we’re all… influenced. And we think of those influences as our ideas.

BD: Let me come back to your attempt to make your audience more conscious of its own ways of seeing. In that art gallery statement accompanying Burning you pointed to the broader culpability of everyone who’s enabled Trump by failing to respond to the unraveling of America’s working class. I’m guessing you see the riotous crowd as representing not just the relatively well-off operators in Trump’s constituency, but also those who believed he was their Tribune. And in that case, the fever speaks to the condition of those white working class people who have been coming down again and again for decades. Since you’ve done time with Americans, white and black, country and city, people who live beneath the middle classes. Do you want to say a little about how that experience has shaped you and your paintings?

CDS: That is a really big question. I think that one of the ways it shaped me is what we were talking about before. My family of origin is actually kind of split down the middle. My father who grew up completely working class and is now not, and then my mother, who grew up kind of middle class. In terms of myself, I sort of struggled during the first 30 years of my life, waking up in cold sweats about whether I going to be thrown out of my house. I’m not saying that this is all about finances, because I know everybody can go through hard times. I understand this is actually a cultural question. What’s been important for me is my disillusionment with liberal identity. Basically, you know, growing up in a liberal household and thinking we were sort of righteous and, you know, superior. After all, we were all color-blind and I grew up gay. And so I must understand outsiders. Then having that all collapse. I’m embarrassed as I watch the way liberals look at the American working class—the right-wing American working class. It is with such disdain and contempt and inability to see them as they are. Liberals are, you know, people who are sure they know and so they end up not-knowing. And I feel like I know how they think. I have an insight into it though that doesn’t make it any less deplorable. (Just to use that word.) I don’t want my stuff to be a kind of easy apparatus for them—like a barge ferrying all the things they think they know, which, once it’s landed, in turn, sends a ferry back with the message “you were right!!” Or in this case, “you were right, these ARE the bad ones! You’re good, relax!” To be clear, I’m not trying to say the rioters aren’t seriously dangerous and scary. I’m just saying that that doesn’t make those of us on the other side inherently good. Anyway, my drive is to direct the gaze so that it bounces back at viewers. It’s like with the Impressionists. Manet’s…

BD: “The Bar at the Folies-Bergere”?

CDS: Yeah. And, you know, so all of a sudden the viewers are implicated. And so I’m trying to steal that hokey…

BD: Ah, but it’s not so hokey!

CDS: I always thought it was sort of a gotcha and maybe it is. But now that I’m using it, it’s actually a big deal. People are walking around not understanding how affected they are and how that refusal makes them impervious. So they’re not only affected, they’re completely impenetrable. And all of a sudden we’re living in two different realities.

There’s this idea that my paintings are about empathy. But I literally don’t care about feelings. I’m like autistic. I’m trying to do what? I don’t understand my own feelings! What I want is for people to understand their reflexive, nearly physiological responses.

BD: I noticed what might seem like the contradiction in this couplet in that Forbes piece on Burning: “‘I don’t think the insurrectionists need our empathy, or that we need to see their humanity,” Dupuy-Spencer says. ‘And at some point, we also need to forgive them, and accept them back into the fold.’” So on the one hand, don’t be too soft on the insurrectionists. And on the other, don’t make the bulk of them pariahs forever. You’re a double-truther…

CDS: Totally. They’re both true. I’m not out to humanize the right wing, or to ask people to concede to them. And I’m especially not asking that of those targeted by the right wing. “Yes, they’re racist, but they’re also individuals.” We are at this place, though, where even if we prevent a GOP nuclear winter, we will all still be here. This isn’t a video game. It seems like the left sort of imagines that in the end, if we’re right, the other side goes away. We have to find a way to be here together, whether we want to or not, while holding people accountable.

BD: But you avoided sticking it to most of them. That’s why you didn’t use actual faces. Though you did paint one. Camp Auschwitz! Fuuuck him!

CDS: Yeah, a big fuck you to him.

BD: Your decision not to spare him made me think of a story about “discernment” told by this priest in Haiti, Fr. Frechette, who’s sort of a saint. He went down to Haiti in the 80s as a priest and realized they needed a doctor. So he went to medical school. He’s been back in Port au Prince for decades. A priest who runs hospitals, an orphanage, social programs etc. Anyway, I wanted to pass on his story in part because his thoughts about moral judgment and forbearance reminded me of that quote you carry around with you that was written by the woman who died in the Holocaust. (I want you to read that into the record before we’re done!)

Fr. Frechette is always turning a hard gaze on himself—pointing out how he was oblivious here or self-enrapt there. He tries to act as if everyone is redeemable (including himself!), but he also teaches you there are dangerous mf-ers you need to be aware of. And that part of life is knowing they’re out there.

CDS: Yeah, but even with those who are irredeemable and who you need to steer clear of—know that it comes from suffering.

BD: I hear that…Here’s the swatch of Fr. Frechette’s story. To set it up, he’s taking care of a “bandit”—his all-purpose word for a bad guy—who came in to the hospital with burns covering 60 % of his body…

“Love your enemy.” Here it meant we must work to save his life, to relieve his pain. He is human. He has a soul.

We did work hard to save him. I tried to humble my feelings of disdain for him.

We accepted looking at him through the lens of God’s eye, and not just as a bandit. Jesus did the same, with his companions on Calvary, one on each side.

He is still alive, even though there is a maxim that his percentage of second and third degree burns (60%) plus his age (27) was his likelihood of dying (87%). His gunshot tipped this even higher.

It wasn’t long before we learned something of what happened to him. A warring gang had tied three women in a shack and set it on fire. He ran in bravely to rescue the women, and he succeeded in saving them.

As the saying goes, no good deed goes unpunished. Nor did his. The results were before us.

Back to Jesus and his astute God eye. This situation showed us Jesus’s vision that the weeds and wheat grow together. It must be this way, so nothing good is lost.

Every bandit may still have an instinct for goodness, a chance to be redeemed. This is the case for every sinner.

Of the two bandits crucified with Jesus, one still had a redemptive instinct for goodness.

The second bandit was not on Calvary as a decoration, or to center the cross of Jesus so there was symmetry.

He was there because some bandits have no such desire for redemption, right to the end. That’s how life is.

Just as our outer eyes squint, penetrate and scan rapidly over what we are trying to understand, our inner eye must be trained to do the same. It is called discernment.

Jesus’ eye chart is different from that of Snellen. From the example above, you can see that I still need glasses. I helped the man, but with disdain…

I saw through God’s eye a little bit. Enough to do the right thing. But…

Jesus is always trying to teach help us to see better, to cultivate careful and clear vision. After applying mud and saliva to the eyes of a blind man Jesus asked, “can you see?” He replied “I see people, but they look like trees.”

At least he, like us, was on the way to seeing. A little more mud and saliva from the Savior, and an extra strong prayer, bring us along further…

CDS: It’s really fucking beautiful, and this is the thing that I realized when I allowed myself to go there. The story of Jesus is fundamentally true. The teachings of Jesus are absolutely true. And I believe in and I love Jesus. I don’t believe that he existed.

BD: That all gets complicated. Right?

CDS: No, no, no. It doesn’t actually. I mean I don’t believe a word of this happened in history. But now I’m free to, like, love my fucking enemy. Look at those people that are invading the Capitol, look at the police that are pummeling protesters…Yes, they are probably irredeemable, most of them, but they’re also God in the nature of that person. I think there is something absolutely holy about all of them, because holy doesn’t mean divine. It’s part of reality. And that in itself is holy because that’s actually just the definition of holy, you know what I mean?

BD: For real, for real. You want to read me your passage from the death camps. That one gave me chills…-

CDS: I think they found this in a book in one of the women’s camps. Or they found it on a body…

Oh, Lord, remember not only the men and women of goodwill, but also those of ill will, but do not remember all of the suffering they inflicted on us. Remember the fruits we have brought things to this suffering, our comradeship, our loyalty, our humility, our courage, our generosity, the greatness of heart which has grown out of all of this. And when they come to judgment, let all of the fruits which we have borne be their forgiveness.

So things just are. And the violence is this flash and then…That sounds like I’m imposing. They don’t necessarily deserve forgiveness but things still unfold…

BD: That flash is my way into Caravaggio. So it’s the dark and light. I’m thinking of Mr. Chiaroscuro’s underworld where no-one is too safe and secure. Discernment is key. Nobody comes up casual or can risk obliviousness unless they’re actually asleep. Here’s John Berger on Caravaggio…

He was the first painter of life as experienced by the popolaccio, the people of the backstreets, les sans-culottes, the lumpen-proletariat, the lower orders, those of the lower depths, the underworld. There is no word in any traditional European language which does not either denigrate or patronise the urban poor it is naming. That is power.

Following Caravaggio up to the present day, other painters—Brower, Ostade, Hogarth, Goya, Géricault, Guttuso—have painted pictures of the same social milieu. But all of them—however great—were genre pictures, painted in order to show others how the less fortunate or the more dangerous lived. With Caravaggio, however, it was not a question of presenting scenes but of seeing itself. He does not depict the underworld for others: his vision is one that he shares with it.

I know you don’t want to talk yourself up – but do you see yourself in relation to the tradition Berger outlines and to Caravaggio in particular?

CDS: I really hope to be. I get worried about the genre painting and I love social realism as an influence too, but I don’t want to be a social realist. What Caravaggio was doing is just revolutionary. He’s anointing…He’s saying what’s holy is right here, right now. It’s so profound. The role of painting at that time was really set by the church. You know, they had strict boundaries so that viewers would meditate on what was depicted in a painting. The paintings were vehicles for religious experiences. What did the suffering of Christ feel like? And what Caravaggio was inviting people to do—and the church was mandating that the people do—was to look at the urban poor and meditate on how it would feel to be poor. It’s just revolutionary.

BD: He got accused of being a heretical painter, right? He got in trouble for transposing religious themes into popular tragedies. There are different ways of being a heretical painter now. You averred to not being able to paint Jesus. What did you mean…It’s un-p.c.? Un-woke?

CDS: I think it’s seen as anti-intellectual, as quaint. The assumption is our theory has gone so far beyond that. It’s not part of the conversation anymore, and I want to make it part of the conversation. You know often when Jesus is discussed, it’s either as a metaphor for social stuff. It’s all about church-induced suffering that the artist had to shake before they could come to New York or be gay or…It’s always as a sort of oppressive force. And what I want to do is use these stories at their fullest capacity.

What I’m doing in a way maybe does harken back to what Caravaggio was doing. I started inserting these stories from Jesus when I found myself addressing class today—painting people in the white working class like my first boyfriend, Ralph. He’s got nothing. You know, he was thrown out of society before he even made it to high school. He’s never been able to have a way in. And all of a sudden I’m going to paint him to bring up class to people that want to theorize about it in a liberal sort of rich person way. They’re going to buy his portrait and hang it on their foyer. I felt like this is a deep betrayal. I got sick when I started to hear people refer to the characters, the guys, in my paintings as “white trash.” “They’re so white trash.” “You’re white trash” as one said to her rich boyfriend who likes to drink Pabst Blue Ribbon. I found myself getting sucked into this position in the Art World where my paintings are selling and my name is…And I just thought if I tapped into these stories, which I was already getting pulled towards anyway, it would be a way to resist people’s preconceived notions about people who are alive today and maybe force them to respond to what they’ve already deemed ridiculous or beneath them. It’s actually really hard for me to put this into words I’ve tried a hundred times…

BD: I’m thinking of how Erich Auerbach did it in Mimesis. He invokes the Christian idea of figura, which is connected with soul and some essence that’s time-drenched but beyond time. Figura surely goes deeper than plain social realism. And it’s also connected with the idea of when you’re doing a Dante-esque character study, you’re also implicitly resisting the tendency to be disdainful of the unfledged, of women and so on…

CDS: Or to make money off them.

BD: They’re not to be fucking mocked.

CDS: And they’re not be emulated like they’re having a good old time. That white-trash-is-fun crap.

BD: You mentioned how your distance from Art Worldliness made you try out a kind of viewing party for your buddies. Tell me a little about what happened there and the logic behind your studio party.

CDS: Well when a painting is up on a wall in a gallery, it’s thought of as this final product. The idea is that everything I did was to get to the finished piece. But that’s not the case at all. Every move I made was because I was engaged in the act of painting. It was like a dance I was doing, which is also sort of a Jungian thing, but with parts of myself that I had no access to otherwise… I never look at a painting at the end and think: “I did that.” I’m never proud of the painting as though it came from me because my paintings are much better—not to brag. But, actually, I know I’m not smart enough to make them. They’re bigger than me. Right? So when they’re done and hanging on the wall, it just means that the deadline came down and these people came and ripped these paintings out of my fucking studio and stole them and sold them. And if that didn’t happen, they would still be there and I’d still be engaged with them.

I’m really happy with almost all of my paintings. And eventually I am able to think of them as a sort of complete. But I also know that when I see one again, I’m missing something since I don’t have access to it anymore. Like at the studio where I’d touch it up. It’s not looking back at me anymore. My paintings take a really long time. So there’s months where I walk into the studio and all the paintings turn to look at me. And they’re all sort of hurling ideas at me. And it’s really helpful to think of it as something like a hallucination. It’s not that exactly. It’s just this sense that I get that I can actually engage. The paintings open up their eyes and they’re looking back at me.

But something else happens when I invite people to my studio, and the paintings are sort of activated in that way. Usually people come into my studio and they look around and it’s sort of nice, but when they walk in during that chunk of time when I’m really engaged, they gasp at the energy in the place. And I’m thinking, first of all, what the fuck is that? As a person who believes the world is, actually, sort of material, what’s going on? But that’s when these paintings are most alive. So before the viewing party, I realized I was going to spend the next couple days awake and trying to get them to a place where they’d be shipped off to Germany. And I’m not going to be able to follow them because it’s the pandemic. But this is the time when I’m actively loving them…When they’re at their highest potential, you know. They’re somehow these living things.

Anyway I wanted to invite people in to see them then. And also there’s something about the way people look at paintings in a gallery when haven’t been sold so far. I’m thinking of those who say, you know, like the highest compliment, “I would love to buy that if I could afford it.” I wanted people to come into the space that’s covered in paint, you know, and see if I could somehow negate the desire aspect or that sort of grasping thing. It’s a problem with the system that loving something or connecting to something automatically turns into: “Do I want to have that?”

BD: I’ve lacked the acquisitive sense when it comes to thingy things and I’ll allow I’ve taken that as an indication not of moral height but as a sign my aesthetic impulses are kind of weak. In my experience the collector’s eye is often connected with a capacity to see what’s really distinctive about a work of art. My older sister used to collect folk art and she could really zero in on which one of, say, 30 versions of an image by a particular outsider artist is the One. Not that that’s the same as being someone like Bernard Berenson—a genuine aesthete who makes out like bandit by whispering in rich people’s ears which painting they should buy. Forgive the aside…

CDS: You know that aside is really essential to things I think about inside the studio. With my paintings, I specifically don’t want them to go to just anyone that can afford one, I want them to go to people who can afford many because at a certain point those buyers are also going to be the ones that save them. First-time, one-time buyers? That painting’s probably going to auction. Then who knows where it ends up. But there are those people who are actually able to make sure the paintings exist in the world. That sounds super-colonial but it’s super-complicated. I really try to make sure the paintings go to people who are not harmful or attached to institutions that are really harmful. Like the Exxon-Elephant Kill Museum of Contemporary Art. But you never know, money tends to come from things that are unethical. This is where I feel sort of nervous talking, because I don’t want people that have bought my paintings to think I have contempt for them. Some of them are people I really love and I hope I always have relationships with…

BD: Well I guess it’s just hard because a painting or a sculpture is a significant form of property in the way that a story or song or poem is not. They’re objects that are bound to be mixed up in the process of commodification…

CDS:…in the one unregulated market in the world. It all sort of prevents me from making relationships with certain galleries. These are things that are actually written into the content of a painting, including the price. Say I’m going to be making a painting about class or Christ climbing onto the cross. When people look at it, it’s impossible for them not to think also about the price of the painting. It’s part of the story. I haven’t found a way to take that into my art. My method is denial and that won’t do. But I don’t want to make paintings just about money. Still the prices are actually…unethical. Because of the figures and because everything is unregulated. Also I realize the reason why the prices of my paintings keep going up is because that’s necessary for those who’ve already bought them. It’s a way of catering to their need to increase the value of their investments. The paintings aren’t getting more expensive because of anything intrinsic to what I do as a painter.

So I come up against this problem, which is that I am a painter. I think I’ve been one since I was three years old. It’s how I see the world. It’s how I communicate. But I wish I had a different way. I realize someone might say, OK, well, don’t do it through the art world, right? But I have something to say. I want people to encounter the paintings. I need walls but they’re not going to hang them unless they can sell them and in order to sell, they have to connect with the money. So it’s very confusing. I just hope the paintings end up being useful when alien species come and that it helps them know who we were. I really do hope they have value beyond their price.

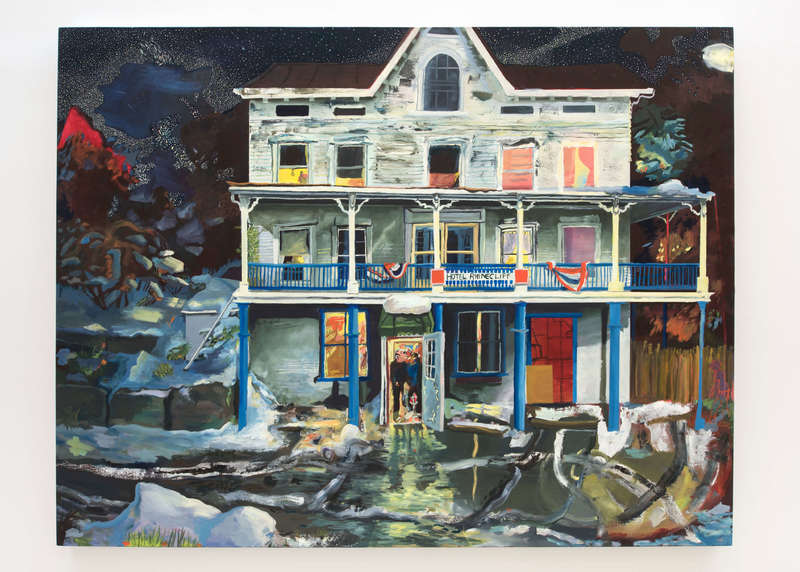

BD: On the value front. When it comes to alternatives to the given, I recently bumped into an article by a scholar (Gregory Sholette) who’s writing now (in the tradition of T.J. Clark) on artful representations of “the People.” And it reminded me you painted a lovely vision of, forgive the abstraction, solidarity at Rokeby. (See below.) I realize the smaller crowd partying in that painting wouldn’t be in tune with the rioters in Burning, but maybe they have something in common. They are livingly present as a group. And given the grid and atomization, it’s harder and harder to find that middle distance where you can hang together. You know the deal, sometimes it seems like Thatcher won and there really is no such thing as society. I was kind of wondering if you were having a little glow-y utopian moment envisioning that humane collective that’s easing into the sunset at Rokeby.

CDS: A little. Yeah. I know how toxic nostalgia can be but there was a nostalgia that went into that painting. I painted that before Trump was elected. Is that right?

BD: Yeah that’s a pre-Trumper.

CDS: God, my brain chemistry must have been totally different because I know that I wasn’t experiencing anything like the anxiety that came later. The approach…it’s just very strange to think that was only a little while ago. I was aware that class was my issue but what I was thinking about really intently at that point was race. With that painting, there was a nostalgia for a time and place in my history, but also I wanted to get at whiteness, which sort of meant that a lot of people were worried about whether they could touch me with a ten foot pole. I didn’t want to talk about whiteness as a culture necessarily, but I felt this need to push white liberals to understand ourselves. It’s about finding a way to actually see ourselves that’s removed from our desired position on race. It was a pre-Jungian thing but still trying to ask: what am I not aware of? Where am I coming from? What am I carrying into the world?

BD: There’s a brother in the painting.

CDS: Yeah. That guy exists. And that painting was one that gave me a sort of anchor. A way of hearkening back to a kind of sweet naivety. It was a way to attach to my history in order to be able to examine it from a friendly place.

BD: As an outsider, it did seem like an image of a true and only heaven. It’s such a gorgeous moment at the golden hour…

CDS: It was really amazing to grow up in upstate New York before it was the Upper East Side, before it was invaded by Chelsea Clinton. I mean it was 90 miles outside of New York City and redneck. And the woodworkers made fucking beautiful work. And the landscapers were chewing chaw, wearing cowboy hats and doing organic gardens. I had relationships with people that would be unheard of now. I was a teenager and I used to have the school bus drop me off at a bar. It wasn’t healthy. It was just my life. Drugs and alcohol and these people. And one of my closest friends was this guy named Scooter. He was homophobic. He was this redneck guy. We used to drink beer and shoot…He had this dart gun. So we’d throw the beers up…I was a teenager and he was in his thirties, but we loved each other and we would have these conversations that are off the table right now. You know he’d say, “No offense, but I really don’t like gay people.” To actually, like, engage with that in a place that was really loving and have it turn into, “I don’t like gay people, but you’re alright.” And then, all of a sudden, somebody called me like a homophobic slur, some blatant drunken bar night. And Scooter was up and at ‘em…

And so there was something about that place that was better then. I’m really glad it comes through somehow in that painting. I wish I had a way to articulate it a little bit better—a safer way. I don’t think my anecdote will go very far today. I don’t want to be put down as an apologist.

BD: Dicey times. I wanted to ask about your Red, White, and Blue hotel. I thought it was untitled, which gave me license to project, but it’s the one called “Early Snow: The Redcliffe Hotel.”

I jumped to Freud before I locked into the color scheme. I was thinking about the house as a metaphor for the self but then it seemed like nationtime: The House We Live In. Which wasn’t looking too stable in 2017 when you painted it. Not that it’s all good now. I wanted to read you a passage I came across in Isabel Wilkerson’s new book, Caste: The Origin of Our Discontent.

America is an old house…When you live in an old house you may not want to go into the basement after a storm to see what the rains have wrought. Choose not to look, however, at your own peril. The owner of an old house learns that whatever you are ignoring will never go away…Many people rightly say…I have nothing to do with the sins of the past. My ancestors never attacked indigenous people, never owned slaves. And, yes, not one of us was here when this was built…but here we are, the current occupants of a property with stress cracks and bowed walls and fissures built into the foundation. We are heirs to whatever is right and wrong with it. We did not erect the uneven pillars or joists, but they are ours to deal with now…When people live in an old house, they come to adjust to the idiosyncrasies and outright dangers skulking in an old structure. They put a bucket under a wet ceiling, prop up groaning floors, learn to step over that rotten wood tread on the staircase. The awkward becomes acceptable and the unacceptable becomes normal…

I thought I’d segue from Wilkerson to ask if you want to say something more about how you see yourself in relation to the nation. Maybe it comes down to your sense of place because you’re one of those people, not all that common anymore, who know from the south and the north. And you’re also at home in Cali…

CDS: That passage you read…Sometimes a metaphor is so right it’s like your toes are feeling around and then all of sudden your feet are on the ground.

BD: Well you should feel grounded. You painted that damn house.

CDS: But in painting it’s the ineffable. I often find myself using the tangible as a sort of Trojan Horse so that people are sort of distracted identifying what they see in the painting while what’s inside the horse is slipping out and into their heads…

The idea of nation is really important to me and it’s complicated, too, because at the core, I’m an anti-nationalist. Yet I realize that these ideals shape us. It isn’t that nationalist visions need to go unchallenged and only approached with love, but I think that basically the goal for me is to situate myself in the middle of the myths and crowds…

I mean, I was that person in high school. I was friends with the popular kids and I was friends with like the backpackers. And I try to take that sort of position even as I have my own set of ethics (and I don’t really stray). So I think the Nation is one of the mythologies that we live by. And even those of us who come at our myths politically tend to miss how it runs our own day to day lives. So basically, I never want to stand on the outside and point out what other people are doing wrong. I can’t punch down. I can’t pretend that I understand without going through the experience myself, you know? And so, from my perspective, what I see is the biggest sort of failure is this notion that if everyone had the right information, we could rise above all damage done by (and to) our country.

BD: Well I get the danger of imagining information is the way out, though I don’t want to give up on News (or fact-checkers). When it comes to nationalism, one thing I’m always alive to—maybe because I’m on the East Coast—is the dangers of received anti-Americanism. In this neck of the world so many people look to Europa for yada yada. So much so that they tend to be entirely oblivious to the riches of American culture. Actually that’s not the right phrase. It’s too close to popular fronting—that whole other nexus of leftist sentimentality about America. So not “riches” but just the interest of the goddam street where you live…

CDS: Yeah and not only is that foolish and counter-productive politically, it’s also people living in absolute self-denial. Its people imagining that we’re run by our best ideas and ninety-five percent of our day to day actions come from forces outside our own understanding. And my fear is that when people allow themselves to be removed—to have this sort of high sense of themselves, they start to believe that’s how they live their lives. That’s sort of what I was saying about whiteness. So I walk around and talk up anti-racism, when what I need to do is find out how this stuff is embedded in me.

BD: I think it’s time we went country. Lord knows, as you know, race is often an excuse for not going there so let’s do it now. I know you feel distant from elite Blue states of mind. Your painting has been more engaged with popular problems and facts of feeling. Country music is one key here…

CDS: People always ask me who I was looking at when I was making a certain painting, who my influences are, and there are for sure painters who I am deeply deeply influenced by, but the people who are just as influential to my work and how I see myself as an artist, how I’d like to become — it’s all country music. When I try to express that I realize people think I’m joking around or being flippant or I’m trying to act like I’m not as serious about painting as I am, but that’s not true. I’m dead serious about painting. I really do have Tintoretto on my right and George [Jones] on my left. David Allan Coe is there to remind me to dig deep and keep my heroes with me, and Randy Travis is there to remind me that even though I think painting is the only reason I deserve to exist, it’s not. It’s super cheesy…but I learned that from country too.

BD: Your faith in country reminded of a case statement by Peter Guralnick. It begins with a phrase I like which he applied to the original rock ‘n’ rollers. He speaks about “individualism in the extreme.” OK, so here’s his account of what got under his skin when he got into country in the 70s…

Individualism in the extreme, the embrace of life (the embrace of the future), the appreciation of eccentricity, the denial of category that has marked every great American artist from August Wilson to Merle Haggard, from Howlin’ Wolf to Mark Twain. It was the beginning of the so-called “Outlaw Movement” – but that wasn’t what drew me to Waylon or the music. It was, rather, his existential embrace of the moment so perfectly exemplified in his collection of Billy Joe Shaver songs, “Honky Tonk Heroes.” It was that same celebration of everyday reality, without any need for adornment or prettification, that I had first found in the blues.

I remember seeing Willie Nelson at Fan Fair around this same time, just after “Red Headed Stranger” came out (not long after his other great “concept album,” “Phases and Stages”) and being just as mesmerized. Neither Waylon nor Willie was selling anything but the truth. “Country music is just as serious as any other kind of music,” Waylon told me then, speaking of a proposed national television appearance. “They wanted me to do ‘We Had It All’ sitting on a horse. I couldn’t do that shit. I told them to fuck themselves. To them [country music] ain’t nothing but a goddamn joke.”

Guralnick goes on discuss a country music series from the late 70s where performers/performances “defy categorization or idealization. They are simply proudly, defiantly, and irremediably themselves. Just like they should be.”

How’s that come across to you?

CDS: It’s really good. But I would add another layer to it. Because they are very much themselves, yes, but in a way that makes it accessible. So that you realize that they’re singing about you too. Even when they’re telling their stories. That’s one of the reasons why country music saved my life.

I needed to be…parented. I didn’t know how to do things, like basic things, like be vulnerable or regulate my feelings. I’d never heard a person voice regrets without a sense of doom, and I certainly didn’t know how to say I’m sorry. It had always seemed a sorry was wrested out of you like a trophy of war. I really didn’t know how to handle what I saw as my failings. Had to hide mine—they were stacked against me, unchangeable, and ultimately unforgivable. I’d try to never look at them, let alone put them on blast to the world. I had no idea that so many of the most wonderful things humans have brought into the world came by way of failure. And probably most of our most horrible impulses come by way of shame at some failure. I had gathered early that failure was shameful. Not that I did anything but fail. But in order to look anyone in the eye I had to deny it or compensate for it, which meant I had to know more than whoever I was having a conversation with even if I didn’t, but sly-like, just so they’d think I’m totally following, not like some dude about to correct them. For years and years, I had to pretend I was something else, I was a thin veneer of cocky over a … person I assumed would be shocking to whoever I let see me accidentally. The bathroom kissing scene in The Shining comes to mind. This, of course, becomes a serpent eating its own tail because one of my earliest sins was difficulty learning, and my solution caused me to be further unable to learn anything, because to learn something, you have to admit that you don’t know it. In front of a person who does! Answer: pretend you don’t know simply because you don’t care, then bolt. And it took a lot of fucking work to crack all this stuff. It took therapy. But in the meantime, I could listen to music and let that come in. On top of never being able to fail, I also had no access to tears. I would never cry in front of anybody. And then…George Jones. The first time I really listened to him, I sat down at this table with a boom-box across from me and a thing of whiskey (it was before I had quit drinking). I just knew that something was about to happen, but I didn’t know what. I put the CD on. And he was singing about not just day-to-day failures, but his failure as a person and what it feels like. Now I know it’s not true. He’s George Jones and he’s beloved, but I know that he knows that it is true. (If he was singing about wishing he could stop drinking, he wasn’t 10 years sober singing about the horror from his Jacuzzi.) And he’s encountering this and he’s mourning and his voice—the song itself is a weeping. And I just started to cry for the first time, like active weeping. Every time I was going to cry before, I’d suppress it and just stuff it as far down as I could. But with George Jones, I was sitting alone at my house in Chicago and weeping for the first time in my entire life at 19 years old. Holy shit. And I was changed at that moment…

After that, I’m ready to listen to the radio. I’m expected to dislike country. I’m supposed to because I grew up in a house where, you know, those people are stupid. I mean, country music is rednecks. This sort of denial where Emmylou Harris is actually folk music. (I guess my father’s really into country now, but back in the day…) So I began listening to country and it was the 90s and I was really excited even if they were singing “Itty Bitty.” The truth wasn’t in the words necessarily. It was also in the sort of half-notes. That feeling of trying to find a place of pride where you aren’t disregarded and thought to be stupid. But not pride in your car or…Somehow the right to be taken seriously as a human being was in the nature of the fiddle. Over time, I started incorporating this. I didn’t have places to pull from in my day to day. I had no idea. You couldn’t say sorry, because if you’re sorry, then you were wrong and you’re just this jerk. But George Jones taught me. And Tim McGraw laid it the fuck out. And Kenny Chesney actually just said when she says, “I’m sorry,” say, “So am I.” Then I went, “Oh.” But not only “Oh.” It’s the way that you say it. If you want to be right, say you’re sorry…

BD: I’m thinking of the story about George. You probably know it. His daddy used to come home drunk, wake him up and say: “Sing George!”

CDS: And hit him if he didn’t.

BD: Jesus, I forgot that. I may have told you this George story before. But we were at this Upper West Side party around the time of the first Gulf War. The chatter got interrupted by a folk singer who insisted on turning the living room into a stage. He wasn’t coming through but he kept on playing one song after another. Nada protest songs and then one where he implored us to look into eyes. I’ve got this Irish buddy who turned on heel and headed for the liquor cabinet. We ended up in the kitchen that evening. And somebody had a boom box and we all started singing along with a tape of George. The host of the party was a black woman. She was from Mississippi. I remember she was standing in the doorway looking at our crew and listening. She may even have said something like “I came a long way to get away from that.” But she was fine with it that night. The folkie had prepped everyone for something real artful.

CDS: George’s politics are probably really bad, but he’s an artist. Like his brain is working for us. And this other stuff is just the failings of the world. But it’s funny, I had this assistant in my painting studio and he moved here from DC. He was like a nineteen year old black kid, just one of the greatest, sweetest people I’ve ever met—the little brother of one of my closest friends. And he didn’t really know about painting, which is actually why I hired him. He was a musician who worked with rappers and was into hip hop. One day I said: “I’m sorry it’s been too long, I’m putting on my music and it’s going to be country.” And he was like… “Oh fuck.” But I just had to connect with my paintings. And so I had it on and all of a sudden I hear this sobbing because some of the music I listen to is pretty heartbreaking stuff. And he’s saying I had no idea this is what country music is. People really don’t know. They just go, “I hate it.”

That’s what I used to think. And once I was able to sort of disassemble my ideas about country music over a period of time, I started to dismantle my need for…certainty. It’s this process that carried me into sort of experimenting with what belief is. I was able to shake the dogma—that requirement to be right or die. And country led me to my relationship with Christianity…

BD: Well that makes sense. I remember that moment when Vince Gill got his divorce in order to marry the Christian Contemporary singer…

CDS: Amy Grant.

BD: And he did that song that came right out of his heart where he asks his daughter to “Let Her In.”

CDS: Earnest, sincere. I love him so much. And that’s another thing that’s really amazing about country music. I am actually like a music evangelist. I’m now preaching to the choir, but here’s another thing. In a time when everything is so fucking cynical, you know, and irony is all, there’s Vince Gill. Or Tim McGraw cues up “Humble and Kind.” There’s not an ounce of irony. It’s only sincerity. And it allows people to connect to what experience actually is. Not some weird, superior interpretation.

BD: When we talked about doing a Q&A, I mentioned I felt bad because First had failed to take notice of Billy Joe Shaver’s death last October. You responded that Joe Diffie had just died of covid. (He went on March 29th, only a few days after he got the disease.) I didn’t know from Joe and you steered me to “Hollow Deep as Mine.” Your gloss on that was perfect: “I love the way country men tackle extreme feelings in a culture where men having big feelings is frowned upon. Their workarounds are poetry!” Can you give me a little more on Joe?

CDS: Joe Diffie was key the first time I turned on country radio. In my hometown I would jump over the country station. And one day I just went to 101.7. There were maybe eight songs that were on repeat at that time. Joe Diffie’s “John Deere Green” was one of them. It’s just a fun love song. But I realized after, like, four times listening to it, I knew all the words and could sing along. Then I bought the CD with that song and it was lovely. There’s this thing I like to do. I have a sort of lefty country playlist on Spotify and I have all these songs about class and money and struggles. And I’ve got a number of Joe Diffie songs on that. Like “Somewhere Under the Rainbow.” His stuff tends to be about finding joy on the margins but that’s important too. You know, not just bread, but roses too.

BD: You also steered me to Lee Ann Womack. Let me quote you on her:

Lee Ann Womack is, I think, the greatest thing coming out of country music. I’m sure you’ve heard the song “I Hope You Dance” — as much as I like pop country, it’s literally an abomination, like being tortured in hell to listen to it. And it shot her far beyond number one, like into outer space. It’s as though every song since “I Hope You Dance” has been her way of trying making amends to the soul of country. My favorite might be “Send it on Down.”

Listen to her trill when she’s finishing each sentence in the chorus of “Either Way.” Like a dove.

I feel like she is the Angel Cassiel of country music. “If These Walls Could Talk They’d Pray”? Genius. “Bottom of the Barrel” is the song I blast when I’m really close to walking away from the art world. IOW, I play it all the time!

I’ve been sending “Bottom of the Barrel” around to Country-positives. The Mekons’ man Jon Langford said he loved the song. Maybe the Mekons will cover it…

CDS: I like the idea of Lee Ann Womack of “I Hope You Dance” spreading like a slow fire from person to person as if she was a true underground insurgent country rebel star… Eat that country radio! I’ll send a couple more of my serious teachers. Late ones from George Jones and Charlie Pride who died of covid too. I wish that all of Charlie’s songs were as wonderful. You know, I guess he had to walk a very tight rope. He had to stay 100% vanilla. I’m sure he wasn’t ever able to really fly. This song is so perfect, but he’s older, things were different. I didn’t know he died of covid until months later. Every time I remember that it lands like devastating news…

BD: We could end with Pride but let’s try one more prompt. It goes to how artists get over-sold as solitary redeemers of the world, as figures who are removed from common life. I’m going to quote something by a writer named Charles O’Brien. I’m just recalling now he’s a stone country fan. I think his favorite music may have been house music, but he was a serious blues harmonica player when he was a kid and back in the nineties, when he was in his forties, he auditioned to be a singer in a band that was aiming for the Bakersfield sound. Anyway, in this passage, he came hard at a once eminent critic, George Steiner, who’d pumped up the otherworldliness of world historical geniuses like Shakespeare (as a way of burnishing his own cred as a “major” interpreter). So first the Steiner in itals and then the bolded skeptical voice of the country music lover:

Time and again I have sought to imagine, albeit indistinctly, Shakespeare remarking at home or to some intimate on whether or not work on “Hamlet” or “Othello” had gone well or poorly…I can picture him, just, expressing satisfaction over Feste in “Twelfth Night” or the compactions of syntax (still unique) in “Coriolanus.” And then inquiring as to the price of cabbage…What I am unable to do is to arrive at any thought-image, however naïve, at any impression of literary technique of rhetorical transport, however masterful, when confronting the author(s) of God’s speeches out of the whirlwind in Job, of much of the Qoheleth, of certain Psalms or considerable portions of “Second Isaiah.” The picture of some man or woman lunching, dining, after he or she had “invented” and set down these and certain biblical texts, leaves me as it were stunned and off balance.

What is not wrong with all this. Why just? It is hard to imagine Shakespeare – working actor-playwright, shareholder, impresario, and presumably as gregarious as today’s show-folk – not discussing the clown role with the company clown. Hamlet…and others would be similarly subject to discussion…Could someone write Ecclesiastes and then go lunch? It is precisely the book of someone who has never wanted for lunch!

Before I shut my pie-hole, one more country add-on. When I went back to O’Brien’s passage, I flashed on a bit in a Merle Haggard profile. Merle kept interrupting his interviewer to go to the kitchen where his wife was making potato soup. He had to make sure there was enough bacon in the pot…

CDS: That person who said that about Shakespeare fails to realize you can’t have Shakespeare without the humanity. And the nature of us is that we’re hungry and fallible. And some of the mistakes are so stupid and shameful and essential! How are you going to have Bottom in Midsummer Night’s Dream if you don’t know what it feels like to be a dummy? I mean that’s the reason why God came in the form of Jesus in our own mythology. So that he could be pushed out of a woman. It begins in pain and ignorance and dirt—among the animals.