Originally published (along with August Sander’s “Photography as a Universal Language”) in the Massachusetts Review in 1978. This re-print is tuned to the Pompidou Center’s current exhibit, Germany / 1920s / New Objectivity / August Sander.The lecture we translate in the pages following this introduction is one of a series August Sander gave on German radio in 1931. Under a main title, “The Nature and Growth of Photography,” Sander included such topics as “From the Alchemist’s Workshop to Exact Photography,” “From Experiment to Practical Use,” and “Scientific Photography.” Sander divided the history of photography into three periods. He named the first two periods of positive achievement after the daguerreotype and the collodion process. He defined a third period of decline, of Kitsch portraiture and confused aims, that had begun around the turn of the century. In his present he saw a possible fresh start with the “new objectivity” movement, which he thought might redirect photography to the true concerns that scientific and industrial uses of the medium had continued. Aware of techniques and interests very different from his own, like that in photogram and photo montage, Sander declared his allegiance to photography as a scientific and documentary, objective-reality-related, truth-telling language.[1]

In 1931 when Sander was fifty-five, he had exhibited and won prizes and medals and published his book Antlitz der Zeit (The Face of the Time) with an introduction by Alfred Doblin.[2] He was the proprietor of his own studio in Cologne. Yet he may have had mixed feelings about venturing into public speech and writing. The German educational system has encouraged such feelings in people who hold no degrees or titles, and Sander had none. He had learned photography by himself as a boy, and gone on to jobs in studios during apprentice and journeyman years.[3] Sander’s son tells an anecdote in the matter of the lectures which shows his father, nervously self reliant, self-willed, a little defensive, probably suffering microphone fright.

My father hesitated and was probably a little upset [at the invitation to lecture on photography]. He had never interested himself in writing. But the subject tempted him. After we had repeatedly promised to stand by him, he accepted . . . August Sander buried himself in his books and read. After a few days he began to dictate. My brother Erich, with the best intentions, smoothed over the somewhat awkward style. But my father’s vanity was wounded and he fired his instructor. Then my mother and I took over — at first full of confidence . . . When we read back his dictation — and we thought it needed correcting occasionally — my father would deny that he had ever said anything of the kind. He would already be thinking of something else . . . There were further difficulties during his speech-test . . . [but] he was unwilling to let an announcer read for him . . . my father gave his lecture himself. In spite of several sedative pills, he became nervous and confused the time, so that the supposed twenty-minute broadcast shrank to only thirteen. After a short pause we heard August Sander’s voice from the sky, “Well, what now?”… It was the first time that an important photographer had spoken about photography on the air, and he had done so absolutely in his own way.[4]

Beyond such human and humanizing comedy, Sander’s fifth lecture has seemed to us interesting in at least two ways. It includes a statement of Sander’s commitment to “straight” photography and to the photograph as document; it discusses what he saw as his discipline’s importance in the world; it tells us something of a belief that may be strange to us — that human physiognomy, the appearance of face and body, faithfully and thoughtfully recorded in a photograph, can speak truths about human character and experience.

First then, this statement, like others by pioneering craftsmen and artists, may add to our understanding of Sander’s work and of photography. Second, from the photographer who wrote “with photography we can fix the history of the world” in 1931 and in Germany, and who in 1927 had written in a “Credo to Photography” that he intended “to give an image of our time in absolute natural form” and “in all honesty [to] speak the truth about our epoch and its people,”[5] such a statement may have a special retrospective poignancy.

.

I want to address that special, second poignancy. The period of experimentalism, political and artistic ferment — of modernism — flowered vigorously but, we know, all too briefly in Germany. The political, economic, and social crises which fed experiment would ultimately smother it and the Weimar Republic.

Sander’s photographs, which show us some of the inhabitants, are an invaluable part of the epoch’s record and a product of its spirit as well. Sander had abandoned picturesque and painterly reproduction techniques in the twenties. He had begun to print on shiny, smooth, technical or scientific papers, without retouching, and gone back to purify older negatives. He had been making portrait studies outside the studio for many years: people in the open or where they lived and worked and could present the tools of their trade, on a country road or building site, in office or doorway or on the city street or in the farmyard. He seems to have been stimulated in his drive to produce an image of apparent total objectivity and clarity within a formally composed — or posed — sharply contrastful, black and white, monumental portrait conception, by a circle of friends, expressionist painters, with whom he was able to discuss the nature of painting, of photography, and their differing excellencies and limits.[6]

According to Willy Rotzler, the Swiss art historian and former editor of Du, “a peak in the employment of the different and sometimes contradictory uses of photography was reached around 1928.” We don’t know whether Sander would have traveled to Stuttgart to see the exhibition “Photo and Film” which Rotzler tells us “provided a magnificent panorama of all progressive achievements . . . from the then new ‘objective photography’ to the abstract experiments by the constructivists” nor whether the volume Foto-Auge (Photo-Eye) published in 1928 would have been one of the books in which Sander buried himself preparatory to his lecture. But the “tradition-shattering” impact and emphasis on “creative experiment” which Rotzler assigns to these two “important events in the history of photography” would have been felt in Cologne.[7] In the twenties and first in discussion with other artists, Sander seems to have clarified his plan for his major work: to record the German people of the twentieth century according to the estates, their classes or social groupings, and their work. With that record Sander intended to establish a typology which would show the expressive possibilities of human physiognomy within his society.

To this end Sander collected and ordered his work in his personal archives; a selection of sixty prints was shown in Cologne in 1927 and published in book form in 1929.[8] A contemporary statement, probably a publisher’s announcement, describes the work. “Sander begins with the peasant, the earth-bound man, and leads the observer through all the classes and callings, to the heights of the representatives of the most exalted civilization and down to the depths of the idiot.”[9] Sander portrayed peasants and urban workers, artisans and society ladies, bankers, priests, Jews and National-Socialists and revolutionaries of the left, artists, the lame, the halt and the blind, provincial business people and the unemployed, and derelicts and soldiers, students, political figures, mothers and their children, family groups and clubs. He was not interested in a subject’s name or individual accomplishment beyond a general category, although names have been added to identify a good many in postwar editions of his work. He seems to have wanted to test what human, specifically German, possibility their appearance could express when he placed them, nameless, inside his groupings, fixed as they had been by his organizing eye as representative types. Whether all observers will perceive the same “heights” and “depths” and whether these are to be judged in the tone of the blurb-writer quoted above, and whether these were indeed the same “heights” and “depths” that Sander intended, remains a central and teasing question. Can we consider the photographs not only as documents of a time and place and its sampled population, but as directly expressive, legible units? Sander, after all, wrote that “every person’s story is written plainly on his face.” He implies that we can read a person’s work and life, happiness or unhappiness, perhaps even good or evil, from a first visual impression, and that the conscientious photographer could tell us even more, even more plainly. But history continues to teach us the difficulties of establishing correspondences between human appearance and other realities: appearance shifts day by day and minute by minute, from observing eye to observing eye. Nazi Germany itself provides enough examples (we need only consider the people in Ophuls’ The Memory of Justice to be reminded) which make it difficult to retain faith in our final ability to learn to read accurately these — or any but the most banal or blatant — uncaptioned or unannotated photographs.

One needs to be deeply inside a culture to be able to read its nonverbal signs and gestures, postures and insignia, its — are they stern or stolid, fierce or earnest or only kindly — faces. Although vestiges remain, the Wilhelminian and Weimar culture in which Sander’s subjects lived their callings and physiognomies is gone. What the images represent — even as they present us with swastika or aviator’s helmet or mason’s trowel — may become as mysterious as the specifics represented in pictorial medieval typologies. We may need guide books to read Sander, as we need them to read the sculptured friezes and stained glass windows that represent the seasons and men’s work, vices and virtues, saints and sinners.

.

That Sander’s photographs survived in significant numbers was in part accident. The free creative, if confused and often contradictory, spirit that had made Weimar’s art part of international modernism, was quickly and efficiently expunged from the Germany of 1933. That year the art exhibits which pilloried and ridiculed modernism with brutal slogans and ugly display techniques, and which we end in the expulsion of works and of artists, began in various German cities. In 1934 what was left of the first edition of Sander’s book was seized by the Gestapo and the plates destroyed. The works of Alfred Doblin, who had written the preface, had been included in the infamous book-burnings that took place at major German universities in 1933. Sander’s oldest son was jailed for political anti-Nazi activity in 1934 and would die for lack of medical care — still in prison — in 1944. Sander himself seems to have been implicated and suffered at least one search-and-seizure. After 1934 Sander turned to botanical studies, to plant and landscape photography, which he was allowed to publish. His plan to record the German people in their unretouched functions and faces, honestly pursued, would by then have been dangerously subversive. During the war years, however, he was able to move a good part of his archives to the country. He added relatively few types to his collection in later years, but was honored with prizes and exhibitions after the war, and selections from his typology continue to be published and exhibited.[10]

It may be useful to recall names and fates of some others who had concerned themselves with photography in the twenties in Germany.

Erich Salomon, a very different kind of photographer and the first to whom the term “candid-camera” was applied, had also been recording unretouched physiognomies — often those of the powerful in moments of decision. His book, Berhmte Zeitgenossen in unbewachten Augenblicken (Famous Contemporaries in Unguarded Moments)[11] was published the year Sander gave his lectures. Salomon was to die in Auschwitz. Kurt Tucholsky and John Heartfield had published their picture book in 1929;12 they too had intended to arrive at an image, or cross-section, of Germany — again with intentions different from Sander’s. They combined wire-service photos with Heartfield’s photo montage and Tucholsky’s satirical essays and caused a scandal. Heartfield could flee Germany and continue his political work abroad, but Tucholsky killed himself in exile. Moholy-Nagy and Bayer, the Bauhaus theoreticians and practitioners of photography, were able to leave Germany and go on to American success, in 1935 and 1938 respectively. Walter Benjamin, critical theorist and man of letters, a Jew passionately interested in society and the arts, who had published his “Kleine Geschichte der Photographie” (A Brief History of Photography) in 1931, would die of Nazism.

Benjamin had singled out Sander’s portrait work for praise and sensitive comment. He compared Sander’s portraiture to the use Eisenstein and Pudovkin had made of nameless, class-determined human beings in film, and assigned to Sander’s work a similar “new and immense importance.” What Benjamin saw in Sander was what Doblin had seen: a “sociology without words” and a “comparative photography” through which students might arrive at the underlying type. Benjamin’s description of Sander’s sensibility — “unprejudiced, even daring, but tender at the same time” — is one that can stand. But Benjamin goes on to a passage which in our context is of even greater interest.

It would be a pity if economic considerations were to prevent the further publication of this extraordinary body of work. Besides that fundamental encouragement, we can offer the publisher another reason to go on with the project. Almost overnight, works like this one by Sander could gain unsuspected immediate relevance. The shifts in power that we can look forward to are of a kind to make a practiced and sharpened grasp of physiognomy vitally necessary. Rightists or leftists — we will have to get used to having our origins read in our faces. For our part, we will have to read their origins on the faces of others. Sander’s work is more than a picture book: a training-manual.[13]

There is heavy irony in this passage and it becomes bitterer if we know — as Benjamin could not have avoided knowing — the kind of picture book and training-manual that was actually a bestseller in Germany in the twenties and throughout the thirties. Not all racist theory was promulgated from the gutter by papers like Streicher’s Der Sturmer (The Storm-trooper). Hans F. K. Gunther’s Rassenkunde des deutschen Volks (Racial Elements of the German People)[14] first published in 1922, had gone through sixteen editions in 1933 and sold 420,000 copies by 1944 — figures which in the context of publishing at the time made it a sensational success. Gunther was appointed professor at the University of Jena in 1930, although he had none of the usually expected qualifications, and the book was favorably reviewed by professional anthropologists. We need not argue here whether Gunther was a “charlatan” as David Schoenbaum in The Brown Revolution maintains, or simply working at a level of investigation and induction now obsolete; the Rassenkunde must seem to us pseudo-science and repulsively tendentious. Written to a publisher’s order, the book was profusely illustrated with photo graphs, which gave it an air of providing empirical proof for its theories. It seems to have been the basic text to define Nordic racial characteristics and superiority, other European races’ concomitant inferiority, and what was then called the “Nordic Idea.”[15] It contained all the racial myths of blood and character and soul, of moral and intellectual qualities in inherited association with the shape of a head, hair and eye color, nose, forehead, and chin configurations.

.

The photographs, which may have accounted for some of the book’s popularity, are primarily heads in full-face and profile, six to a page; there are also some group photographs, often of people in regional costumes. The writer, in prefatory remarks, thanks friends and various professors and institutes for contributing photographs: the preface to the ninth edition specifically asks that pictures of people of “pure racial characteristics” be sent to the publisher, and enumerates the racial types especially needed. One might read all kinds of things in these faces; the captions, however, tell us what to see: for instance, “From the Silesian nobility. Dominantly Nordic.” or “Berlin. Mostly Nordic (with slight East-Baltic influence? Breadth of lower jaw?)” or “Freudenstadt . . . Dinaric. Forehead bulge plainly visible.” Or a clean, pleasant family group not unlike some of those taken by Sander: “Saxony. Grandfather (father of wife) and grandchildren apparently more Nordic than the parents.” There are more representatives of noble families and more military officers and obviously upper-class shirtfronts among the Nordics than the others; more wrinkled peasant countenances and folk-headdresses among the less desirable races. Physiognomy was — and would continue to be — a question of vital interest in the Germany that could not tolerate Sander’s photographic Face of the Time, or a Benjamin or Salomon or Tucholsky in the flesh. An appendix contains Gunther’s anti-Semitic treatise, Rassenkunde des judischen Volks (Racial Elements of the Jewish People) which was also illustrated with photographs.[16]

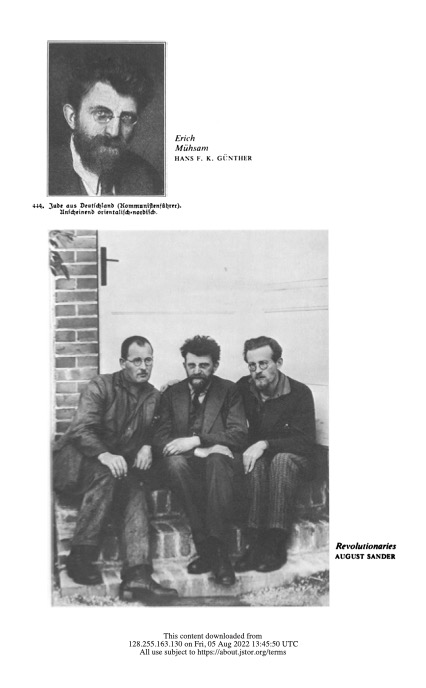

It is mere chance, of course, that at least once the same face appears in both Sander’s and Gunther’s collections of physiognomies. Still, such a chance occurrence might — like the belief in a speaking or telling physiognomy itself — point to unities within a society even as that society is in process of tearing itself apart. The face is Erich Muhsam’s, poet and anarchist.[17] Muhsam was well-known. He had been a member of the short-lived Workers’ Council government in Munich in 1919; he and Ernst Toller had called for the transformation of the world into a flowering meadow. Muhsam and Toller served prison terms together and Muhsam, who was arbitrarily arrested after the Reichstag fire, was finally murdered by concentration camp guards. In Gunther, Muhsam’s photograph — probably a publishing-house or book-jacket picture — appears in the Jewish appendix. Below the bearded, dark- and long-haired head — eyes, behind thin glasses, looking into the camera — is the legend “German Jew (Communist leader). Apparently Oriental-Nordic.” Karl Marx and Bertold Auerbach, the popular nineteenth-century novelist, appear named on the same page.

Gunther told his readers that physiognomies like those of Marx and Auerbach and Muhsam would communicate the message “alien being . . . incomprehensible . . . hateful” to the Nordic soul and that the Jewish soul could best be characterized as “rigid” and “changeable.”[18] And of course a good deal more we need not repeat. Gunther provided photographs, readings, and physiognomic theory for truly sinister parlor-games.

In Sander, Muhsam’s head is shot from a slightly different angle, and Sander’s portrait shows Muhsam between two comrades.[19] The three men are pushed rather closely together to sit on some neat brick steps. Their heads are backed by an expanse of pure white painted door with a sharply contrasting thin black latch. A bit of brick wall shows on one side. They sit with their knees awkwardly pushed up in front of them. Their trousers are rumpled and worn.

One foot extends down in a clumsy shoe, breaking the dominant horizontal organization. Their hands have the startling graceless prominence that seems to me typical of Sander. The two other men lean towards Muhsam in the middle and one has an arm around Muhsam’s back. The two others wear black-rimmed small round spectacles and one looks cross-eyed in spite of that correction. I am still close enough to Weimar culture to read in their wrinkled shirt collars and carelessly cropped or longish hair, that they cannot have been conventional professors or upper-class gentlemen. What else can I read on their unsmiling faces (only female actresses would have smiled for the photographer in Weimar) and their uncomfortably informal bodies? What did Sander, who classified them simply “revolutionaries,” expect us to read? Certainly none of the information and ugly speculation that Rassen-Gunther would have taught his readers to associate with Muhsam’s face and other wholly unlike faces.

.

We have an alternate reading of Muhsam from an authoritative source in the preface to Menschenohne Maske (People Unmasked), a compilation of Sander’s photographs published in 1971. Professor Golo Mann’s essay, written in 1959, tells us in no uncertain terms what we are to see in Sander’s photograph.

The way a person imagined the future and the ideal, so he presented himself. The three revolutionaries, who have here met conspiratorially on a stair-step, could not represent what they were more fully if a theater director of genius had thus posed them. Not nineteenth century revolutionaries — those had stronger faces. Not from 1959: there are no more revolutions, only power seizures. No, these are carriers of the dream-revolution, the European revolution of 1919, which basically no one won, except in Russia, where it was entirely different. And when we contemplate these bearers of the revolution, we understand why it won nowhere. They could have played “Soviet Republic” in Munich in 1919 and they might haven perished then; their fate might have caught up with them fourteen years later in Germany or a little later still in Russia. That their lives will be disastrous is written on their foreheads. Hands off, one would like to say. How can you hope to tear the tightly woven web of a modern society, make a revolution, exercise power? — Useless advice. They know better . . .[20]

It is really Professor Mann, thirty-two years after Sander’s photo was taken, who knows. Nothing of the sort is written, as the German phrase has it, on these men’s foreheads. Professor Mann brought his own knowledge of German history and his own theory of that history — perhaps also a theory of physiognomy — to his somewhat disingenuous reading. Heinrich Mann and Muhsam had been acquainted in Munich.

A German historian does not need to suppose or speculate about Muhsam’s life and political unsuccess, as it might be read from a photograph. He knows it, as he knows the face. This reading has all the spurious authority of informed hindsight. Once we know that Muhsam was hanged in a latrine in Oranienburg, we may judge that Professor Mann displays an excessively-distanced, elegant lack of charity towards nonsurvivors. When he reads Muhsam’s fate on his face, he suggests that we? — who survive? who know better than to revolutionize? who have stronger faces? — can resign ourselves easily to his fate. Or, in inelegant American: Just a born loser!

Even photographs as honest and straightforward as Sander’s, can be used to document every kind of opinion, judgment, or fashion in belief. In good faith or bad. The twenties’ racist and the con temporary German historian seem to share an implied faith in physiognomy as destiny, revealed through photographs. I do not know whether Sander’s brilliantly composed, intensely seen and rendered, portraits ask us to share that idea, or its opposite — that class and work determine appearance and character. I know they can startle us by the immediacy with which the subjects look out from their culture that already works to estrange them from us. They await, demand, a reading that will be “unprejudiced, even daring, tender at the same time.” From inside a different, visually careless culture in which venal human images multiply as products on the market, we can try to let our eyes — helped by a truth-seeking photographer — expand to take in ordinary mortality again made rich and strange. We can ask our minds and our emotions to undergo like purification.

NOTES

1 The German text, a typescript of the original lectures, courtesy and permission of Christine Sander, Washington, D.C, Sander Gallery.

2 Munchen, Transmare Verlag, 1929. (Unless otherwise noted, translations of titles and of quotations from the German are my own.)

3 Gunther Sander, “Aus dem Leben eines Photographen” (From a Photographer’s Life) in August Sander, Menschen ohne Maske (People Unmasked), Luzern and Frankfurt/M, Verlag C. J. Bucher, 1971, pp. 286-288.

4 “Aus dem Leben,” pp. 307-308.

5 August Sander 1876-1976: A retrospective in honor of the artist’s 100th birthday, 2d. Christine Sander, Washington, D.C, Sander Gallery, Inc. No pagination.

6 “Aus dem Leben,” pp. 307-308.

7 Photography as Artistic Experiment, Garden City, American Photographic Book Publishing Co., Inc., 1976, p. 86.

8 August Sander 1876-1976.

9 Quoted by Walter Benjamin, “Kleine Geschichte der Photographie,” Gesammelte Schriften, VII, 1, ed. Adorno, Sholem, Tiedemann, Schweppenhuser, Frankfurt, M, Suhrkamp Verlag, 1977, p. 380.

10 “Aus dem Leben,” passim.

11 J. Engelshorn Nachf., Stuttgart, Gathorne-Hardy, G. M. (Information in Erich Salomon, Portrait einer Epoche, ed. Hans DeVries, intr. Peter Hunter-Salomon, Berlin, Frankfurt/M, Verlag Ullstein Gmbh., 1963.)

12 Berlin W8, Neuer Deutscher Verlag, 1929.’3 “Kleine Geschichte,” pp. 380-381.

14 Munchen, J. F. Lehmanns Verlag, 1926.

15 All biographical and publishing information about Gunther and the Rassenkunde, except as noted, in Hans-Jurgen Lutzhoft, Der Nordische Gedanke in Deutschland, 1920-1940 (The Nordic Idea in Germany), Stuttgart, Kiel Historische Studien, Ernst Klett Verlag, 1971; in particular, pp. 28-45.

16 Rassenkunde, passim.

17 Rassenkunde, p. 460.

18 Rassenkunde, p. 476.

19 Menschen ohne Maske, photograph number 117.

20 Menschen ohne Ma