Putin has justified his invasion of Ukraine and efforts at regime change by publicly claiming his mission is to “de-nazify” the country. An argument that rings especially hollow given that President Zelensky is Jewish and his grandfather fought the Nazis along with three great uncles who died in World War II. The President has publicly remembered the Day of Victory over Nazism (in a 2019 Facebook post) as “our Thanksgiving Day”: “Thanksgiving for the fact that the inhumane Nazi ideology is in the past. Thanksgiving to those who fought and defeated Nazis.”

Putin, though, has some useful idiots, to borrow the eerily applicable Soviet era phrase, backing him up. Too many commentators on the left and right traduce post-Millennial Ukraine’s trajectory toward pluralism and democracy. They trash the Maidan revolution of 2013-14, though Ukrainian protestors then were on the hinge of history. It was a time when harder-than-the-rest winter patriots risked their lives to establish their country’s right to self-determination. According to a journalist like Jacobin’s Branko Marcetic, though, there was nothing heroic about that nation-time. Per Marcetic, Maidan is best grasped as “A US-Backed, Far Right–Led Revolution…”.[1]

So what really happened? Let’s begin with a basic outline of events. In November 2013, a wave of large-scale protests (known as Euromaidan) erupted in response to the shocking decision by President Yanukovych not to sign a political association and free trade agreement with the European Union. Yanukovych instead chose closer ties with his patron Putin’s Eurasian Economic Union, though the Ukrainian parliament had overwhelmingly approved of finalizing the agreement with the EU. Yanukovych’s betrayal made people search for democracy in the streets. Protests continued for months and their scope broadened, taking in the full range of issues festering in what amounted to a broken polity. A large, barricaded protest camp occupied Independence Square in central Kyiv throughout the “Maidan Uprising.”

In January and February 2014, clashes in Kyiv between protesters and special riot police resulted in the deaths of 108 protestors and 13 police. Per the report of the U.N.’s Commissioner of Human Rights’ “[w]hile some of the acts of violence appear to have been extemporaneous and incidental to the situation of unrest, the information available tends to indicate that the commission of violence against protesters, including the excessive use of force causing death and serious injury as well as other forms of ill treatment, was actively promoted or encouraged by the Ukrainian authorities.”[2] The first protesters were killed on 19–22 January and there were even more deadly clashes on 18–20 February. Thousands of protesters then advanced towards parliament, led by activists with shields and helmets, who were fired on by police snipers. On 21 February, Yanukovych came to agreement with the leaders of the parliamentary opposition that called for the formation of an interim unity government, constitutional reforms and early elections. The following day, police withdrew from central Kyiv, Yanukovych fled the city (he’d end up in Russia of course) as the Ukrainian parliament voted unanimously to remove him from office.

In the wake of the Charlottesville rally, the Charleston church and El Paso shootings, and January 6th, Americans have plenty of reasons to be wary of white supremacists on the loose. No doubt there were right-wing extremists in the crowds who lived and died during the struggle to make Ukraine a truly sovereign nation. Their presence will never not be dicey for small d democrats. What follows, though, are primary source documents that show why it’s wrong—morally and factually—to diminish the “Revolution of Dignity.” Euromaidan and the terrible yet awesome process of self-organization that started then must not go down in history as a neo-Nazi thing.

Before turning to those documents there are important ground truths to underscore. Euromaidan was a diverse insurgency from the jump. Back in cold and rainy November 2013, it was Mustafa Nayyem—a Ukrainian of Afghan origin—who called for the first rally after Yunakovych reneged on the Association Agreement with the EU. The first two victims in the struggle were an ethnic Armenian, Serhiy Nihoyan, and a Belarusian, Mikhail Zhyzneuski. The case for the Maidan’s democratic pluralism rests solidly on the results of the 2014 election where Far Right parties—Right Sector and Svoboda—received less than 5% of the vote. (That’s a percentage much smaller than those amassed by their Western European counterparts!)

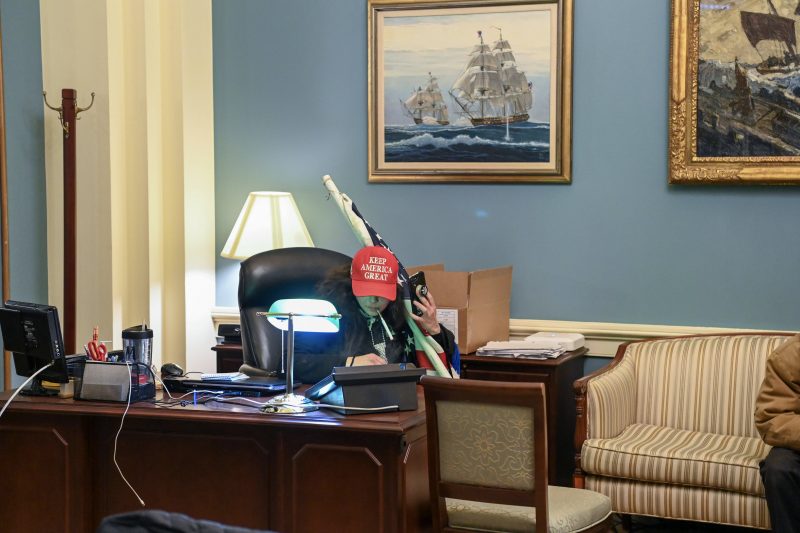

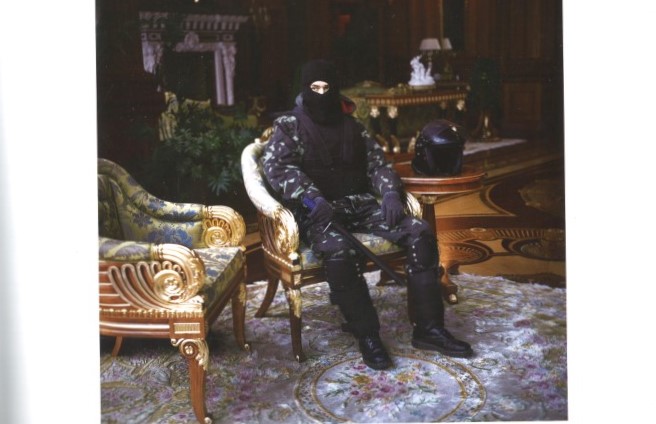

The first set of primary documents are two photos that implicitly compare the January 6th Capitol riot with the siege of government buildings during the Maidan (from the photobook #Maidan). Visually the two events are strikingly similar. (The Revolution of Dignity, though, climaxed with mass victimhood and victory.) It’s easy to conflate MAGA rioters with armed and balaclava-masked white men in Ukraine fighting the Power…

When you look at these pictures, though, don’t forget that January 6th is widely understood as a national disgrace, whereas Maidaners are remembered almost universally in-country as heroes. (Pace Mr. Marcetic.)

One of those who may “remember with advantages” is Volodymyr Parasyuk. What follows is his speech on Feb. 21st, 2014—the night before Yunakovych fled the country. Parasyuk spoke as a member of his particular sotnia (self-defense group) and as a (government of the people, by the people, for the people) person outside the political class. Parasyuk didn’t lean left or right. He was beyond faction, beneath and above pols dickering with Putin’s (and Paul Manafort’s) client Yunakovych.

A video of a performance by Okean Elzy—Ukraine’s most famous rock band (for good reason, their music is great!)—during the Maidan comes next. Music was important in the movement culture, and Okean Elzy were exemplary on this score. Their set and sensibility were tuned to Maidan’s cause.

This concert actually only happened because of Maidan’s unifying spirit:

There [on the Maidan] he [band leader Slava Vakarchuk] saw his band’s former guitarist; the breakup had not been very amicable, Slava and the guitarist had not remained friends. Yet finding each other that night, they embraced and decided to play a concert there a few days later with Okean Elzy’s old lineup.

Their performance would be the soundtrack to revolution:

Okean Elzy’s 2005 song ‘Ia ne zdamsia bez boiu’—‘I won’t give up without a fight’—recounted scenes of pouring glasses of wine with honey; the lyrics suggested a man struggling with a destructive love affair. On the Maidan the meaning changed: ‘Without a Fight’ became a theme song of the revolution. It was not the only one. Okean Elzy’s 2001 wake-up song, ‘Vstavai!’—‘Get up!’—now sounded prophetic:

Vstavai! Myla moia, vstavai!

Myla moia, vstavai! Myla moia, vstavai!

Davai! Myla moia, davai! Myla moia, davai!

Bil’shoho vymahai!

Get up! My darling, get up!

Get up, my darling! My darling, get up!

Let’s go! Let’s go, my darling! My darling, let’s go!

Demand more!…Slava’s voice was gravelly and intense. In that earnest voice there was something buoyant and mobilizing, but also steadying and euphonic… By the concert’s end it was nineteen degrees Fahrenheit, and Slava was wearing a t-shirt. ‘It was great,’ Slava told me later, ‘it was cold, but I didn’t feel cold.’

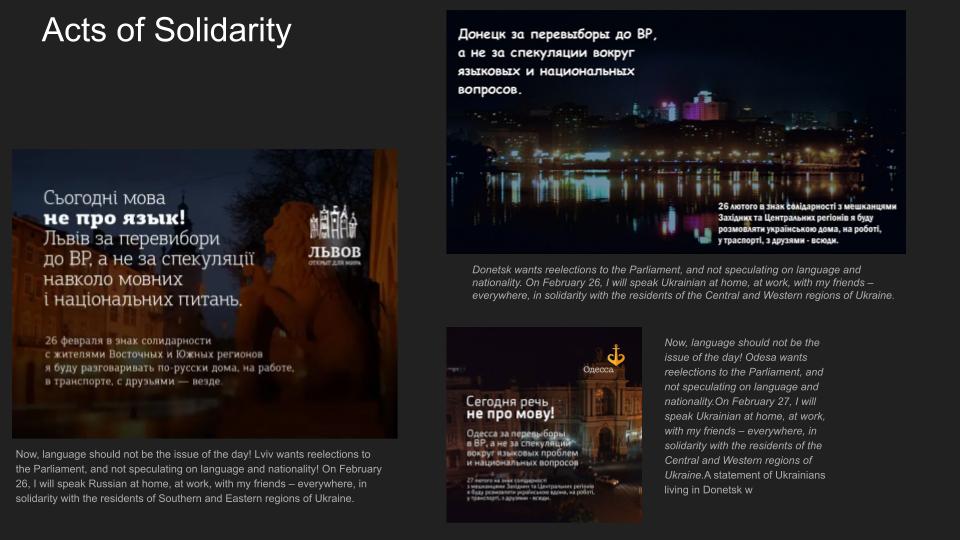

The next primary source document is a collection of social media posts from Lviv, Odessa, and Donetsk, in which the cities pledged to speak the language of their minority populations. These posts not only underscore the Euromaidan movement’s affirmations of pluralism, but point toward its manifestations outside of Kyiv. The posts amounted to a spontaneous, in-the-moment, but still potent critique of ultra nationalist Ukrainians out to quash the Russian language.

What’s next is a letter from Euromaidan allies distancing themselves from the Far Right. (Scroll down for the translation.) It indicates that many protesters were worldly types who would normally be repelled by intolerant extremists. (“It was the government of Ukraine, which was quickly losing any remaining semblance of legitimacy, that radicalized people that never belonged to any extremist groups. The government left the protesters no other choice. That is why the attempts to portray the protesters as fascist-like extremists is nothing but a ruse, a manipulation and a falsification on the part of the government, designed to absolve itself of responsibility for the clashes in center city Kyiv.”) This intervention is a reminder the movement blossomed from a student protest. It grew to be inclusive of city and country people, different generations, and various ethnicities.

Sticking with that theme, here is an interview with a representative of a minority on the Maidan—an anonymous Jewish leader. Such first person testimony is key for getting a granular sense of who really made the movement and how it worked. (FWIW, statistics on protestors’ backgrounds are pretty murky because people flowed in and out of the occupied square in Kyiv.) This Q&A goes deep into the dailiness of the struggle. The anonymous source is at once self-effacing and a natural-born fire-fighter. (To borrow a term from Lawrence Goodwyn, the great historian of social movements.) He understands instinctively that a party of hope must always worry about hotheads on its own side even as it refuses “moderation” that excuses apathy or quietism.

The situation on the Maidan is quite edgy, many people want to avenge the blood of the victims, who are even more tired of the inaction of the opposition—all these hotheads are full of illusions about real battles and, accordingly, do not imagine the possible consequences. They also do not think about the fact that there are also people on the other side of the barricades, so our actions should not discredit Maidan “with a human face.”

The anonymous Jewish Maidaner dismissed the notion that anti-Semitism was an issue at the protests:

There was not a shadow of such sentiments. From the first days I have been talking with activists of the Right Sector, UNA-UNSO—with all those people with whom in peacetime I would hardly have found common ground. At the same time, I position myself exclusively as a Jew, and a religious one at that. There are already dozens of resistance fighters under my command—Georgians, Azerbaijanis, Armenians, Russians–who do not even try to speak Ukrainian—and not once have we encountered a manifestation of intolerance towards each other. All of them treat my religion with emphatic respect.

This interviewee’s angle on Maidan is anything but beamish. That’s one reason why his real talk must’ve been bracing back in the day. Now it gives you another kind of lift—a prophetic one…

I don’t idealize the protest movement at all and I don’t know if a new civil nation is really being born on the Maidan, but some processes impress me very much. For more than 20 years, with all the external attributes of statehood, Ukraine was a very artificial entity—people did not feel pride in their country. The old stereotype “my hut is on the edge” was cultivated, Ukrainians were presented as a people who don’t give a damn about anything. No one expected that 9 years after the Orange Revolution, after a complete disappointment, people would find the strength to rise again. On the march of millions—and I participated in it—dozens of Jews walked alongside Svoboda, who shouted slogans that were unpleasant for me … There is little doubt that the spirit of freedom and unity is present on the Maidan in increased concentration. It is enough to walk along the barricades—we have not seen such responsibility for a long time, I myself in the past witnessed how people simply passed by a fallen person in the street. And suddenly a civic consciousness appears—people who work all day long stand on the Maidan at night, carving out a few hours for sleep.

The bulk of the people in Kyiv ‘s occupied zone were men. Photographer Anastasia Taylor-Lind, in this interview, talked about what it felt like to be a woman in Euromaidan’s space, which tended to be a pretty macho one given the protestors’ stress on self-defense and the extreme level of violence in the later stages of the Revolution. Her photo book Maidan: Portraits from the Black Square has only a couple photos of women in combat gear. Most of her women subjects are mourners with roses in their hands.

Here’s another contrasting photo by NYT photojournalist Lyndsey Addario who caught four Ukrainian women getting ready for war in 2022. The original photo caption explains that the woman in the middle, who’s crying and looking away from the camera, is a school teacher named Julia. Her anguished expression may stay with you. But come back too to the woman crouching by the door who cradles her gun under one arm as she gazes directly at the camera. Unillusioned but undaunted, doesn’t she look like a lower-case lady liberty?

Passages from an off the beaten path historical narrative by Marci Shore, The Ukrainian Night : An Intimate History of Revolution, speak to the liberating legacy of the months-long occupation of Kyiv’s main square. In the last chapter, one of Shore’s subjects zeroes in on how the Maidan pushed back against “cynicism and mutual mistrust… the two features that distinguish post-Soviet people.” Shore elaborates on that claim, musing about a…

a world where everyone could be bought… Trust was something rare and precious, given and received only among close family and friends, not extending to politicians or writers or priests or neighbors. The Maidan was all the more a miracle in such a society.

Misha Martynenko, another one of Shore’s subjects, amps up the wonder:

‘Astoundingly, on the Maidan… there were very different people—Ukrainians, Russians, Jews, Poles, Tatars, Armenians with Azerbaijanis, there were Georgians, Ukrainian-speakers, Russian-speakers, there were neo- Nazis and liberals and anarchists . . . in the moment of danger everyone united and the differences didn’t matter to anyone. The main thing is that you’re here. It’s not important who you are, it’s important that you’re here, that you haven’t run away.’

Democracy on the Maidan amounted to more than opinions. Shore tells her readers about Vasyl Cherepayn:

‘I am a happy person,’ Vasyl told me: he had now had an experience of real democracy, an experience that most people never have in their whole lives. And despite having been beaten by right-wing nationalists from Svoboda, Vasyl wanted me to know that when he had been there on the Maidan together with members of Svoboda, he had felt safe with them.

Slava Varachuck, the demotic Okean Elzy band leader, gave voice to what deep democracy felt like then and now: “It changed my soul.”

Most Americans are unfamiliar with the history of the Maidan. Perhaps these primary documents will be useful on that score. A people’s revolution anywhere should be a revelation everywhere.

Notes

1 Branko Marcetic. “A US-Backed, Far Right–Led Revolution in Ukraine Helped Bring Us to the Brink of War.” Jacobin, February 7, 2022. https://jacobinmag.com/2022/02/maidan-protests-neo-nazis-russia-nato-crimea.