Michael Walzer’s wise comeback to critics of America’s “forever war” made me think harder about the state of the world’s campaign against Islamist terrorism. Notwithstanding attempts to rope North Korea into the “axis of evil” during W.’s first term, the original “War on Terror” was widely understood to be directed at jihadists who’d declared war on The Great Satan/America in the ’90s and brought it home on 9/11. Walzer doesn’t zero in on Al Qaeda and its offshoots or ISIS; he’s out to underscore the enduring need to combat fanaticism of all kinds. Still, it might be on point to narrow the focus to Islamist terrorism for a moment.

On that front, a line in Walzer’s piece reminds me how much the world—and “secular democrats” (to borrow Walzer’s self-designation)—owes those Kurds who ripped the guts out of an army of terrorists that once seemed like a “strong horse.” Walzer refers glancingly to “the brief campaign against the ISIS caliphate.” He doesn’t mean to slight Kurdish troops who were the boots on the ground in that fight, but I worry (maybe too much?) about diminishing the Kurds’ mighty role in the war against the “caliphate.” I’ve commended Meredith Tax’s A Road Unforeseen: Women Fight the Islamic State here in the past and at risk of hammering on, I want to go back to her account of the siege of Kobane—the turning point in the struggle against ISIS. Tax bowed to women war fighters—one third of Kurdish forces in Kobane were female—but she quotes a male soldier who evokes what it felt like to experience the Kurdish ground zero:

There were dozens of Alamos in that city no one will read about…hundreds of small little battles in small ugly broken houses no one will even care about. It was like Stalingrad. At night it was haunting to see how much of it looked like the moon.

Tax’s reporting backs up that invocation of Stalingrad, though the idea the battle of Kobane was the hinge in the history of ISIS seemed unobvious when she published her book—a season after the incredibly bloody Ramadan of the summer of 2017, when there were ISIS-inspired terror attacks in Baghdad, London, Kabul, Melbourne, Paris and Tehran. ISIS is still able to direct suicide bombings such as the one at a Shi’ite mosque that killed more than forty Hazaras last week in Northern Afghanistan, but it no longer seems to pose a large threat to humanity outside an Islamist nexus. And the decline of this terror-gang began with their defeat at Kobane which deprived them of “their aura of invincibility.” Reporter Michael Weiss has interviewed a former jihadi who told him how ISIS lost five or six thousand fighters at Kobane, most of them foreigners “who had been sent to their deaths without any tactical, much less strategic forethought.” (Thousands more were seriously wounded.) The defeat was devastating for recruitment. Before Kobane, according to Weiss’s informant: “We had like 3,000 foreign fighters who arrived every day to join ISIS. I mean, every day. And now we don’t have even like 50 or 60.”

Walzer takes a long view in his piece on the forever war:

There will be more or less terror at any given moment, just as there is more or less crime—a crime wave and then a sharp drop in assaults and murders; a terrorist “success,” like 9/11, and then a lull.

No doubt. But I hope Walzer’s angle doesn’t lead readers to overlook actors most responsible for the “lull” in ISIS’s terror attacks. The Kurdish-led Syrian Democratic Forces lost 11,000 fighters in the war against ISIS, while America sustained five combat casualties. (In the face of those numbers every American should be permanently shamed by Trump’s 2019 betrayal of our Kurdish allies.)

Another turn in Walzer’s piece suggests he may be less than feelingly responsive to Kurdish heroism because it’s linked in his mind with a historical sequence that began with a bad choice…

[T]his last campaign would not have been necessary if we hadn’t invaded Iraq in 2003 and then left too quickly in 2011 (well short of forever). Iraq in 2003 was actually the first time the “war on terror” was used to justify a full-scale war that had little to do with terrorism.

Walzer cites conflicting rationales for the invasion of Iraq (from a distance as he was a non-believer) and I hear him when he muses: “another argument, for another day…“ Still, I’m not sure his assertion the war in Iraq had “little to do with terrorism” should stand. I remember being moved by arguments for regime change made by Iraqi democrats, but my own mind was made up after I learned Saddam had announced—in the spring of 2002—he was upping payments (to $25,000) to families of Palestinian suicide bombers. Bush et al. didn’t do much to publicize Saddam’s call (or the 2002 Gaza soiree where his minion gave out $285,000 to bombers’ families), but I believed Saddam had to go down once he doubled down on sponsoring terrorism in that post-9/11 period when suicide attacks were the rage in the ummah. I’m recalling just now images from Saddam’s birthday exhibitions back in that day, which featured schoolgirls wearing black face masks of “martyrs” in training.

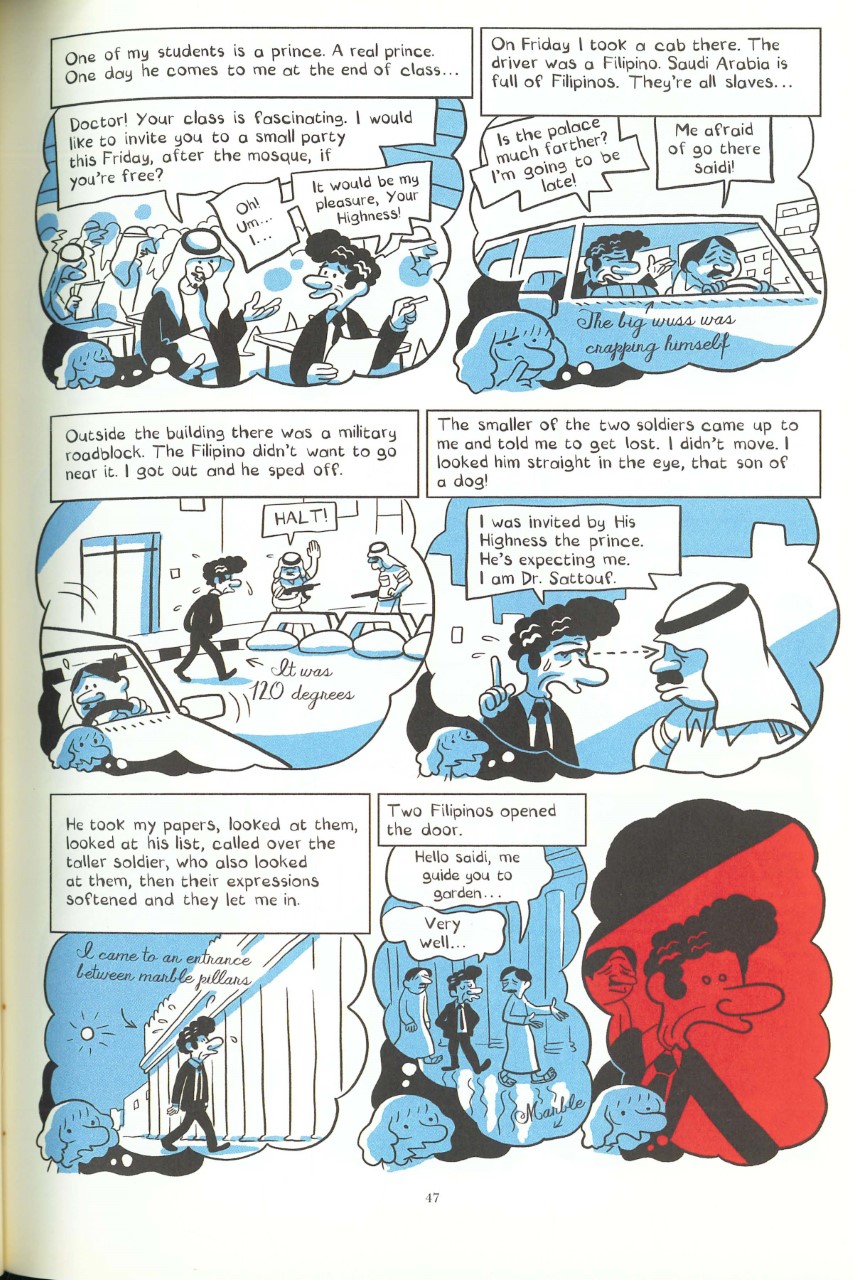

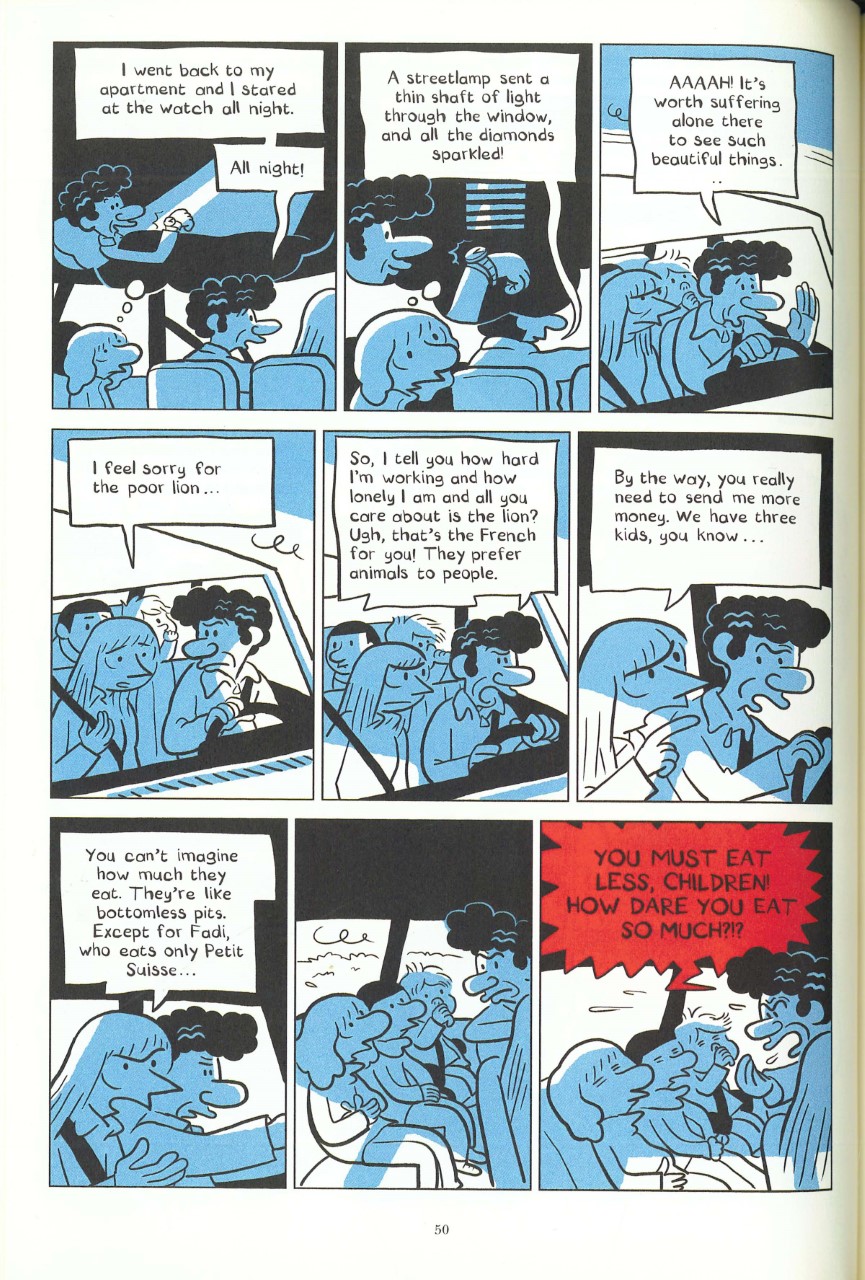

Flash forward to Riad Sattouf’s The Arab of the Future. Walzer affirms the forever war requires an “ideological campaign against religious fanaticism” and that “all of us who talk, write, and argue should be involved.” Sattouf’s multi-volume graphic novel about “a childhood in the Middle East” (which also depicts, without a whiff of sentimentality, interludes in rural France) is a model of the kind of engaged intellection Walzer talks up. Sattouf’s mother—a recessive French woman from Brittany—married a hammy Sunni-Syrian man who moved his family to Libya and Syria in the 80s before going by himself to live in Saudi Arabia. Sattouf’s chronicle tells and shows how he spent hours that felt like ages in the shadows of dictators—Muammar Gaddaffi, Hafez al-Assad—and his own father. Père Sattouf started out in the 70s as a lapsed Muslim who ate pork, drank wine, and enjoyed student life in France. Stuck on “the Arab of the future,” he aimed to be a pan-Arabist modernizer. As he came to spend more time in the Middle East, such “idealism” gave way to grabby Islamism. Not that there isn’t a thru-line to his backward moves. He was always an authoritarian personality who melded Arab supremacism with contempt for “masses.” Prideful, deeply silly with no filter, the father became a meaty subject for his son—a child-artist who took in what was happening in front of his nose (the son, by the way, has a near-Proustian sense of smell)—even if it took decades to process.

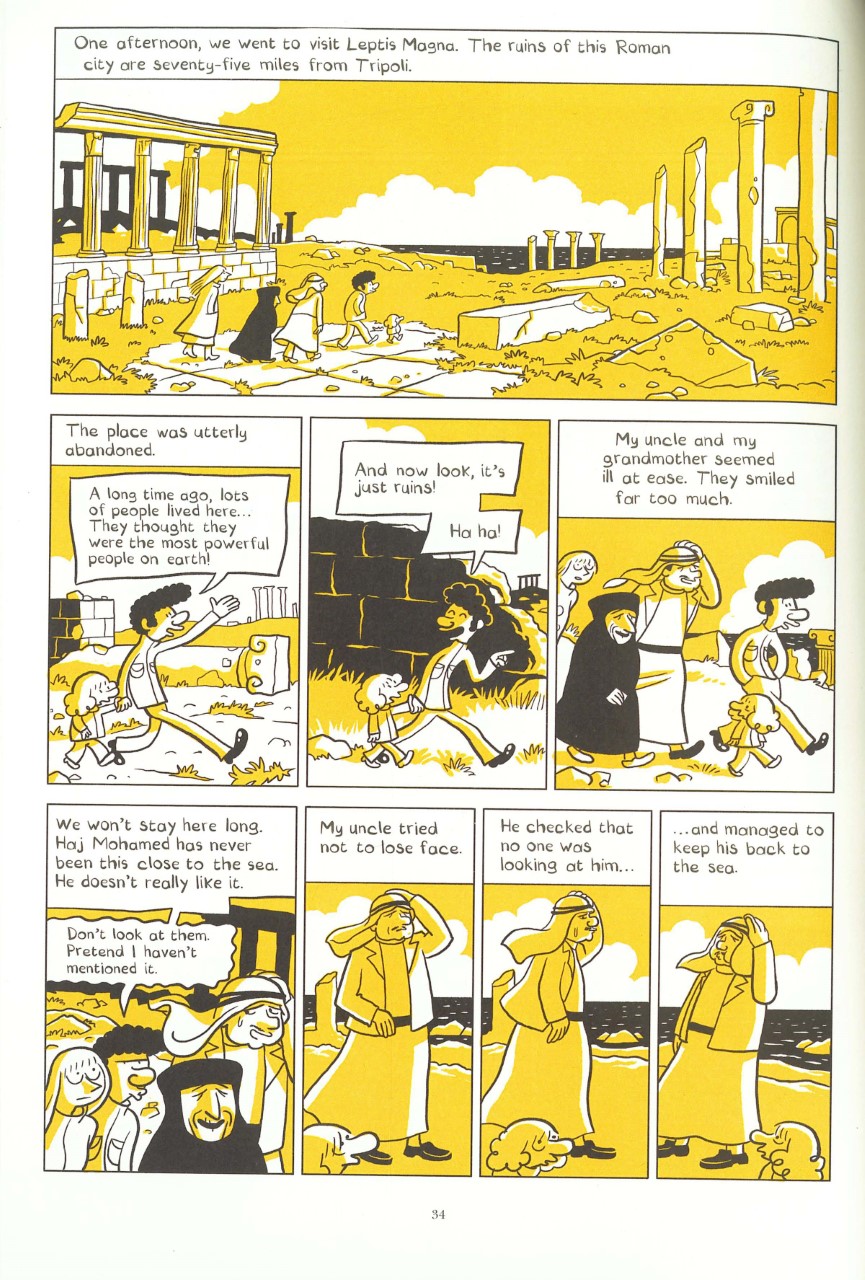

Life with father gave him entry into minds of the benighted in Libya and Syria. And he’s given back images more indelible than, say, a U.N. Index of Development in Middle Eastern States. Try this page from the first volume of his memoir:

Satouff’s visions of Libya and Syria limn the consequences of avuncular not-knowingness and the collective will “to not lose face.” He brings us near sadistic elementary school teachers, bribe-takers, Jew-baiters (who have never met a Jew), dog-and-pony torturers, honor-killers, et al. His wide-eyed views of all-too-human horrors are undeniable. He couldn’t have made this stuff up. That’s why his graphic novel has reached a broad-scale audience in France. (Volume 5 of what’s projected to be a 6 volume set was published there last year.) When it comes to that “ideological campaign” invoked by Walzer, though, the key is to get The Arab of the Future to the next generation of Arabs and Muslims.

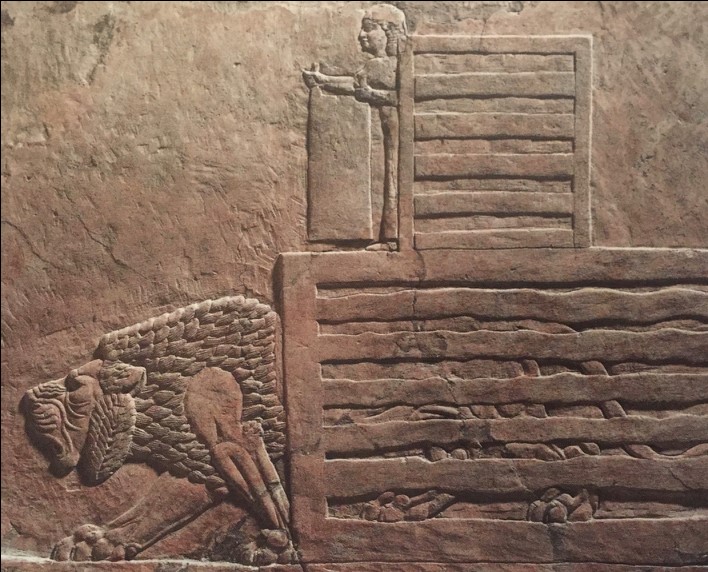

As I paged through the most recent translated volume, it occurred to me Sattouf’s counter-cultural work is in the tradition of a great Mesopotamian artist that Kanan Makiya steered readers to here. Makiya celebrated an anonymous ancient Assyrian sculptor from the seventh century B.C. who put cruelty first among evils—cultivating the uncreated conscience of Middle Eastern peoples. This unknown artist (or artists) carved images of royal lion hunts replicated in the British Museum’s Assyrian galleries. That term “hunts,” however, may be misleading. What’s depicted in the Museum’s copies of the original gypsum and limestone panels was an event where a king displayed his power by killing big cats that had already been captured. The following carving of a little boy opening one lion’s cage before getting back into his own hints at the nature of the spectacle.

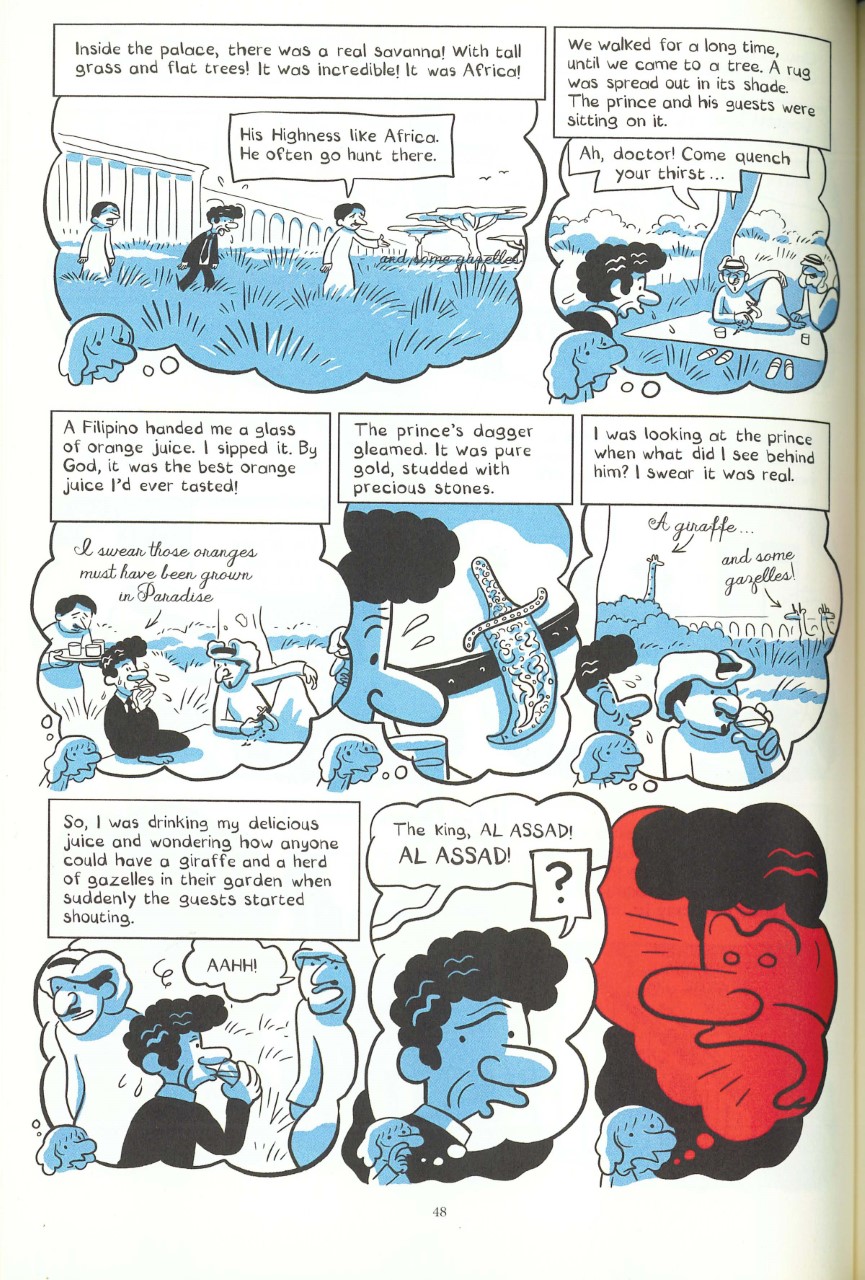

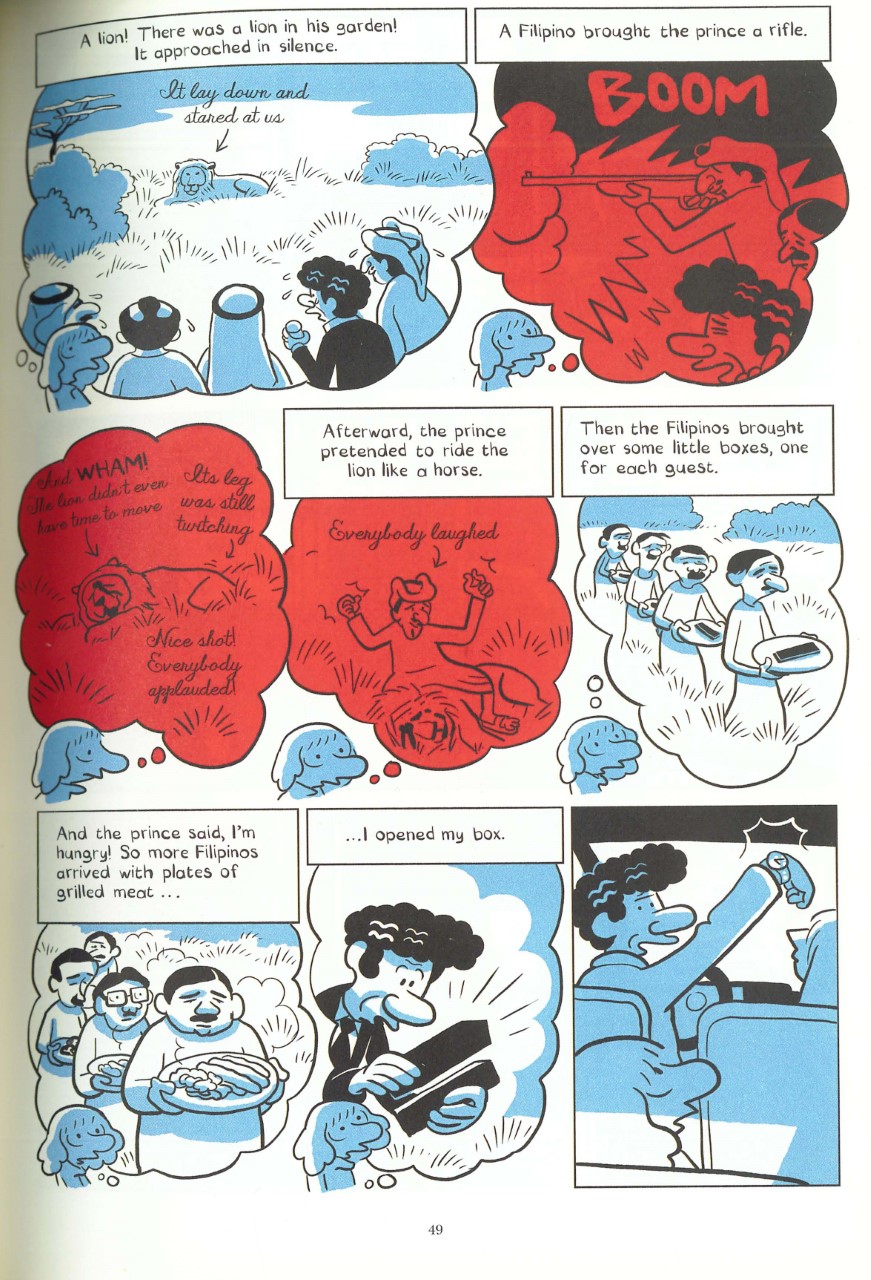

I’m with Makiya when he argues the anonymous sculptor who made the original images of these ceremonies wasn’t neutral about what he witnessed. On the walls of the palace of his master, this outsider artist managed to put up stone protests against a vicious ritual of kingship—protests that are still on time. Just look at the following panels from volume 4 of The Arab of the Future depicting a party hosted by a Saudi prince that climaxes with the killing of a lion (though for Satouff’s greedhead dad, the peak came after the slaughter).

The Arab of the Future provides food for thought to anyone engaged in struggle against Islamists with money and their idolaters.