Dinner on rue de Vaugirard

There was a June evening when Michel and his longtime companion, Daniel Defert, made dinner for us in their rue de Vaugirard flat that began with talk about writing and teaching and about the difficulty of finding good translators. Michel’s I Pierre Riviere, having slaughtered my mother, my sister, and my brother ... had just been published in English and my Leurs prisons had just been published in French; both books had long passages in the demotic. Then we talked about power in government and power in the university and power in other institutions we knew directly: we were all professors, supported by government institutions; Diane had spent years in a convent; and she and I had only a few weeks earlier done field work in an Arkansas prison farm. And Michel’s Surveiller et punir had just been published by Gallimard.

We had met in Buffalo in 1970. SUNY-Buffalo, as it then called itself, was a vibrant place in those years: the faculty was young, energetic and ambitious and there was enough money for interesting visitors who found here a kind of conversation that made many of them want to come back again and again. It was then one of Foucault’s favorite places. It was, in part, what Rio de Janeiro became for him in the next decade: a place to get away from the clutter of Paris and talk to people he liked about things that mattered, a place that was real and important and full of energy and curiosity, place to hang out.

….

Prison work

Michel was an important thinker whose work mattered to my own, but he was also a friend. He wrote the foreword for the French translation of one of my books, In the Life: Versions of the Criminal Experience, translated as Leurs Prisons); he invited Diane Christian and me to the College de France to screen our documentary film, Death Row, and discuss our work; he arranged for us to spend a day at Poissy, a French prison not far from Paris; he helped organize an exhibit of my prison photographs at Galerie Quatorze Juillet in Paris, and accompanied us to and helped us survive the bungled press conference with which it opened.

In the 1960s and early 1970s Michel and I were both involved with prison though for different reasons and in different ways. We both wrote about them. Michel saw prison as a homunculus of social order and I saw it as a way to examine operative culture from the inside and as an occasion for discussing repressive politics from the outside. My writing about the prison world was bifurcated in the American way: in academic pages, I was objective and analytical; in public pages, I was political and often polemical. Michel, in a way that may be especially French, was able to combine all of those modes of discourse. Politics for him was so central an aspect of society was never separable. Our discussions about our different takes on the same structure and process were, I think, mutually informing. Michel knew the historical logic of the world of repression and control far better than I, and I knew the practical aspects of that life in far more detail than he. I learned, in those conversations, that things I considered idiosyncratic and specific were perhaps universal and paradigmatic.

….

Knowing things

He told us that he and some friends had been so successful in their work with prisoners in one French prison that the inmates had, shortly after one of their visits, gone on strike and then had a riot. “And what happened to them next?” I asked him.

What?” he said.

“What happened to them next?” I asked again.

“Their consciousness was elevated,” Michel said, in English.

My question had to do with practical and corporal matters: what did the guards do to the bodies of those prisoners after the famous intellectuals left and took with them their immediate access to the French press? Michel’s answer had to do with the utility of discourse: for him next was a state of perception that broke radically with the state of experience preceding it.

We both knew there was no point carrying this one further, though I doubt either of us knew why. At the time, I ascribed Michel’s abstract response to his naivete. But Foucault was surely not naive.

Then, a year or two later, I ascribed it to his love of talk. Talk is, after all, as basic a French activity and product as the making or drinking of wine. If an American asks another American, ”What were you doing?” and gets for an answer “Talking,” the first American responds, “Talking about what?” I think few French intellectuals would see that follow-up question about topic as at all necessary. We Americans need a subject to justify or legitimize or ratify the encounter, but for the French intellectual, talk can be its own justification and quality of discourse its own ratification; a subject is merely the occasion.

Then I decided that wasn’t it either. I was still trivializing. If Michel wanted conversation, the cafes of Paris offered a more convenient ambiance, and if he wanted merely to utter without interruption, his salle in the College provided a more adoring and attentive audience. Now I think it was his benign pessimism. He knew that few acts of any kind and even fewer volitional acts change anything very much. The radical discontinuities in human consciousness Foucault was so good at revealing were never the results of mere decisions and they were never apparent to the individuals affected by them most directly. The ideas that profoundly intersect our lives make sense later, not before and hardly ever during. He would argue that our individual triumphs are predicated not on mastering the orders that surround and infuse our worlds, but rather on understanding them. We always lose the quotidian battles; all the manipulators of power in all the fields of power Foucault examined were themselves subject to other, manipulators of power; peace and absolute power existed nowhere, and Death, after all, closes all the conversations.

But it isn’t the silences, the denouements of the conversations, that being a sensate and thinking human being is all about. Those prisoners, Michel felt, now better understood the nature of what he perceived as their oppression, what he thought was their condition. Whatever the guards did after the intellectuals went home, the convicts would perforce be happier. If the prisoners saw their condition made better, they would understand the transience and irrelevance of that betterment; if the guards became more brutal, the prisoners would better understand the transience and irrelevance of that marginal increase in brutality. Knowing, he said on another occasion, may not change what is going on; it always changes the meaning of what is going on.

….

Foucault as historian

History is an art based on discovery of the inevitable, and in that regard, for me, Foucault is one of the greatest of historians. He provides a grand logic for moments of inspiration that are otherwise anomalous or flukey or idiosyncratic. It is Foucault, for example, more than any historian of nationalism or any scholar of folklore, who makes sense of the Brothers Grimm.

Foucault points out that it is the discovery of a linguistics of language as spoken rather than the rearticulation of a language as written that ennobles the peasant voices the Grimms elected to record. Grimmsian Nationalism is an application of that transition and perception, not the cause of it. Foucault, in the same extraordinary essay, likewise provides us contexts in which Compte, Marx and Freud become not only explainable, but probable and reasonable.

Scholars in my two academic fields — criminology and folklore — have thus far made little use of Foucault. The anthropologist Clifford Geertz has written intelligently of him (“Stir Crazy,” New York Review, January 26, 1978), but I know few other anthropologists who have been at all comfortable with or receptive to Foucault’s imagination.

Perhaps it is because most scholars in those fields are still very much in the Linnaean phase of development: they are so much involved in the description of behavior and the discernment of categories that they have not yet had time to examine the character of behavior or acknowledge the parochialism of categories.

The part of Foucault’s work I like most and have found most useful is his insistence that we examine things for the order of which they are a part rather than the anomalies they seem to be. “I tried,” he wrote in the foreword to the English edition of Les Mots et Les choses [The Order of Things, 1970] “to explore scientific discourse not from the point of view of the individuals who are speaking, nor from the point of view of the formal structures of what they are saying, but from the point of view of the rules that come into play in the very existence of such discourse.”

In social science — in all the sciences for that matter — limning the odd or exceptional or beautiful is easy. Studies that describe murder or perversion or war or disease are plentiful and unambiguous and often boring. Seeing such things or moments as one with the ordinary is not easy at all. What Foucault did so well was to look at things and say “What is the structure or order in which this makes sense?” rather than “Here’s something odd or peculiar; sit still while I tell you about it.”

….

Seeing things

Foucault is one of the few social analysts whose work regularly unfits readers to continue looking at things or ideas or institutions in the same way. His archaeologies uncover sensible order in what previously seemed sloppiness, incompetence, foolishness, malevolence, or randomness. Foucault insists that the present can never fully explain itself: each moment necessarily incorporates and responds to the detritus of the past, however discontinuous the relationship. If nothing else, as Geertz pointed out, the present moment occupies the space carved and shaped and abandoned by the previous moment.

All our institutions, however deplorable or puzzling their current behavior, make sense, but the secret of the order is not found merely by watching and measuring the institutions as they perform their daily work. Rather, one must carefully uncover the fragments of thought that have made them what they have become. It is hardly surprising that many scholars in the human sciences dismiss Foucault as opaque but in fact find him intolerable and dangerous.

His subject was not the various ways in which we make sense of the world, though he wrote well of those processes, but rather the processes by which we made the World sensible. Not what we thought, but how we thought. He is the historian of the architectonics of facts; not of facts themselves. The prison mattered to Foucault because of what it revealed of the order that required us to have a prison; the discovery of madness mattered to Foucault because of what that discovery implied about the nature of the civilization that needed madness to define itself.

….

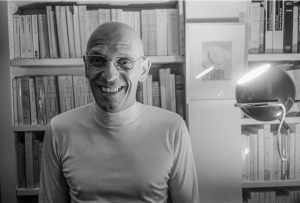

The photo I didn’t take

The photo of Michel I cannot erase from my mind is one I didn’t take. It was when Diane and I were in Paris in 1975 for the exhibit of my Arkansas prison photos at Galerie Quatorze Juillet.

Michel joined us for the opening of the show. One photo in particular caught his attention and he stood looking at it for a very long time. It was a photograph of an old convict with a shrunken face and haunted eyes. I looked at Michel looking at the photo and I was sure he and I were thinking the same thing: If Michel were to get a terrible, wasting disease; this is what he’d look like.

He was a fastidious man; his apartment on Rue Vaugirard was impeccably neat. He and that wasted convict had the same bones. Michel had the flesh; the convict did not.

I had a camera with me. I had taken other photos of him that evening. But I didn’t take that photograph because I was certain he’d guess correctly what I had in mind when I photographed him and that wasted convict. It was like someone in a movie looking into a transforming mirror.

I thought of that moment several years later when a research physician friend called from Paris and said, “Your friend Foucault is in Pitié-Saltpetriere Hospital. Nobody’s admitting it, but they’re pretty sure he’s got AIDS.”

….

The catalogue

Foucault taught us to see how complex institutions incorporate structural imperatives that have become perfectly transparent and therefore invisible; he provided anatomies that reveal how the chords of power with which those institutions are made organize our behavior and perception of the world. He insisted that we understand how our imagination defines the measure and authority of those public and private realities, and that all orders are, finally, orders of the mind, not of the world. In the splendid passage with which he begins The Order of Things, Foucault reminds us of the arbitrariness and transience of all articulated orders. More than any other single passage in his work, the implications of that paragraph have been for me the most useful:

This book first arose out of a passage in Borges, out of the laughter that shattered, as I read the passage, all the familiar landmarks of my thought — our thought, the thought that bears the stamp of our age and our geography — breaking up all the ordered surfaces and all the planes with which we are accustomed to tame the wild profusion of existing things, and continuing long afterwards to disturb and threaten with collapse our age-old distinction between the Same and the Other. This passage quotes a ‘certain Chinese encyclopedia’ in which it is written that ‘animals are divided into: (a) belonging to the Emperor, (b) embalmed, (c) tame, (d) sucking pigs, (e) sirens, (f) fabulous, (g) stray dogs, (h) included in the present classification, (i) frenzied, (j) innumerable; (k) drawn with a very fine camelhair brush, (l) et cetera, (m) having just broken the water pitcher, (n) that from a long way off look like flies.’ In the wonderment of this taxonomy, the thing we apprehend in one great leap, the thing that, by means of the fable, is demonstrated as the exotic charm of another system of thought, is the limitation of our own, the stark impossibility of thinking that.

….

That list

But someone did think it. Borges thought it clearly enough to write it, and Foucault liked it enough to begin his book with it, and I read it and liked it enough to have quoted it in a 1985 talk and several other places since. It is perhaps the single most quoted passage in all of Foucault’s work.

But Foucault didn’t write the passage I quoted. His 1970 Pantheon translator wrote it, presumably based as well as his skill and art permitted on Foucault’s original, Les Mots et Les choses (1966). What Foucault wrote there was:

Les animaux se divisent en : a) appartenant a l’Empereur, h) emhaumes, c), apprivoisés, d) cochons de lait, e) sirenes, f) fahuleux, g) chiens en liherte, h) inclus dans la presente classification, i) qui s’agitent comme des fous, j) innombrables, k) destinésavec un pinceau tres fin en poils de chameau, 1) et cetera, m) qui viennent de casser la cruche, n) qui de loin semhlent des mouches.

The 1970 Pantheon English translation names no translator, and neither the French nor English editions have any notes. Foucault doesn’t say where in Borges’ vast corpus he found that wonderful catalog. I went through all of Borges’ fiction looking for it but I never found it. For years, I wondered whether or not Foucault had made the whole thing up himself. He was capable of that kind of joke.

Then Google came along and in a few seconds I learned that the catalog of animals appears in English in Borges’ essay “The Analytical Language of John Wilkins,” which was included in the book published in English as Selected Non-Fictions (1999):

These ambiguities, redundancies, and deficiencies recall those attributed by Dr. Franz Kuhn to a certain Chinese encyclopedia entitled Celestial Emporium of Benevolent Knowledge. On those remote pages it is written that animals are divided into (a) those that belong to the Emperor, (b) embalmed ones, (c) those that are trained, (d) suckling pigs, (e) mermaids, (f) fabulous ones, (g) stray dogs, (h) those that are included in this classification, (i) those that tremble as if they were mad, (j) innumerable ones, (k) those drawn with a very fine camel’s hair brush, (l) others, (m) those that have just broken a Dower vase, (n) those that resemble flies from a distance.

Those that resemble flies from a distance versus that from a long way off look like flies. There is no comparison in those two translations. They don’t exist in the same verbal universe. That translation, compared to Foucault’s French and the 1990 translation of Foucault, is made of wood.

Borges’ original essay is “El ldioma Analitico de John Wilkins.” It first appeared in book form in Borges’ Otras inquisiciones (1952) thusly:

Esas ambigedades, redundancias y deficiencias recuerdan las que el doctor Franz Kuhn atribuye a cierta encidopedia china que se titula Emporia celestial de conocimientos benevolos. En sus remotas paginas esta escrito que los animales se dividen en (a) pertenecientes al Emperador, (b) embalsamados, (c) amaestrados, (d) lechones, (e) sirenas, (I) fabulosos, (g) penos sueltos, (h) incluidos en esta clasificacion, (i) que se agitan como locos; (j) innumerables, (k) dibujados con un pincel finisimo de pelo de camello, (]) etcetera, (m) que acahan de romper el janon, (n) que de lejos parecen moscas.

Now you know everything anybody else knows about the most famous Chinese encyclopedia in the Western world except one key fact: whether or not it ever existed. Foucault didn’t know that either. Nor, I am certain, did he care.