I was going to start with a question, whether it’s possible to be self-conscious about your hands, but of course the answer is yes. It’s possible, even likely, to be self-conscious about any part of your body, and your hands are right there in front of you every day of your life. Unless you’re asleep, you look at them all day long. Hands are what you do things with from morning to night. You bathe yourself with your hands. They hold the razor you shave with. You use your hands to make your bed. Your hands on the steering wheel guide the car down the road as you drive to work or to the store to pick up some milk and cereal. You eat using your hands. Whatever kind of work you do, from physical labor to taking measurements to cooking to changing the oil in an engine to retrieving files of blood samples to examine them to changing a baby’s diaper to helping an old man or woman in and out of bed to you-name-it, you use your hands.

I have used my hands to type every word I’ve ever written. I used them to write term papers, I typed every letter I’ve written since half-way through typing class during my sophomore year in high school. I typed my first letter to the editor of the Village Voice, the first thing I ever got published. I pounded out every word I wrote for the Voice and for various magazines in hotel rooms on my Olivetti Lettra 22 or on an old Royal typewriter in my office cubicle on University Place and 11th Street. I wrote my first novel, Dress Gray, on an IBM Model D I rented from a typewriter shop – yes, New York had hundreds of them back then – on West 10th Street in the Village. I’ve written every word of every Substack column I’ve published with the hands pictured above.

Someone once asked me if I had ever considered using one of the voice-to-type programs that work on any cellphone, and my answer was no. I can’t imagine writing without typing the words on a keyboard, which means I can’t imagine writing without using my hands.

I’m lucky that I inherited my hands from the Truscott side of the family, because both of my grandmothers were severely arthritic. All of my paternal grandmother’s sisters and brothers in the Randolph family had bad arthritis, with distended knuckles and in old age, cramped fingers. But I got the luck of the draw with my father’s and my grandfather’s hands.

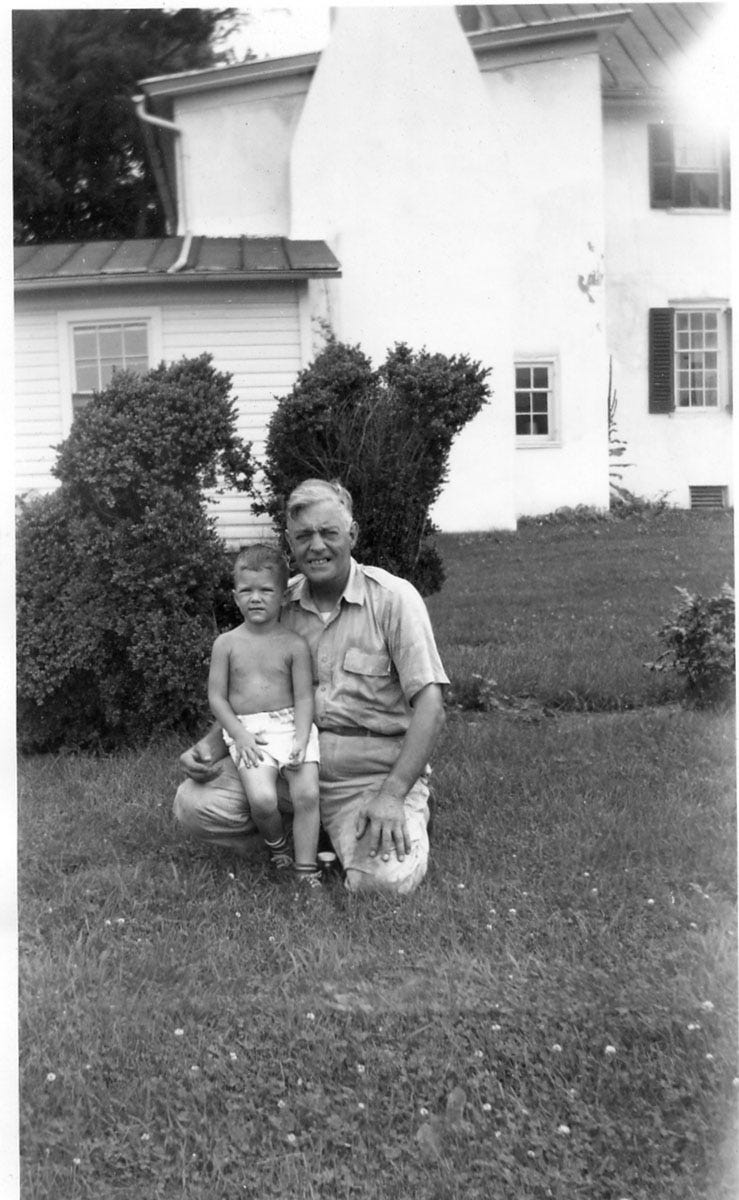

When I say I got my grandfather’s hands. I mean it. This is a photo of my grandfather and me taken at his farm in Loudon County, Virginia, in 1951. I was four years old. Grandpa was 56. Look at our hands: they are mirrored. Our hands are splayed on our thighs, my right and his left. My left and his right are partially closed, like we’re gripping air, on our other thighs. My grandmother posed the photo, stopping me from running around the yard and grandpa from working in his garden – you can see sweat stains in his left armpit and across the top of his left shirt pocket. But she didn’t pose our hands. My hands, and grandpa’s , just fell naturally into those positions, which is eerie, isn’t it? After my grandfather died in 1965, I used to visit grandma in her apartment in Alexandria, Virginia. I don’t think there was a time that we would be cooking together in her little railroad kitchen that she didn’t tell me, “Your hands are just like your grandfather’s.” They were and are: I have his thick fingers and knotty knuckles and broad, flat nails.

In my mind, hands and kitchens go together. I wrote a story for Saveur Magazine once in which I told the story of how I taught myself to cook in my 20’s when I was living in New York and working as a reporter. I think I said something about discovering that you couldn’t eat out much on my Voice salary of $80 a week, so I went over to Brentano’s on Eighth Street and bought a paperback cookbook for 75 cents and taught myself to cook.

But learning to cook wasn’t about eating. As a writer, I lived, and still live, most of every day within my mind, and cooking necessitated using my hands for something other than typing. I’ve always loved the physicality of the kitchen – the chopping and slicing, tying up a chicken with kitchen string and placing potatoes and onions around it in a roasting pan before shoving it in the oven, and then taking it out, golden brown and sizzling, and carving it and arranging the food on plates to serve. I did it with my hands, and it was beautiful, and it tasted wonderful, whatever I cooked – once I learned what I was doing, that is.

I used my hands to build-out my old barge on the Hudson, and in my loft on Houston Street, I tiled the kitchen and framed and put up sheet-rock and spackled and painted walls to build an extra bedroom in the back of the loft. Over the years, I gathered quite a collection of tools, both hand and electric, as I helped to renovate three houses. I built chicken coops in Tennessee with my hands, and I carried feed and broke ice in watering troughs and helped to treat chickens that had been wounded by hawks and foxes. I even crafted tiny splints from stiff wire to straighten the toes of chicks born with cramped feet so they could walk.

Back in the 60’s and early 70’s, you could go to clubs in the Village like the Gaslight and the Café au Go-Go and the Bitter End and the Village Gate and listen to people like Tim Buckley and Phil Ochs and Odetta and Bob Dylan and Kris Kristofferson and John Prine and Doug Sahm and so many others, and you could sit close enough to those little stages that you could see their fingers fly up and down the necks of their guitars. You could see them pick the individual notes of a solo the instant you heard them.

I was always amazed at the ability of musicians to wring such magical sounds from instruments like the guitar and the piano and the saxophone with their fingers, seemingly connected directly to their souls. And then came the day I was describing something in a story – I don’t know what it was, a street, or a face, or even a guitar solo – and I saw my fingers flying across the keyboard creating images and ideas and even arguments, just the way they made music.

It makes me happy to be able to make something with my hands that is sourced from a place within me, because now you can see it with your eyes.