Last season, at the Met, a curator with Dickensian sensitivity to class matters organized a set of eleven Paris prints and watercolors linked to the Manet/Degas show. These pieces—stuck in that odd, tight corridor between the museum’s grand entrance and the European painting wing—were part of New Acquisitions in Context: Selections from the Department of Drawings and Prints. (The title wsn’t the only yawner, who’d stop for New Acq‘s silverware prototypes or “Design for Transeptal Altars”?) The Paris scenes, though, were a trip. So much for peintres celébrès down the hall, Marie-Louise-Pierre Vidal’s watercolors floated viewers into luxe-life while Edgar Chahine’s prints dragged them down and out.

New Acquisitions‘ French array was made up of depictions of Parisian bourgeoisie by French painter Vidal and a range of portrayals (all prints—etchings and lithographs—except for one charcoal sketch) of Paris’s working-class life. Five sets of two pieces, the first three sets had one Vidal and one piece by Franco-Armenian artist Edgar Chahine. The last set had three pieces: two prints counterposed to one Vidal. The sets seem to have been chosen based on their shared content or topic: i.e. food culture, sport/leisure etc. Disjunction, though, was also in the curatorial equation. The aesthetic break between Vidal’s brilliant watercolors and his contemporaries’ dirty monochrome prints was striking. This opposition was made even more trenchant since Vidal and Chahine were contemporaries—Chahine’s works were made between 1904-1908 and Vidal’s images were from 1906-1907. Three pieces by the other French artists in New Acquisitions dated from the late 19th century—and one of them, Paul-Albert Besnard’s Morphinomanes (Morphine Addicts), deserved its own standalone show.

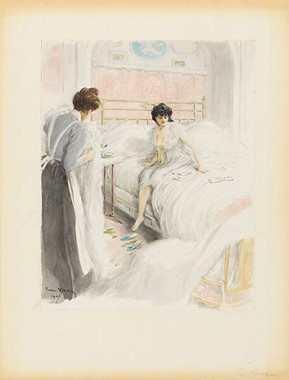

These French pieces were stuck in one nook, right at the entrance to the Met’s Drawing and Prints room. If you started moving clockwise around the corner-exhibit, you began with Vidal’s first scene—a gentlewoman waking up. Her servant peers in through an open door. Her mistress is enveloped in mounds of white fluff. A private moment: the lady’s flowy white nightgown reveals her calves and breasts. Letters, perhaps from a lover, are strewn across her bed—she gazes at these billets-doux, oblivious to her attending maid.

The corresponding print by Chahine ruptured Vidal’s sweet early morning ease. A hunched mattress worker (per the work’s title, Les Matelassieres) labors with a taut rope, and behind her the Seine’s commerce (underworldly and legitimate?) hustles.

Up against Chahine, Vidal’s gentlewoman’s privilege was exposed—her comforts seemed materially and morally corrupt: her soft bedding, a product of an old woman’s hard hands; her relaxation, inextricably tied to those grinding life away.

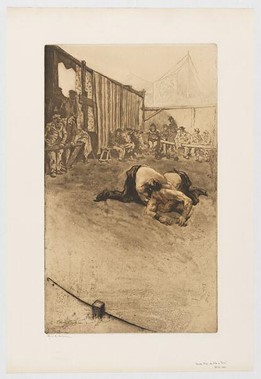

Chahine’s Double Prise de Tete a Terre, came into view next. Two wrestlers grapple with each other in a makeshift outdoor ring. In the background, the working men in the audience (along with a stripper/dancer trying to reclaim their attention?) are cast in a lighter tone than the wrestlers, whose muscled bodies are carefully rendered in sharp, dark detail. It’s clear their physical feats are the focus of the scene.

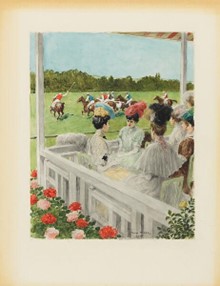

The accompanying Vidal watercolor of a country club offered a multi-hued

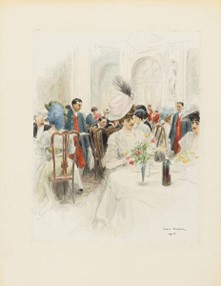

contrast. Polo players gallop on a manicured greensward. In the foreground, their ladies sit primly on the porch. The women’s white dresses have colored accents. Their hairdos are complemented by extravagant headdresses. Here, polite conversation, not physicality, takes center stage.After sporting images, it was on to the distinct food cultures of the Parisian elite and the People. Vidal paints dinner at the Palace Hotel.

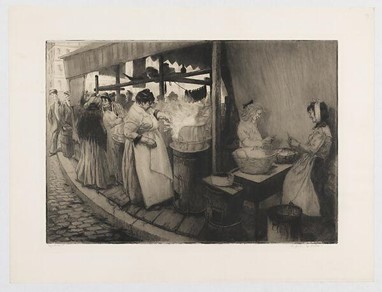

A classical statue looks down on the proceedings. Sharply dressed servants make their rounds. A string band plays it light—nothing to disturb the chatter. Monocles and tight smiles adorn diners’ faces. Perfumes, perhaps, but no scents from food. It’s flowers for dinner? Chahine’s print “Les Frites,” on the other hand, doesn’t make you guess the odor of its surround. In the marketplace, whiffs from a boiling pot of French fries waft off the page. A stately, big lady stirs. The men in line are lucky—those frites have a careful steward, though grease leaks down onto the cobblestones. Sausage hangs from the rafters. Two ladies share a tasty rumor (or deal?). Two other market-women peel more potatoes as the street crowd looks on hungrily.

In the remaining sets, Vidal’s watercolors kept repping the elite, but Chahine’s

work was swapped for prints and sketches by artists/contemporaries Paul-Albert

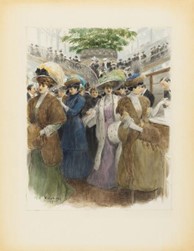

Besnard, Théophile-Alexandre Steinlen, and Léon-Augustin Lhermitte. The contrasts between Vidal’s characters and the figures fashioned by this trio of artists were less precise. The relationship between, for example, Vidal’s posh ladies in Visite aux Grands Magasins and Besnard’s Morphinomanes wasn’t directly oppositional. Side by side with the Besnard’s anti-heroines, though, the gentlewomen seemed as lifeless as mannequins.

They’re encumbered by heavy, pricey fur muffs and wraps. One lady has her free fingers, still in white opera gloves, inspected by a clerk before her next purchase. Vidal’s faddish women are locked on fashion, prior to their outing: brown coat/forest green dress, pink petticoat/green plumed hat are suitable combinations. Eyes dart around the store looking to buy distinction—none of the bourgeois ladies face viewers head on, unlike Besnard’s Mona Lisa.

She’s caught our glance. Long neck turned toward…whoever. Her big eyes look out with an inscrutable self-assurance. Her small intelligent mouth smile/smirks. She takes us in carefully. Besnard etched her sharp nose finely. Behind her, another woman—her features almost indistinguishable—fades into the billowing smoke from a curious vice device. That woman’s slumped body and distraught expression hint she might be coming down. But that First Lady of the demimonde is a mystery. She seems too real to be wearing a morphine mask.

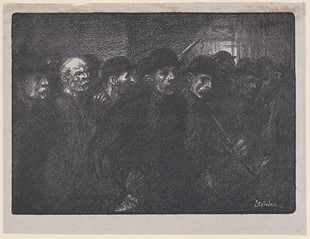

Labor was the last subject of the French batch in last season’s New Acquisitions. Steinlen’s Ouvriers Sortant de L’usine (Workers Leaving the Factory) was subtle, un-didactic. You had to work to make out individuals in the scene’s dark mass.

Workers are “leaving the factory” but Steinlen’s print is no picture of leisure—a dark night awaits. The print could almost serve as an image of the inception of the workday: there’s the light in the distance, open streets or factory flash?

In The Poor Bench in Saint-Germain-des-près, a charcoal sketch that’s nearly as spare, Lhermitte evokes the poor’s compulsory patience.

These two pieces were placed next to Vidal’s Monsieur va au cercle (A Gentleman goes to his club). What fine posture… the sharp creases of his clothes, the well-lit room, the clarity of each shade—the porcelain’s blue vs. the azure carpet’s—make for a harsh opposition to Lhermitte’s and Steinlen’s bold strokes.

…

If you stepped back from the one-on-one comparisons and looked at the sum of Vidal’s works, you might notice his paintings have a dream-like quality. His watercolors’ bottom and top edges are unpainted, unmooring the images. Viewers aren’t brought into the pictures. You’re not made to feel as if you’re actually present inside Vidal’s scenes. At dinner, department store and polo game, uncluttered foregrounds allow viewers to watch his set pieces from a seemly distance. You’re to take in your eyeful and stay in your place.

In the prints of working class life, however, a viewer’s angle isn’t so removed. You are drawn into the action. A pole with a rope rounds the bottom corner of Double Prise de Tête a Terre. This detail—along with the negative space before the wrestlers and the pole, the illusion of distance—marks your inclusion in the audience for the bout. In Chahine’s marketplace, you’re privy to the backstage secrets of the cooking women, but you can’t see everything. The hungry men’s faces fade away as your eye heads down the street that curves back around at the curb, inviting you to step up into the food line. Morphinomanes directly engages a viewer, too—that lady’s glance is all you need from Besnard to feel like you’ve taken the open seat.

A post-Met walk in Central Park made this spectator wonder about a contemporary, local version of the Paris scenes in New Acquisitions. I wished for an exhibit that would address the gulf between the poor and elite New Yorkers’ lives. Looking out from the Great Lawn at Billionaires Row, I was reminded of Andi Schmied’s Billionaire Gabriella persona: the Hungarian artist’s disguise for her art project on Manhattan’s ultra-luxury high-rises. In the long shadows those buildings cast over Central Park, the pitch by one real estate agent—covertly recorded by Schmied—echoed over me:

The walls there are made from silver gold, polished marble of course also from Siberia… this apartment is just unbelievable you will feel Gabriella, it is like going on a journey from the sidewalks of 19th century old New York to the sidewalks of Florence and ending up back in New York. Imagine your daughter… Imagine she would grow up in this apartment, what a wonderful childhood she would have. Imagine the smell… perhaps a goulash—your maid will be getting ready with dinner while you’re just having one of the finest champagnes in a soaking tub with your husband. Imagine waking up every morning to these views.

Imagine, imagine, imagine… Gabriella’s broker is a dealer in dreams—a fantast in the same racket as Vidal with his touches of irrealism. Context/perspective changes but the rich (and their artful dodgers) are never different.