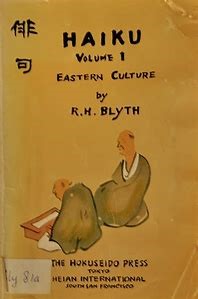

I found the first book of R. H. Blyth’s four volume set, Haiku, (originally published between 1949-1952) in a used book store on St. Mark’s Place. If haiku seems no more pertinent to you than, say, heraldry—one more subject about which even an informed person “need not be ashamed to know nothing”[1]—you may be mollified to hear I had an excuse to check Eastern Culture since I was Christmas shopping for a nephew who’s on his way to Japan this spring. The book’s cover—“Oriental brown simple rough peasant cloth”—got me to open “the Blyth Haiku bibles” (pace Allen Ginsberg, Allen Ginsberg). I fell in…

“Plop!”

To quote the last line of “the most famous haiku” with frog-and-pond as translated by Blyth—scholar-gypsy who brought the East to Beats and Salinger (see J.D.’s bow to Blyth in “Seymour, An Introduction”: “…haiku, but senryu, too…can be read with special satisfaction when R. H. Blyth was on them. Blyth is sometimes perilous, naturally, since he’s a highhanded old poem himself, but he’s also sublime.”) Blyth’s scholarship began to come through to Americans in the post-WWII era—when Japan’s crown-prince was another of his tutees and Blyth helped draft Hirohito’s “Declaration of Humanity.”[2] (He prompted the Emperor to refuse divinity and come out as a mortal though not a Christer as General MacArthur—Japan’s “Supreme Public Administrator”—wished.)

Blyth grew up poor in England, the son of a railway clerk. An outlier from the outset, he was a scholarship boy who loved animals, adopted vegetarianism, and did time as a conscientious objector during World War I. He headed East with his first wife in 1924 after graduating from London University, where he’d been recruited to take a job as a professor of English Language and Literature in Korea. He moved on to Japan in 1939 (with his second wife, a Japanese woman he met in Seoul after his first marriage failed). Interned during the war as an enemy alien, he still managed to begin publishing books in English with a Japanese firm, The Hokuseido Press (who remained his publishers through the Sixties). He ended up working with Japanese and American authorities to help ease the transition to peace after 1945.

Let’s skip out of history and let “Mr. Time-less”—to borrow an honorific bestowed on Blyth by a Zen master.[3]—plump for “plop” in Bashô’s famous haiku, which has also been rendered as “A deep resonance” though Blyth skips over that translation even as he tells why other one-word shots won’t do…

The old pond/A frog jumps in—/Plop!

Against this translation it may be urged that “plop” is an un-poetical, rather humorous word. To this I would answer, “Read it over slowly, about a dozen times, and this association will disappear largely.” Further, it may be said the expression “plop” is utterly different in sound from “mizu no oto.” This is not quite correct. The English “sound of water” is too gentle, suggesting a running stream or brook. The Japanese word “oto” has an onomatopoeic value much nearer to “plop.” Other translations are wide of the mark. “Splash” sounds as if Bashô himself has fallen in. Yone Noguchi’s “List, the water sound,” shows Bashô in graceful pose with finger in air. “Plash,” by Henderson, is also a misuse of words. Anyway, it is lucky for Bashô that he was born a Japanese, because probably not even he could have said it in English. Now we come to the meaning. An English author writes as follows:

“Some scholars maintain that this haiku about the frog is a perfect philosophical comment on the littleness of human life in comparison with the infinite. Such poems are hints, suggestions, rather than full expressions of an idea.”

No haiku is a philosophical comment. Human life is not little: it is not to be compared with the infinite, whatever that is. Haiku are not hints; they suggest nothing whatever.[4]

That isn’t a perfectly representative turn. Blyth tends to stay out of interpretive weeds. He’s not an argufier though he’s given to summative final words: “haiku is the poetry of meaningful touch, taste, sound, and smell; it is humanized nature, naturalized humanity, and as such may be called poetry in its essence.” While he couldn’t help sounding authoritative (or “highhanded” as Salinger has it), he could write light as a feather (like one of his Haiku heroes):

[Kariguro no..Tsuyu ni omotaki..utsubo kano]

…At the hunting place

The quivers are heavy

…With the dewIt is an autumn morning, and something suggests the idea of hunting, perhaps a story or a picture. On their backs is the sinister quiver, arrows with death in every feather. As they pass through the wood, the sun not yet risen, the dew on the leaf and spray wets the quivers, which gradually becomes heavier and heavier. To feel the weight of a thing that has not been touched, has not been seen, that does not exist—this is a greater power than to measure the weight of the moon, or predict the annihilation of the universe.[5]

Numberless light-heavy moves in Blyth’s pages have turned me into a boy again—the one who read favorite books dozens of times. I’m not red-faced at my reincarnation as a re-reader in part because I know I’m not alone. The poet James Kirkup told how Blyth’s stuff worked on him.

I kept on dipping into my four books [of R. H. Blyth’s Haiku], generously illustrated by poem-paintings and painted poems, and I was absolutely entranced. The enchantment came from my apprehension that I was in the presence of deeply cultivated mind that yet bore its remarkable learning very lightly, did not show off its scholarship, but really treated his subject with affectionate familiarity not devoid of a quirky wit. I could hear the man’s voice coming to me from the printed page, a voice both bluff and quiet, common-sensical yet eloquent, plain yet musical.[6]

Anyone can hear the music…

[Ushi shikar koe ni shigi tatsu yube kana]

…At a voice

Shouting at the ox,—

…Snipe rise in the evening..—ShikôThe sun has sunk behind the western hills. All is quiet over the fields. A farmer on his way home suddenly shouts at the ox he is leading. At the sound some snipe rise from the thicket close at hand.

In the quietness of the autumn evening this unexpected occurrence brings out the sound that lurks in silence, the movement in stillness. We feel at the same time the deep, though apparently accidental relation that exists between all things. The ox wishes to stop a moment, and a snipe rises into the air with a whirr of wings. A Japanese poet of two hundred years ago notices this thing, and an Englishman today feels its deep meaning.[7]

That Brit guides you feelingly along “the narrow road to the Deep North” taken by haiku’s originator in the 17th Century. Bashô’s diary of his trip came with poems by him and his votaries. He composed this next haiku while he was detained after a hard climb up to the top of a mountain where he waited out a three-day blow in a frontier guard’s shack.

[Nomi shirami…uma no ryô…makur amoto]

…Fleas, lice,

The horse pissing

…Near my pillow.

Blyth helps you get all of Bashô’s days under the storm…

Yachiro Isobe translates the above verse as follows…

“Harassed by vermin and to hear the staling

of a horse at the pillar,—oh, how disgusting it is!”Bashô’s verse is to be read with the utmost composure of mind. If there is any feeling of disgust and repugnance as a predominating element of mind, Bashô’s intention is misunderstood. Fleas are irritating, lice are nasty things, a horse pissing close to where one is lying gives one all kinds of disagreeable feelings. But in and through all this, there is to be a feeling of the whole in which urine and champagne, lice and butterflies take their appointed and necessary place.[8]

I once tried to walk north with Bashô years ago. (The late Douglas Cushman had steered me there.) But I couldn’t find my way forward. Blyth prompted me to try again. And I got one beautiful reward when Bashô came to the islands of Matushima (though Blyth underscores haiku “does not aim at beauty”: ‘Like the music of Bach, it aims at significance…and some special kind of beauty is found hovering near.”)

The islands are situated in a bay about three miles wide in every direction and open to the sea through a narrow mouth of the south-east side…so this bay is filled with the brimming water of the ocean, innumerable islands are scattered over it from one end to the other. Tall islands point to the sky and level ones prostrate themselves before the surges of water. Islands are piled above islands, and islands are joined to islands, so they look exactly like parents caressing their children or walking with them arm and arm. The pine trees are the freshest green, and their branches are curved in exquisite lines, bent by the wind constantly blowing through them. Indeed, the beauty of the entire scene can only be compared to the most divinely endowed of feminine countenances…

…I noticed a number of tiny cottages scattered among the pine trees and pale blue threads of smoke rising from them. I wondered what kind of people were living in those isolated houses, and was approaching one of them with a strange sense of yearning, when, as if to interrupt me the moon rose glittering over the darkened sea…I lodged at an inn overlooking the bay, and went to bed in my upstairs room with all the windows open. As I lay there in the midst of the roaring wind and driving clouds I felt myself in a world totally different from the one I was accustomed…

I tried to fall asleep, suppressing the surge of emotion from within, but my excitement was simply too great…[9]

Bashô stayed up all night, passing the time reading his Zen friends’ poetry. His invocation of them reminds me of “lonesome traveler” Jack Kerouac’s generous responsiveness to his Beat buddies. While Kerouac wrote On the Road before he read The Narrow Road to the North, Bashô must’ve seemed like one of his homies, especially at the start of his open road (per Blyth’s guide in Haiku):

[Kono nuchi..yuku hito nashi..aki no kure]

…Along this road

Goes no one,

…This autumn eveThis is not sentimentality, nor is it stoicism. There is an unutterable feeling of loneliness which is quite ordinary loneliness with something profounder and not undesirable in its inevitability. In the same way, this road along which Bashô travels alone is the way of Poetry, which to this day, how few there are that tread?[10]

It was Blyth who led Kerouac et al. to Bashô. At a Naropa Institute seminar, Allen Ginsberg recalled that in 1955-6, when he lived together with Kerouac, Gary Snyder, and Philip Whalen in a cottage in Berkeley, they were all constantly referring to Blyth’s “fantastic anthology with all the great historic haiku.”[11]

Kerouac’s The Dharma Bums (1958), with its character Japhy Ryder (based on Gary Snyder) caught mid-50s American Zen on the come in this famous passage…

A world full of rucksack wanderers, Dharma Bums refusing to subscribe to the general demand that they consume production and therefore have to work for the privilege of consuming, all that crap they didn’t really want anyway. . . I see a vision of a great rucksack revolution, thousands or even millions of young Americans . . . all of ’em Zen lunatics who go about writing poems that happen to appear in their heads with no reason and also being kind and also by strange unexpected acts keep giving visions of eternal freedom to everybody and to all living creatures.

I doubt Blyth meant to amp up America’s Zen boom, though he certainly shared the Beats’ anti-careerism—“true poetical, religious life can never, by any accident, lead a man to an archbishopric or a baronetcy.”[12] You know he was born on the wrong side of tracks (like Ginsberg, Corso and Kerouac?) when he presents haiku by Issa:

[Yoigoshi no..tofu akari ni..yabuka kana]

…The bean-curd of last night

Gleams whitely

…Striped mosquitos hoverIssa is the unromantic poet…“The moon gleams whitely,” “flowers of the pear-tree gleam whitely,” this we know and approve. But the bean-curd put in the water in a bowl the night before is Issa’s poetical food. In the early morning, before the sun has risen, Issa goes to the kitchen and sees the milky-white bean-curd glimmering in the twilight of the room with its blackened walls and ceiling. A few yabuca, thicket mosquitos hover round the bowl, their long-striped bodies clearly outlined. This moment is the real poetic life, the life of haiku.[13]

The poetic life of unfledged Issa always goes straight to Blyth’s heart:

…The young child,—

But when he laughed,

…An autumn evening—The child was the boy, Kinzaburo, a year old, left by Issa’s first wife Kiku, when she died in 1823; four or five young children had already died. A prescript says, “A motherless child learning to crawl on the tatami.” In the midst of his herculean efforts to advance an inch or two, he suddenly looks up and laughs—with his dead mother’s laugh:

O Death in life, the days that are no more!

Is it not too heartrending for poetry? Down it must go in black and white like all the rest. And in the last line, autumn has come, the world rolls on, life and death in endless succession. Life is suffering.[14]

With a breeze…

[Gege no..gege gege..no gekoku no..guzuahisa go]

…Poor, poor, yes, poor

The poorest of the provinces,—and yet,

…Feel the coolness!The original is a masterpiece, not of poetry, so-called, but of life. The sound of ge repeated seven times, is like hammering Issa down in the coffin of his poverty, a poor man in a poor village of a poor province. But from the pit of poverty he cries, “How cool and pleasant the wandering airs come to us!”[15]

I didn’t identify Blyth’s English temper with cool Beats when I first dipped into Haiku. His exactitudes reminded me of F. R. Leavis, though Blyth had more humor and liked to dance on the page rather than come across as a warrior-critic or wannabe hammer-of-the-canon. Blyth trusted D.H. Lawrence’s gut almost as much as Leavis (who heroized Lawrence). Blyth leans on passages like this one from Lawrence

Life and love are life and love, a bunch of violets is a bunch of violets, and to drag in the idea of a point is to ruin everything. Live and let live, love and let love, and follow the natural curve, which flows on pointless.

when he’s out to evoke the Way of Zen. But Wordsworth was Blyth’s British avatar. He devotes the penultimate chapter of his first book, Zen in English Literature and Oriental Classics (1942) to Wordsworth. (He limns “the Zen of Shakespeare” brilliantly in the next and last chapter.) Wordsworth is also a major presence in the chapter, “Poetry is Everyday Life,” from Zen in English Literature I’ve reprinted/posted here.

Wordsworth’s gravity for Blyth can be grasped from his list of “great men,” which he gives in one of his volumes on Zen and Zen Classics: “I myself would choose in this order, Bach, Bashô, Thoreau, Unmon, as the first four, with Shakespeare, Mozart, Wordsworth, Eckhart, Pô-Chu—and others following.”[16] Wordsworth is the Anglo One for Blyth when it comes to his trinity: poetry is everyday life; religion is poetry; love of nature is religion.

Blyth underscores the radicalism of Wordsworth’s refusal to abide by the rule—upheld from “Aristotle down to Arnold”—that a “great subject was necessary to the poet…

Arnold says that plot is everything. It is useless for the poet to “imagine that he has everything in his own power, that he can make an intrinsically inferior action equally delightful with a more excellent one by his treatment of it.”

Wordsworth stands outside this tradition by instinct and choice. He chooses the aged, the idiot, the vagrant, but does not endeavor to make them “delightful” at all.[17]

Wordsworth’s dailiness, like haiku’s, is sacred and democratic:

Even to the loose pebble along the highway, he “gave a moral life,” but he does not fall into moralizing about nature. In the poetry of Wordsworth and that of haiku there is this seemingly unimportant but deeply significant common element: that the most ordinary people, those to whom Buddha preached and Christ died, are able, if they will, to understand it.[18]

In Blyth’s maps of Zen in English and Oriental letters, he often points to lines in poems such as “Tintern Abbey” where Wordsworth inhabited “the true region of haiku.” To Blyth, passages like this graceful one echoed and rolled like haiku’s natural grooves.

………………………………….And I have felt

A presence that disturbs me with the joy

Of elevated thoughts; a sense sublime

Of something far more deeply interfused,

Whose dwelling is the light of setting suns,

And the blue sky, and the mind of man:

A motion and a spirit, that impels

All thinking things, all objects of all thought

And rolls through all things

Yet Blyth realized Wordsworth was on anything but a roll as the author of “There was a Boy” went down from innocence, passing “from Zen through Pantheism to Orthodoxy.” Blyth recalls how Wordsworth once had little time for “Jehovah—with his thunder and the choir/Of shouting angels and the empyreal thrones” before tracing his later recantation in less inspired trips like “The Excursion”:

That the procession of our fate, howe’er

Sad or disturbed, is ordered by a Being

Of Infinite Benevolence and Power

Whose everlasting purposes embrace

All accidents converting them to good

Blyth believed in forbearance, but he wasn’t about to put up with late Wordsworth’s dead dogma. You can sense the heat of a former conscientious objector as Blyth lays out how “this doctrine reached its logical and imbecilic conclusion in the Ecclesiastical Sonnets, Forms of Prayer at Sea…

…where we are told that the crew, saved from shipwreck by God, are right to give solemn thanksgiving for His mercy (but how about those who were drowned, or died of thirst in an open boat?) and that English sailors will always win naval battles if they ask God to assist them.

“Suppliants! the God to whom your cause ye trust

Will listen, and ye know that. He is just.”All this kind of thing comes from the intellectual separation of God and man and nature. A separation of man from Here and Now. Wordsworth says

“Our destiny, our being’s heart and home,

Is with infinitude, and only there.” (Prel. VI, 604)It is not. Take no thought of the morrow, or for infinity or for eternity. Take no thought of what will happen five minutes afterwards, one minute afterwards. Blessed are the poor in spirit now! Nama Amida Butsu, NOW![19]

Blyth invokes here the primal vow of “Pure Land” Buddhists: “to save all suffering beings EVERYWHERE.” Blyth was a practicing Buddhist. One of his mentors was D.T. Suzuki—the scholar who went on to be instrumental in spreading interest in Zen (and Far Eastern philosophy in general) to the West in the 50s and 60s. Blyth dedicated one of his books to Suzuki but he was never a suck-up. He held back when Suzuki’s readings of haiku seemed too schematic: “The danger of [Suzuki’s] view is that it makes the poem stink of Zen.” Whiffs of abstracted piety always put Blyth off. (He once gave a lecture titled “Why I Hate Buddhism.”: “He explained this disconcerting statement by saying he hated anything ending in ‘ism’…”)

I don’t believe he ever spelled out details of his own spiritual exercises, though he took his Zazen seriously and got deep into Buddhism’s back story. In Volume One of his Zen and Zen Classics, he traced the history of Zen from 1000 B.C. to 715 A.D. and then explicated great treatises on Zen, such as Chengtaoke (Song of Enlightenment). Per David Cobb et al. of the British Haiku Society, Blyth is at his most “insolently, amusingly brilliant, and absolute master of his material.” I’ll take the Society man’s word. I’m still trying to get my mind around Blyth’s chapters in Zen in English Literature and Oriental Classics on “Paradox” and “The Pale Cast of Thought.” Blyth shines there because he does in scholasticism without talking up mindless vitalism. He begins by citing greatest hits against intellect by “writers of all kinds” and ends with his own critique of reason. (He locks on Tennyson’s meld of faith and faux-consecutive thought as he traces how intellection usurps “the imagination, the compassion, of the poet…

It is particularly detestable in, for example, Tennyson’s

“Faith hears the lark within the songless egg.”

One would like to read some lines on a maiden asleep on a pillow stuffed with the feathers of the lark which would have come out of the egg only someone ate it. This is not poetry at all. It is a kind of proleptic vivisection.[20]

In between, though, he crosses you up (like a Zen teacher?), playing a wise guy as well as wise man…

All this [poets’ refusal of reason] begin to make one think there must be something good about the rational power, if it can stir up such indignation. It is hard for a rich man to enter into the Kingdom of Heaven, but it is also hard for a fool. Is it a coincidence that Christ and Buddha had extremely powerful and subtle intellects? Christ could quibble with best of the Jewish Sophists, when necessary. And when we consider the case for Blake himself, is it not a fact, that, despite his mysticism and poetry and painting, his chief defect was, not being a genius or mad, but that he was a bit of a fool? To paint pictures which everyone can understand and write poems which nobody can make head nor tail of without an answer book, argues lack of ordinary foresight. We do not find people like Inge or Shaw despising the reasoning faculty because they have it. The essence of it, of course, is the power of comparison and the power of self-criticism. It is the scissors and pruning hooks of the mind, without which no work of art, in its symmetric perfection, can be produced. Blake himself illustrates this in, for example, the composition of such a poem as the “Tiger,” (see the Oxford “Blake,” pages 85-88) with all the different drafts and alternatives. This is a parable of our own lives, and the relation of the intellect to Zen. Just as

…The Law was our schoolmaster to bring us to Christ,

So the intellect leads us to Zen.[21]

Though the thingness of things matters even more for haiku:

[Hiya-hiyato.. kabe wo fumate..hirume kana]

…A midday nap;

Putting the feet against the wall,

…It feels cool...—BashôEven on the hottest day, if we put our bare feet against the wall when we are lying down, it feels cool. If you ask where the poetry is in this verse, we can only answer there is a contact with things here that is of the essence of poetry. It needs, however, a great effort to work up in the mind this experience of physical coolness into one’s own poetical life…

In Blyth’s Haiku, Bashô’s wall—and nap—leads to Issa’s…

[Motaina ya..hirune shite kiku..taue]

…In my mid-day nap,

I hear the song of the rice-planters,

…And feel somehow ashamed of myselfAll those who work with the head only must have had this kind of uneasy feeling, an unreasonable thought of the inferiority of mental labor compared with that of the engine-driver or carpenter. There is the Buddhist story of the farmer who accused Buddha of idleness and was told, “I scatter seeds of faith” and so on, but we cannot help thinking that the farmer was talked into silence but was not convinced. Issa’s feeling is a just one. Every man must do a certain amount of physical labor every day, or suffer spiritual consequences.[22]

“Materiality” makes Eastern Culture’s list of thirteen ways-words that define “the state of mind which the creation and appreciation of Haiku demand…”:

.1. Selflessness.

.2. Loneliness.

.3. Grateful acceptance.

.4. Wordlessness.

.5. Non-intellectuality.

.6. Contradictoriness.

.7. Humour.

.8. Freedom.

.9. Non-Morality.

10. Simplicity.

11. Materiality.

12. Love.

13. Courage.[23]

Blyth zeroes in on Bashô’s state of mind and character when he muses on how this ex-samurai came to invent a new poetic vocation. He points out there were other Japanese poets, “lesser men,” who were composing “good haiku” at the same time as Bashô, yet “they did not have the modesty, the generosity, the ambitionlessness of Bashô…

When we call Bashô the greatest of the (haiku) poets of Japan, it is not only for his creation of a new form of human experience, and the variety of his powers…He has an all-round delicacy of sympathy which makes us near to him, and him to us. As with Dr. Johnson, there is something in him beyond literature, above art, akin to what Thoreau calls homeliness. In itself, mere goodness is not very thrilling but when it is added to sensitivity, a love of beauty, and poetry, it is an irresistible force which can move immovable things.

In his chapter on Bashô in Eastern Culture, Blyth chose a dozen or so verses to illustrate the poet’s variousness. This one came under the heading of “Delicacy”:

[Chimaki musubu..katate ni hasamu..hitai-gami]

Wrapping rice dumplings in bamboo leaves,

With one hand she fingers

The hair over her forehead.

Where Bashô is at his greatest, per Blyth, is where he seems most insignificant, that strand of hair wrapped around her finger…

the neck of a firefly, hailstones in the sun, muddy melons, leeks, a dead leaf,—these are full of interest but not as symbols of the Infinite, not as types of Eternity, but in themselves. Their meaning is just as direct, as clear, as unmistakable, complete and perfect, as devoid of reference to other things, as dipping the hand suddenly into boiling water. The mind is roused like a trumpet…it is just like suddenly seeing the joke of something. It is like suddenly being unexpectedly reprieved from a sentence of death.[24]

Blyth rises up for Bashô’s rousing refusal of fine distinctions between the “poetical and unpoetical subject” in the “Poetry is Everyday Life” chapter of Zen in English Literature and Oriental Classics.

The sound of someone

…..Blowing his nose with his hand;

……….The scent of the plum flowers!The sound of the nose-blowing, the scent of the flowers, which is more beautiful? The first may remind us of a long-lost, beloved friend; the second, of the death of a child who fell from the bough of a plum-tree. Beethoven may have got the motif of the first movement of the Fifth Symphony from someone’s blowing his nose. Underneath all our prejudices for and against things we must be free of them. This same freedom from the idea of dignity, that there are vessels of honour and vessels of dishonour, is shown in the following, full of life and truth:

Look! The dried rice cakes

…..At the end of the verandah—

……….The uguisu [bird] is pooping on them!More certainly than many things written in the Gospels, Christ went to the lavatory. This action was no less holy and no more symbolical than the breaking of bread and the drinking of wine at Last Supper. Wherever bread is eaten, Christ’s body is broken. Wherever wine is drunk, His blood is shed…

Easter, 2024 ……….

Part 1 (To Be Continued)

Notes

1 Per Disraeli.

2 “Blyth had his first meeting with the Emperor Hirohito on February 14, 1946…[H]e was able to present to the Emperor…a copy of The British Royal Family in Wartime. This popular publication was a photographic record of the activities of King George VI and Queen Elizabeth, when they visited bomb sites and air raid victims and shelters in the London Underground. In this way, Blyth was instrumental, always through intermediaries at court, in persuading the Emperor, who until war’s end had been reverenced as a deity, to undertake a journey all over Japan (excepting Okinawa) to show himself as an “ordinary mortal.” On p. 8 of James Kirkup’s introduction to The Genius of Haiku: Readings from R. H. Blyth on poetry, life and Zen.

3 D. T. Suzuki’s jokey translation of “Blyth” into Japanese. On p. 18. (and the back cover) of The Genius of Haiku: Readings from R. H. Blyth on poetry, life and Zen.

4 R. H. Blyth: Zen in English Literature and Oriental Classics, Chapter 15.

5 R.H. Blyth: Haiku, Volume III Summer/Autumn – “Sky and Elements: ‘Dew.’”

6 James Kirkup, introduction to The Genius of Haiku.

7 R. H. Blyth: Haiku, Volume III Summer/Autumn – “The Long Night.”

8 R. H. Blyth: Haiku, Volume III Summer/Autumn – “Birds and Beasts: ‘Lice.’”

9 Matsuo, Bashô: The narrow road to the Deep North and other travel sketches.

19 R. H. Blyth: Haiku, Volume III Summer/Autumn – “Autumn Evening.”

11 https://allenginsberg.org/2013/09/spontaneous-poetics-129-blyth-haiku/ Ginsberg is quoted: “Blyth’s books are a fantastic anthology of all the great historic haiku by Issa, Basho, Buson, and others. Issa I like particularly, as being similar to William Carlos Williams, as an objective subjectivist [sic]… They give you the Japanese writing script (writing, or whatever you call it), then they give you a transliteration (so you get the sound), then they give you a very good English translation, then they give you an explanation of all the private Japanese references, and show(ed) how it relates to the seasons…”

12 Blyth was hard on his Korean students who resisted his classroom manner when he started out in the 20s. (“I lacked humility.”) But James Kirkup avers he was “definitely a man of the people, and no snob, though he may have been tempted to be one, for one of his students saw, pinned to the wall of his study, this motto: ‘Not to be sentimental. Not to be cruel. Not to be selfish. Not to be snobbish.’”

Kirkup concedes: “One does not give oneself that kind of admonition without some reason.” No doubt Blyth must’ve had a sense he hadn’t wasted what he once termed (in an autobiographical fragment) “my one and only life.”

13 R. H. Blyth: Haiku, Volume III Summer/Autumn – “Birds and Beasts: ‘Mosquitos.’”

14 R. H. Blyth: Haiku, Volume III Summer/Autumn – “Autumn Evening.”

15 R. H. Blyth: Haiku, Volume III Summer/Autumn – “The Coolness.”

16 “The order is the order of Zen”

17 R. H. Blyth: Zen in English Literature and Oriental Classics, Chapter 27.

18 R. H. Blyth: Zen in English Literature and Oriental Classics, Chapter 27.

19 R. H. Blyth: Zen in English Literature and Oriental Classics, Chapter 27.

20 R. H. Blyth: Zen in English Literature and Oriental Classics, Chapter 12.

21 R. H. Blyth: Zen in English Literature and Oriental Classics, Chapter 12.

22 R. H. Blyth: R. H. Blyth: Haiku, Volume III Summer/Autumn – “Mid-day Nap”

23 R.H. Blyth: Haiku, Volume 1, Eastern Culture, Section 2.

24 R. H Blyth: Zen in English Literature and Oriental Classics, Chapter 3.