Paul Krassner, 9 April 1932—21 July 2019

Paul Krassner was one of the funniest and most irreverent people I ever knew. In 1958, he created one of the great satirical political rags, The Realist, all 146 issues of which are online (http://www.ep.tc/realist/index.html) . He was one of Ken Kesey’s Merry Pranksters and, along with Abbie Hoffman and Jerry Rubin, a founder of the Yippies (the name was his idea). He wrote all the time. His books had titles like Tales of Tongue Fu (1981) and One Hand Jerking: Reports from an Investigative Satirist (2005). He edited the autobiography of his friend Lenny Bruce, How to Talk Dirty and Influence People (1965).

My two favorite memories of him center on one-line in-the-moment gags.

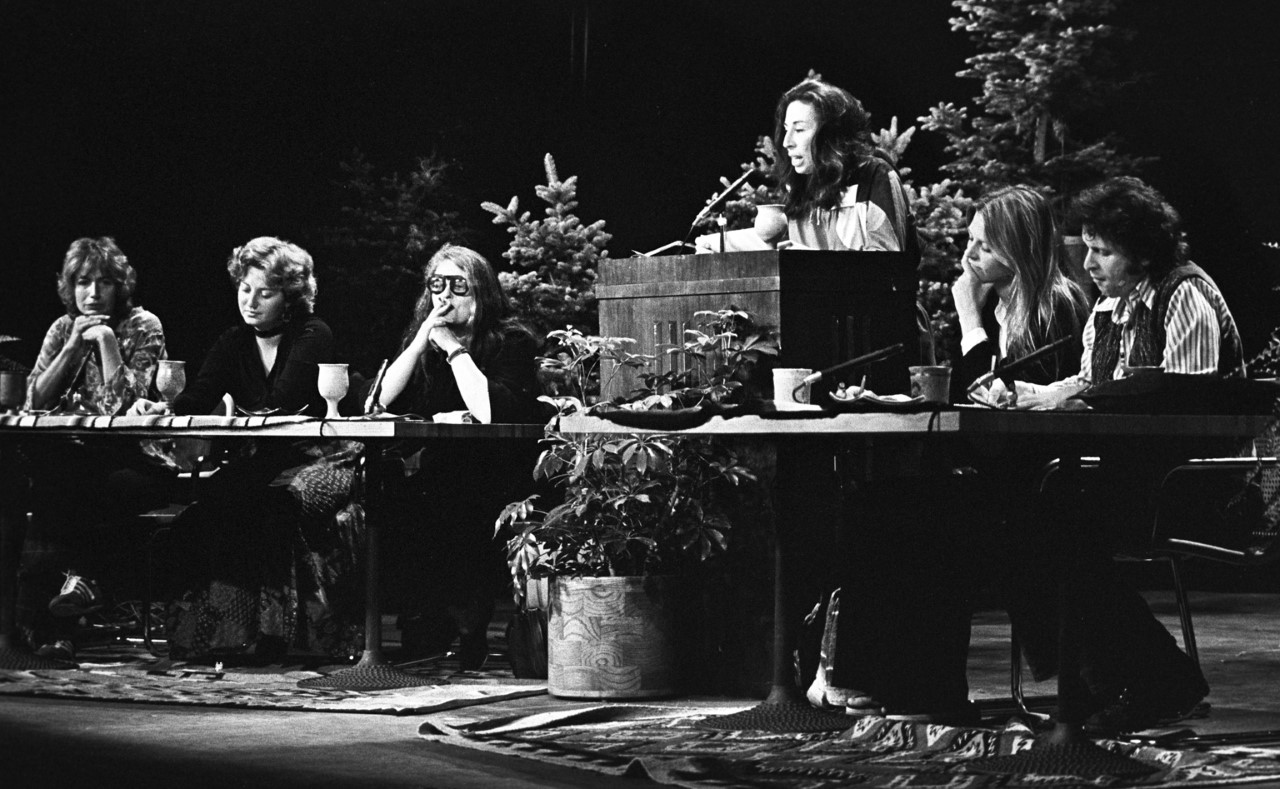

At the 1978 Institute of the American West conference, The American Hero: Myths & Media, he was on a panel responding to a talk by Diane Christian titled, “Wonderwomen: Superheroines of American Popular Culture.” The panel was moderated by actress Lindsay Wagner (then star of the TV series “The Bionic Woman”). The other panelists were actress Penny Marshall, feminist author Kate Millett, and director Doe Mayer. The discussion was lively and ranging.

When Wagner asked Paul if he’d like to say anything, he shrugged and said, “Only that I’m suffering womb envy.”

A few years earlier, we’d been at a drug conference in Hampton Bays, Long Island, organized by the National Student Association. The hotel was a rambling Victorian place with stairways everywhere. There was also a newer annex. The organizers put everyone they thought was square—judges, psychiatrists, etc.—in the annex. The organizers and the people they thought not-square were in the big old building. The organizers told the people they thought square that they were getting more comfortable, more modern digs. The implication was that those who were older and better-known were getting deferential treatment. That wasn’t the reason at all. After the respectable folks went off to their better digs, the people from NSA distributed what they proudly said was fresh Owsley acid—the best LSD connections could get and money could buy.

Sometime later, I found myself in a room with three beds and five people. Paul was one of them. It was a drafty summer hotel, not built or modified for winter use. The room was so damp and cold we all went to bed with our clothes on, including jackets and sweaters, and we covered ourselves with whatever blankets we could find. My bedmate was a woman I hadn’t spoken to before the moment we decided who would get which side. She chose the side against the wall.

I woke in the night and went to the window. Outside, violent white surf was raging very close to the hotel. It was beautiful in the moonlight. I knew that the acid might interfere with my memory of that night, so I made a note describing it in detail. My ball-point pen had the amazing ability to write in four different colors, which I hadn’t realized previously. I didn’t choose the colors; the pen did it.

I went back to bed and slept a while. When I next woke, the window was just going slate-grey. I looked at my watch and said, “My god! It’s twenty to six.” Across the room, Paul peeled the blanket off his face and said in a perfectly even voice, “Bruce, those are shitty odds. Go back to sleep.” Then he disappeared under his blanket.

When I got up, I went to read my brilliant polychrome note from the night. The page was covered with an unintelligible scribble, all of it black. I went to the window to see what the surf was up to. There was no surf in sight: just the hotel parking lot and a distant highway. On the way down to breakfast, I told Paul about the disappearing surf and transiently-magical pen. He said nothing. I’d later come to realize that in the world of Owsley, which Paul knew infinitely better than I ever would, a hallucination consisting of surf in a parking lot and a pen with its own ideas about color was barely worth mention.

My Buffalo English department colleague Leslie Fiedler, in his dotage, would sometimes tell stories about when he, Philip Roth, Amiri Baraka, Paul Krassner and I all lived near each other in the Weequahic section of Newark. Amiri never lived in that part of town. I don’t know if Paul ever lived in Newark at all. Roth, Amiri, Leslie and I had, but never at the same time. The only neighborhood boy Leslie left out was Jerry Lewis, who wasn’t there at the same time either. It didn’t matter to Leslie: toward the end, he folded all of us (except Lewis) into his stories of growing up.

Paul had the worst complexion of any adult I ever met: more zits than a teenager’s worst day. That probably explains the piece of tissue paper on his cheek in the photo I took during the 1978 Sun Valley conference.

He was, as I noted above, one of the funniest people I ever knew. But when he was writing, he wasn’t just making gags: his work always had an edge, which is why people who weren’t very amused by him often got very pissed off at him. It is also why so much of what he wrote is fun to read all these years later. And that is why the disembodied finger pointing at him in the photo seems perfectly appropriate.

P.S. Author’s photo of the IAW event with (L.to R.) Marshall, Mayer, Millet, Christian, Wagner, & Krassner.