“Culture is about the rules; Art is about breaking them.”

JLG by JLG

Filmmaker Joel DeMott died from C.O.P.D. in Montgomery on June 13th, watched over by her longtime partner, Jeff Kreines, who never left her side during her seven-week stay in the hospital. Jeff was the calmative One, holding her hand when her oxygen got low, willing her to breathe mindfully. My sister Megan and I were there too at the end. I cued up a few tunes from YouTube on the evening of the day but Jo wasn’t able to communicate by then so there was no way to know if she wanted songs or silence. Once “Blue Eyes Crying in the Rain” segued into “Have You Been Making Out Okay?” I quit playing DJ. The algorithm took over then—Al Green’s “Funny How Time Slips Away” came on unbidden and it broke Jeff down, not that he hadn’t been crying off and on all week. Still, as he mused later, the sequence was very verité…

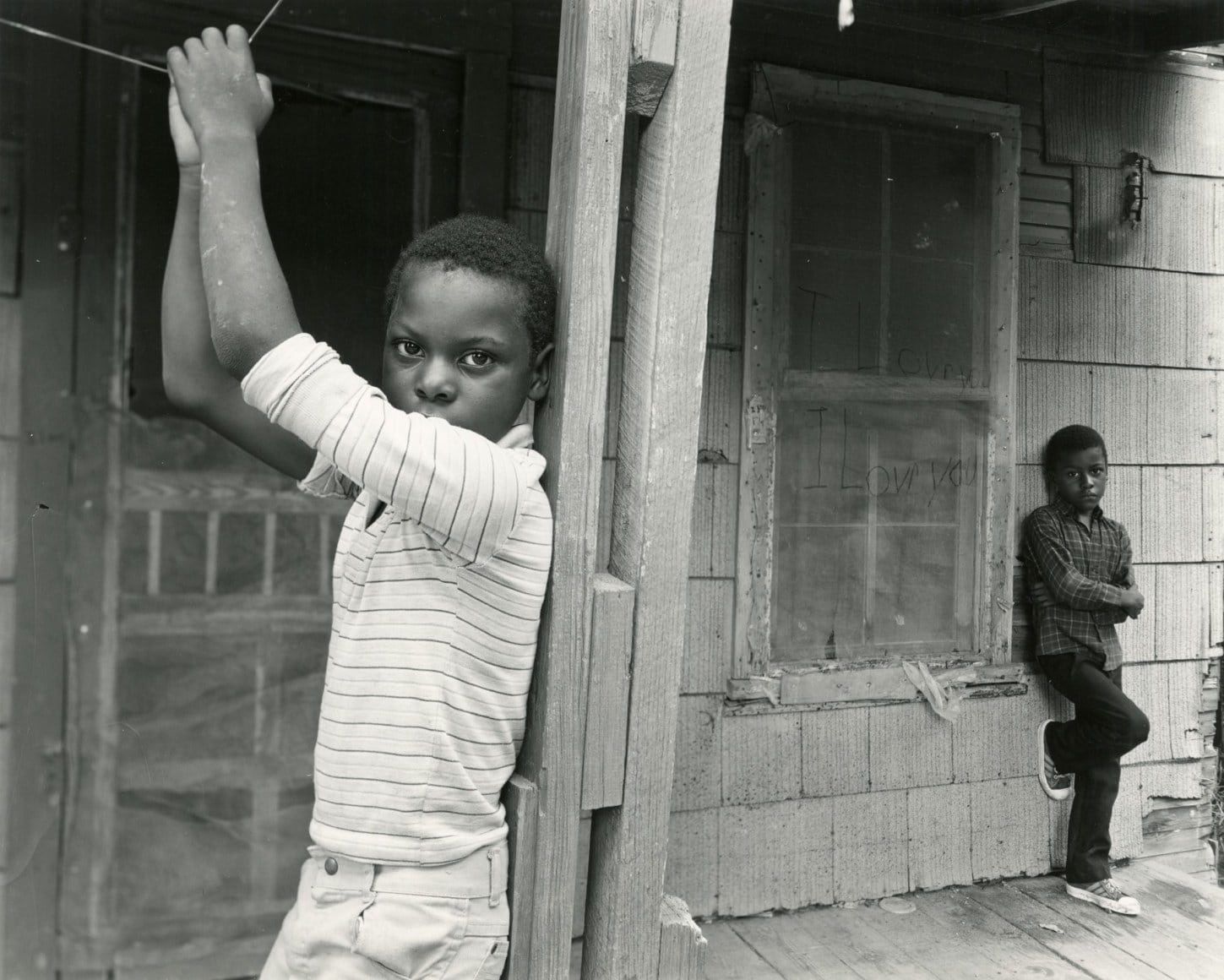

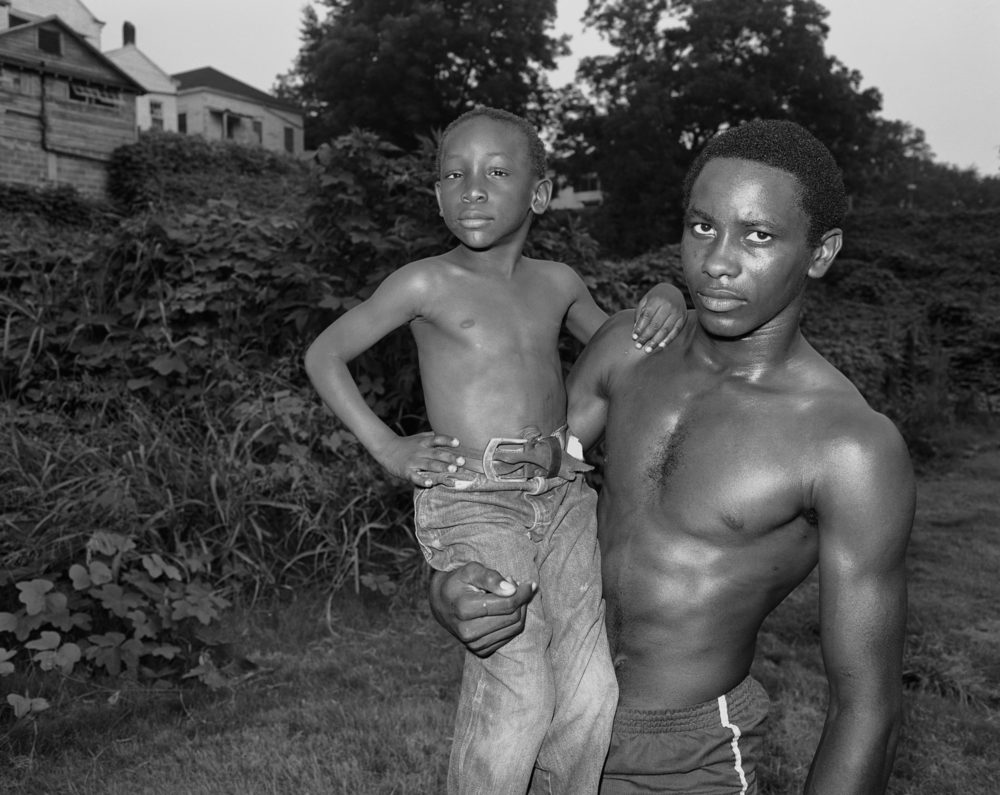

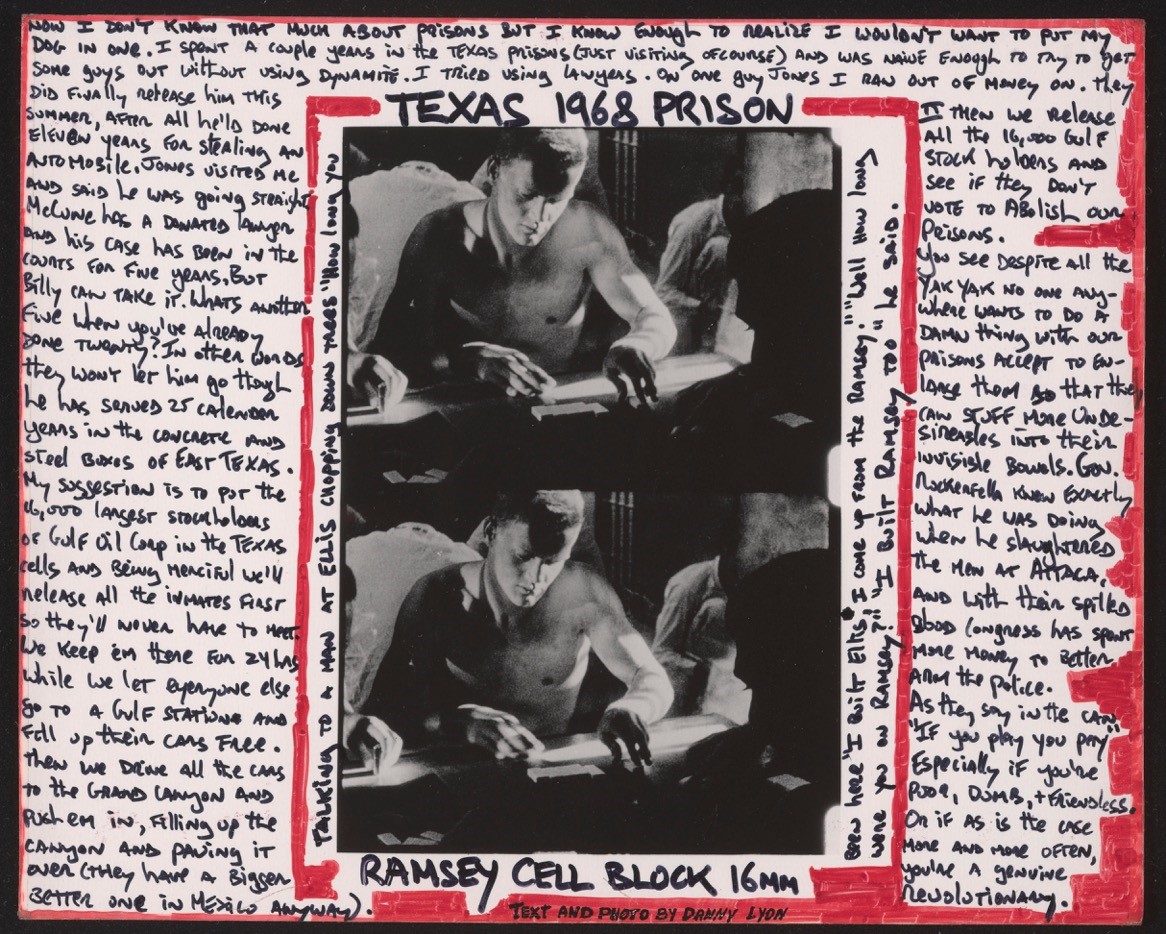

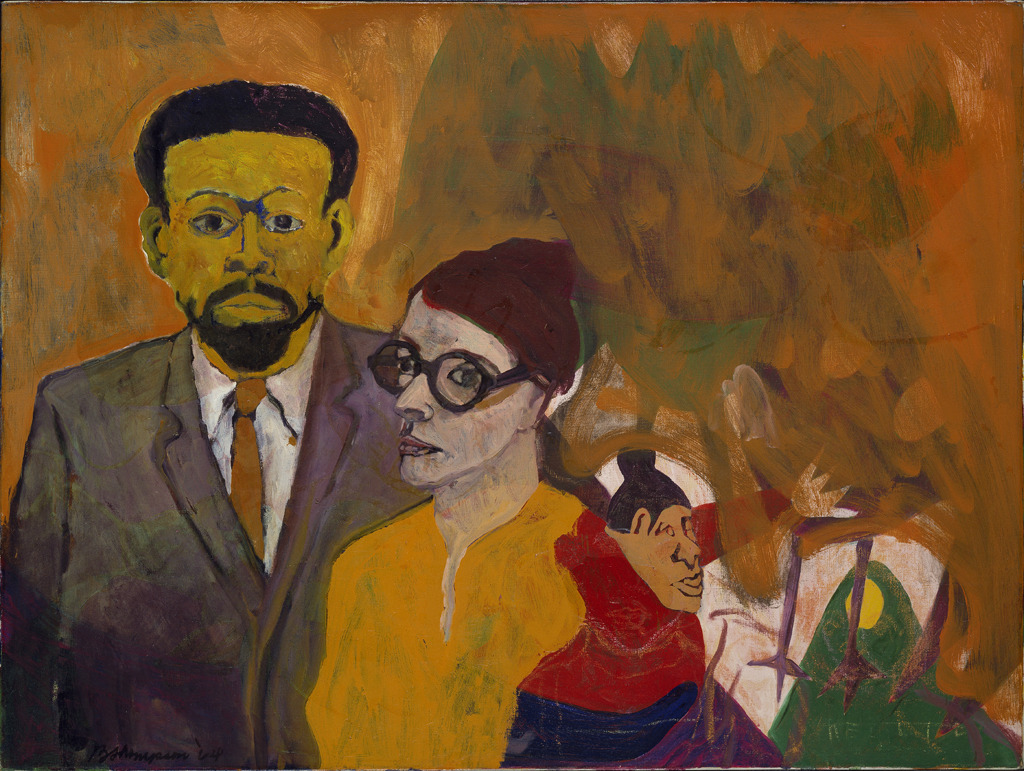

Jo began making true-to-life art in the 70s. Jo and Jeff—her collaborator on most of their films—broke the rules of any institution or grandee[1] that would rein them in but they had a few verbotens of their own—”never interview, never ask anyone to do (or repeat) anything, never ask people what their plans are, never turn on the lights, never show up without your cameras.”[2] Their method was simple yet radical—”hang out and shoot and be yourself.” Jo and Jeff’s refusal of artifice meant these mavericks weren’t made for this art-world. But a report on museum screenings of Jo’s Demon Lover Diary (1980) confirms their films came through anywhere…

The Whitney audience was delighted. While there was a small “in” crowd of film students—you could hear people arguing about lens and f stops—most were ladies in fur hats, college students and other Sunday afternoon museum denizens. “And best of all,” I heard one older woman say, “it was real.”[3]

Jo was born with an instinct for the actual. She drove our mom mad because her dolly looked irreal when laid in her toy-pram. (Baby’s limbs didn’t hang right.) Jo was always precocious, always beautifully girlish.

School tended to be a drag—though Latin swung—and she got out quick since she skipped Junior High School. By age sixteen, she was off to Radcliffe for (what she termed) “an unspectacular academic career.” Though Cambridge in the 60s was a good trip. And she liked directing plays and writing film and theater reviews for the Crimson. You can read a few of her best bits in this review of Kael-inflected pop criticism. Lines from Jo’s review of an art-house sensation by a now forgotten Scandinavian auteur (one Vilgot Sioman) are still a hoot so at the risk of harping on juvenilia…

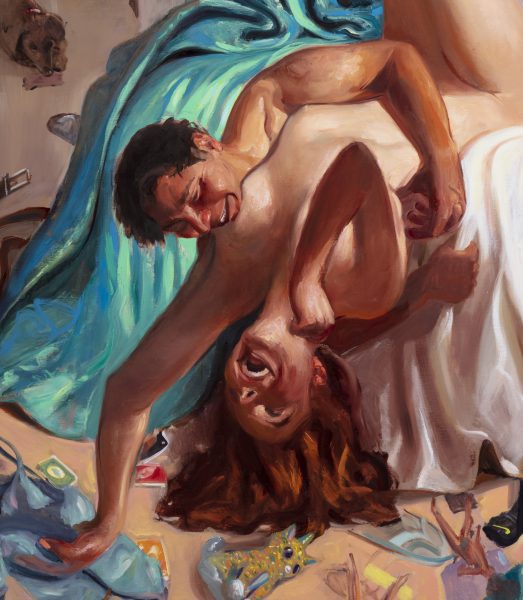

My Sister, My Love is a not entirely sunny picture of life in medieval Sweden…

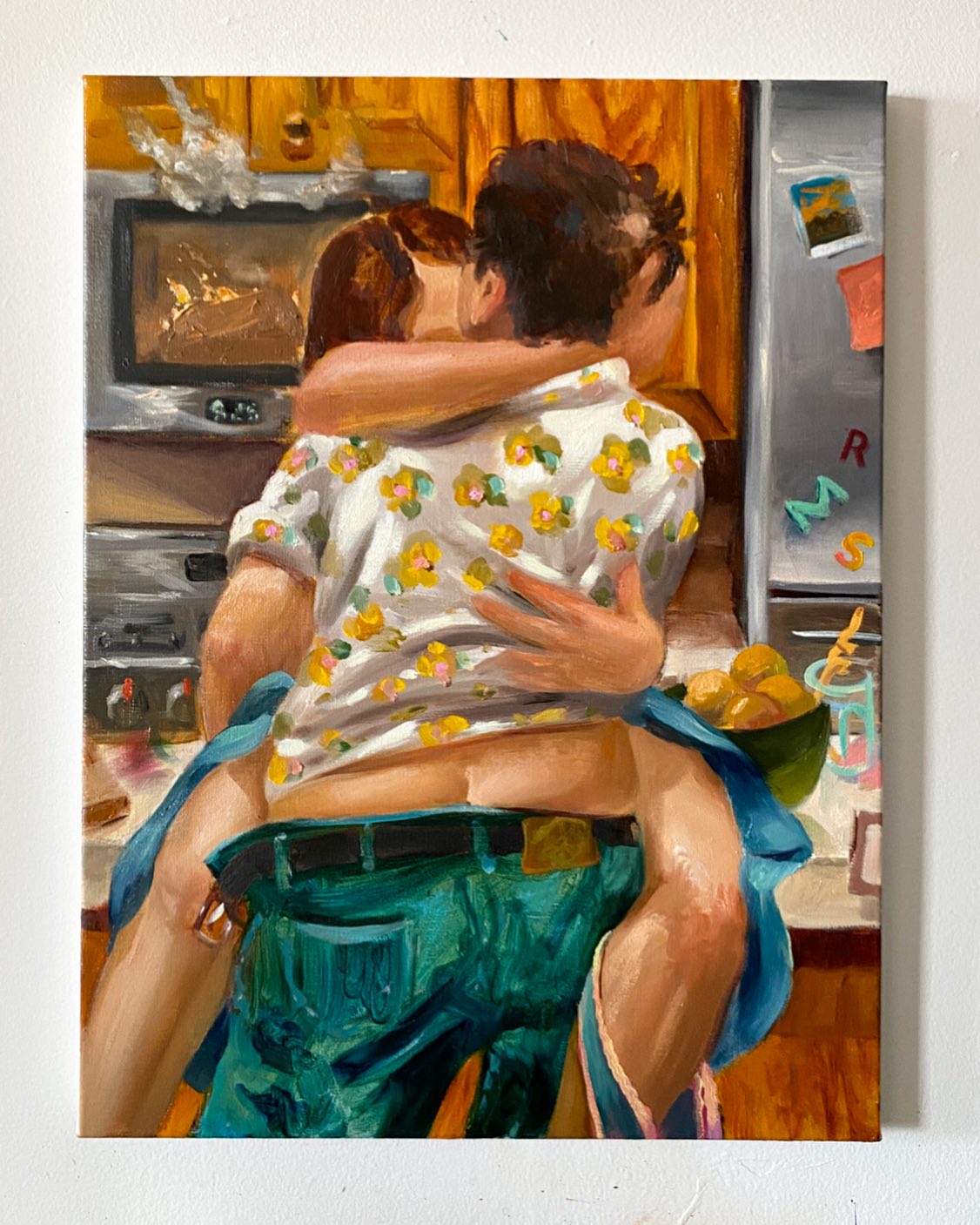

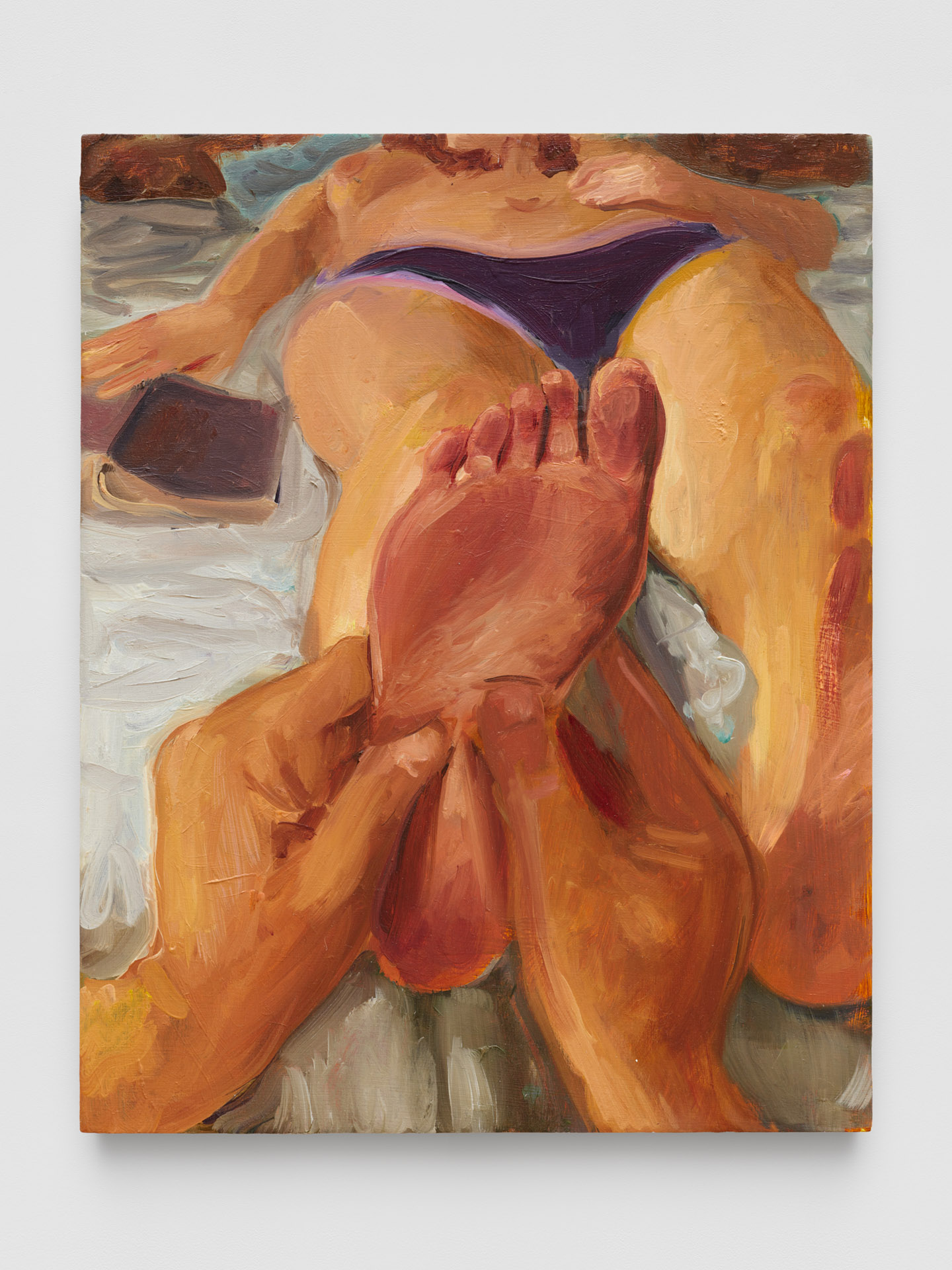

Sioman cheats even in the love scenes that Playboy found so frank and the Boston police so objectionable. The scenes have superficial honesty because the bodies are naked. But that’s it…

The last straw is the cast. Bibi Anderson (the sister) and Per Oscarsson (the brother) tease you for 50-odd minutes. She’s so beautiful, he’s so wolfish, you expect that the wages of sin will be excitement. But Sjoman doesn’t keep them on screen long enough to produce a stir. At the end he removes them completely in favor of a screaming baby. Leave early.

Jo was never at the mercy of any crowd or bamboozled by the next big art-con. Thirty years on—after the lights came up at a family watch-party—her nose for the real nailed Tarantino’s Reservoir Dogs: “Stagey piece of shit.”