‘The artistic imagination continues to dream of historical agency.’ — Martha Rosler [1]

‘Activist art functions as a glitch within art history that threatens to invert the “figure and ground” of the narrative.’ — Kim Charnley [2]

In the Spring of 2012, artist and director Zoe Beloff staged Bertolt Brecht’s play “The Days of the Commune,” at Zuccotti Park with Occupy Wall Street with some performers recruited from OWS participants. Photo by Julia Sherman.

Like a ‘one-man wrecking crew,’ is how critic Michael Fried described Gustave Courbet.[3] The 19th century painter labeled his own practice ‘realism.’ Bereft of sentimentality or idealized representation, Courbet’s 1849 canvas The Stonebreakers, depicts two men engaged in punishing, monotonous labor. Under a hot but setting sun, the figures toil unabated. Grant Kester writes that Courbet’s painting represented ‘the laboring body as a calculated affront,’ while Linda Nochlin points out that Courbet’s canvases were ‘socially inflammatory not so much because of what they said – they contain no overt message at all – but because of what they did not say.’[4] In either case, the painter did not patronize his impoverished subjects, instead he produced works so “startlingly direct” that the 1855 Paris Salon refused to include his canvases for its esteemed annual exhibition, the artist staged his own private exhibition enacting a sort of Salon des Refusés avant la lettre. Courbet and his circle of realist artists and intellectuals are frequently cited as the most important reference point for both the legacy of the artistic avant-garde, as well as socially engaged art and art activism, that is to say, on those few occasions when the latter is treated as a chronological phenomenon. As esteemed social art historian T.J. Clark put it, ‘if any artist came close to creating the conditions for revolutionary art, it was Courbet.’[5] He goes so far as to challenge future art activists stating that, ‘after Courbet, is there any more “revolutionary” art?’[6]

Even so, I confess now to having misgivings about positing Courbet and his legacy as a starting point for explaining how, and why artists become activists. One obvious concern is that his name is about as proper an art historical signifier for the white male genius that one can conjure-up. If progressive art scholar Clark dreamt of that singular starting (and perhaps ending point) of art’s political narrative, who am I to push back? How would one challenge this procreative narrative? And yet, in our era of decolonization movements and Black Lives Matter, simply returning to the familiar Eurocentric patterns and methods of scholarship seems neither appropriate nor credible. How to chronicle the rising and falling of art activism differently, while providing contemporary practitioners, students of art and cultural theorists, with some sort of critical genealogy that complicates the standard demand for founding fathers and original maiden moments of inaugural commencement? Which is why Fried’s acerbic comment about Courbet’s loathing of tradition opens-up a useful paradox. I like to think if Courbet were here now, among us, that he would agree. The painter of everyday material life would recognize that any attempt to narrate a history for art activism requires both impudence towards conventions, and a tolerance of winding travels through labyrinthine spaces.

The Commune

As a friend and follower of anarcho-socialist philosopher Pierre-Joseph Proudhon, Courbet was indeed a frequent anti-authoritarian transgressor. The painter delivers his most pulverizing performance on 12 April 1871, by assisting the Parisian Communards in toppling the Vendôme Column, Napoleon’s protuberant monument to France’s imperial conquests. And yet, Courbet was at best only an occasional wrecker. As Nochlin observes, his paintings were not ostensibly political, not even during the sensationally revolutionary year of 1848 when Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels publish The Communist Manifesto. ‘To each his own: I am a painter and I make paintings,’ he writes dreamily to his family while all around him Paris, and much of Europe, become a battleground.[7] More significantly, and this is the first aspect of our conundrum, the realist painter was just one of several thousand men and women who took part in The Commune, even though Courbet is later among those singled-out by the restored French government and penalized for his participation in the uprising, specifically for felling the column.

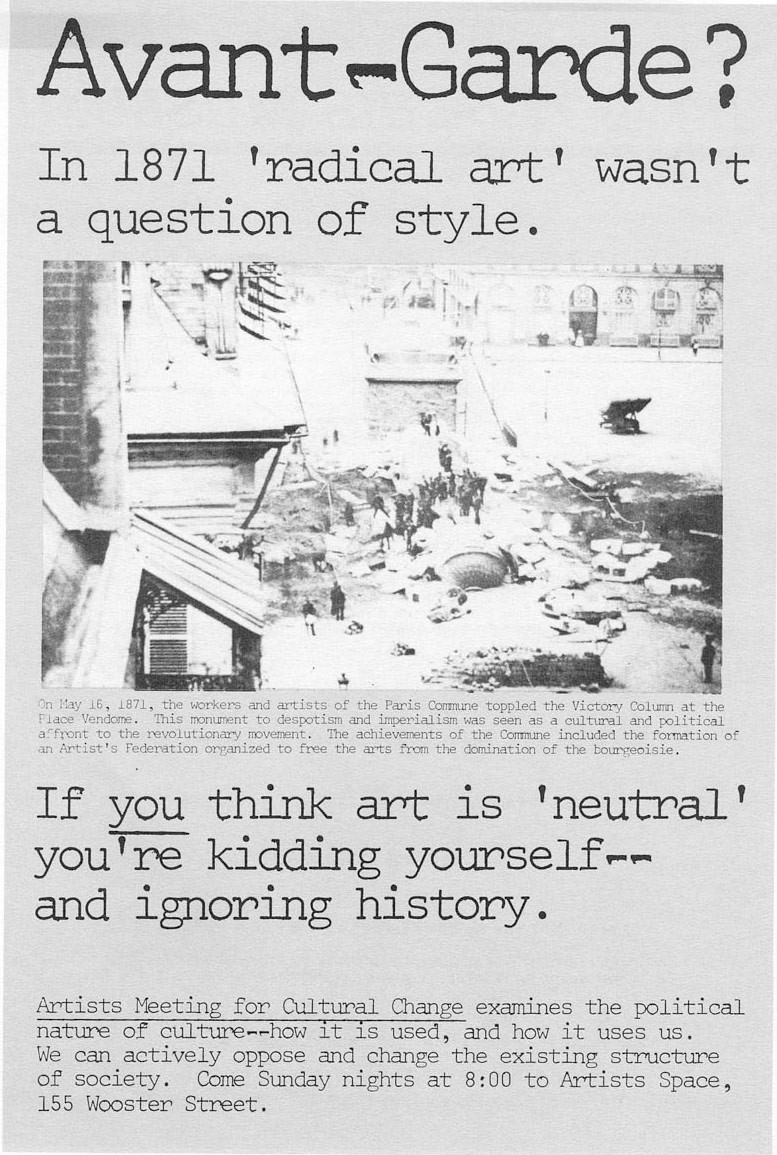

Some 20,000 less fortunate Communards were executed on sight during the ‘The Bloody Week’ (La semaine sanglante) from the 21st of May to the 28th, their corpses photographed in slapdash coffins, before being buried and forgotten.[8] After re-taking Paris from the revolutionaries, the French government hurriedly installed a duplicate memorial to Napoleon, charging Courbet for its replacement cost. The artist died in exile without delivering a single payment. Meanwhile, photographic images of the fallen monument – some of the first ever taken of armed conflict – were distributed as souvenirs using the new printing technology of cartes postales. (In the mid-1970s, one of these photographic momentos is repurposed by the art-activist agenda of Artists Meeting for Cultural Change, to illustrate another attempt to directly link art with social activism.)

Although Courbet is a favored entry-point into the history of art and politics, as well as art activism, the customary anchor for periodizing such practices is the mid-to late 1800s itself, and especially the aforementioned 1871 Commune, an event that feminist scholar Silvia Federici describes as akin to a medieval witch-hunt with regard to the brutal apprehension and slaughter of Communard women, while theorist Terry Eagleton sees it today as ‘a kind of Marxian sublime.’[9] In March 2021, a Parisian street banner proclaimed ‘We don’t care about May ’68, we want 1871.’[10] Perhaps this is because, in contrast to the Great Refusal of the 1968 revolution, with its idealization of liberation through aesthetic creativity, the Paris Commune and its Federation of Artists (Courbet serving as elected Commissioner of Art), sought by contrast to abolish the stodgy École des Beaux-arts, demanded competitive exams for all art instructors, did away with artistic medals and other honours, launched a cultural newspaper, and called on artists to ‘assume control of the museums and art collections, though the property of the nation, are primarily theirs, from the intellectual as well as material point of view.’[11] Practical reforms that we will encounter ninety-eight years later with the Art Workers’ Coalition who similarly demanded control over New York’s cultural institutions, though always keeping artists, as a privileged, yet integrated social sector, operating within certain useful boundaries.

This echoing effect retroactively transforms the Paris Commune into a virtual primal scene for activist art and art activism, with such later projects as Tucumán Arde in 1968 Argentina and the Situationist International in Paris that same year, along with Occupy Wall Street 2011, and the monument take-down movements, or monumentacides of 2020, all serving as successive symptomatic repetitions of this inaugural trauma.[12] Switching from psychoanalytic to theological tropes, Courbet serves as the favored progenitor of political and activist art as a classic conversion story. The introspective ‘maker of paintings,’ is reborn as an agent of revolutionary change in a quintessential moment of awakening. Art merging with life becomes more than simply ‘art,’ metamorphosing before our eyes into direct social activism and explicit political protest.

Here I can’t help recalling questions raised by Egyptian artist Doa Aly during the 2011 Tahir Square occupation in Cairo. ‘Is there a time for art?’ she prods as teargas and rubber bullets fill the city streets, before answering herself in words that chastise the inaction of some fellow artists.

The place for reactionary art in history is secured by history itself. After a devastating bombing or a political victory, there’s no time for art. That is to say no time for contemplative reflection, for philosophy. It is time for action; solidarity or celebration, and anything else seems inappropriate…what is happening ‘now’ is bigger than art’s limited ability to grasp and address it. Why then try to squeeze the elephant back into the cupboard?[13]

I hardly need to point out that Communard Courbet might have penned these same sentiments one hundred and forty years before the Egyptian Revolution, just as similar insights are found amongst contemporary Black Lives Matter cultural activists today. No doubt, what has exited the cupboard – or fled Adorno’s offices – appears impossible to put back. This too has roots in the very category ‘art.’ According to cultural sociologist Pierre Bourdieu, it was in quattrocento Florence when artists gained the right to legislate their production ‘within their own sphere,’ though not without complications then and thereafter.

Ironically, armed with this socio-economic autonomy, art has, especially since the 19th century, frequently sought to return to a state of broader social significance, including calling for the abandonment of its own hard-won autonomy. As theorist Stephen Wright more recently asserts, art is now attempting to escape from itself, and its own ontological conditions of a-historical isolation. We can see this “escapalogical” attempt at a prison break as far back as the Russian avant-garde, and with Marcel Duchamp’s insistence that utilitarian objects – an industrially produced snow shovel and ceramic urinal – were, if he selected and privileged them as such, works of art. But today, the degree of this breaching appears quantitatively different. While agreeing with Peter Bürger’s famous critique that post-war artists normalized the early avant-garde’s radical rejection of autonomy, Wright’s proposition, contrarily, claims to see a complete disappearing act in the works. Art vanishes without a trace, leaving behind no clues as to its point of departure, not even a Cheshire grin. Unless, perhaps, we detect this escapee reemerging as an aesthetics of activism in streets, squares, inside museum lobbies and within online networks?

Page 78 from An Anti-Catalog, 1977, a collectively produced publication by The Catalog Committee of Artists Meeting for Cultural Change (AMCC) that sought to call ‘into question the neutrality of art scholarship and its cultural institutions.’ Image courtesy of the author’s archives.

Methods & Omissions

In order to move forward we need to revisit the problems of a methodology about art activism, including its analysis, theory, aesthetics and chronology. I mean, why not just write an art history of activist art and art activism placing Courbet as a starting point? One answer already cited involves the necessity of reimagining our cultural narratives with a broader array of participants that includes working-class populations, women and children, as well as Indigenous people, the colonized, non-White peoples, and queer and disabled communities. But it also means acknowledging the damage done by not embracing these diverse cultural producers and their often-overlooked contributions, including their refusal to participate in a ‘history’ of art as written by the victorious and privileged classes. This harm takes several forms, including reinforcing a culturally narrow outlook that has facilitated the policing of a dominant Anglo White Male Eurocentric interpretive paradigm, while actively excluding or diminishing marginal voices, or at least marking the heft of their absence, as if dancing about the rim of an absent episteme. Though, as I write this, such systemic inattention is finally being addressed, as a new generation of artists, art historians, cultural theorists and critics recognize how very much the field of artistic scholarship is hobbled by such neglect.

Yet another problem to overcome is acknowledging that art historical scholarship pivots on recognizing a few outstanding and talented individuals whose singular, authorial vision produces a lineage of significant artifacts and images. Contrarily, all modes of political dissent, cultural or otherwise, emerge from conflicts which are, by definition, larger than the immediate concern, the vision, or the actions of any single person. Call this the Courbet conundrum, or the Cairo challenge, or whatever you prefer, but these practices are always inherently social and non-individualistic, oftentimes self-consciously communal, collaborative and at times collective. By contrast, standard interpretive methods of artistic research inevitably wish to assign a singular point of origin, as well as typically a founding figure for such phenomenon. Tackling this impediment means recognizing the paradoxes of a spectral sociality for and against artistic activist agency. In 1871 Paris, for example, a mostly nameless collective mass included artists, laundresses, milkmaids, bakers, small shop owners, national guardsmen, laborers and children, all suddenly radicalized by historical circumstances: a multitude of ordinary people, constituting what theorist Michel De Certeau labeled the murmur of societies.[15]

One immediate target of the Communard’s justice was the Vendôme Column that revolutionary Louis Barron later described as a ‘fragile, empty, miserable’ symbol of Napoleon’s chauvinistic atrocities. However, Barron also recalls fellow radicals dancing ‘in a circle around the debris’ before leaving ‘very content with the little party.’[16] At this primal level of liberatory jouissance, the column’s destruction recalls and reenacts such aesthetic forms as festive street carnivals or fêtes, organized almost a century earlier by artist Jacques-Louis David in support of the 1789 revolution, communal events that reenacted such the burning of the Bastille among other past insurrectionary moments. But meanwhile, this void producing practice and intentional historical repetition also leaps forward in anticipation of contemporary forms of activist art yet to come.

Pivoting-off post-2008 fiscal crisis unrest in 2012 New York City, artist Zoe Beloff tunneled backwards from the present to re-stage Bertolt Brecht’s 1955 play ‘The Days of the Commune,’ as part of the Occupy Wall Street encampment at Zuccotti Park. Beloff and her team of collaborators resurrected that ‘murmur’ of communal resistance, thanks to the way revolutionary moments generate gaps and displacements in time and space, to cite theorist Kristin Ross.[17] She illustrates her thesis with the Communard’s demolition of Napoleon’s Vendôme column, insisting this was less as an act of vexed destruction, than a re-appropriation by the multitude. Ross states that it was a joyful rejection of ‘the dominant organization of social space and the supposed neutrality of monuments.’[18] As with Occupy, or Black Lives Matter, and the actions of the global monumenticide movement in recent years, such interventions produce what Ross calls a ‘positive social void.’[19] This is not, however, a cavity to simply fill back-in with new content, no matter how socially progressive. Much like the archive of activist art and the art of activism, this positive social void is a not-thing, or a nothing, constituting of a radically sublime agency from an inherently absent collectivity.

Questions

Several questions linger. We have already encountered the first of these, the dilemma that rises when trying to recognize individual activist art practitioners as opposed to collective modes of cultural production. But we also need to ask if this cooperative cultural collectivism – in its simultaneously concrete and abstract social presence – can be rendered through any representational means. Is social agency ever really portrayable? There is more to say about this, but an equally fundamental question is this: just what sort of historical periodization can be applied to a phenomenon that has no obvious formal program, lacks a singular manifesto, gives rise to no school or canon, and is not systematically collected by museums (though a few archives do have substantial holdings about activist art[20].

Perhaps most frustratingly, this historical dossier punctuates, rather than connects, activist art and events across chronological time, absent precise pattern or prediction. In other words, can something that operates as a repetitive, subsurface and excessive or surplus archive produce any meaningful narrativization? Obviously, if not, then a key aim of any analysis of activist art and its past practices is already lost, but such an outcome also denies the possible heuristic value of this overabundant archive, one which is constantly and actively repurposed, repaired, restaged, and even mis-interpreted all the way back from the time of the Haitian Revolution, Paris Commune, the Russian Revolution, on up to the Argentinian avant-garde of the late 1960s, and of course the SI, and the agitational Atelier Popular screen-printing workshops set-up during the student and worker revolution of May 1968 Paris. Add to this legacy more recent forms of cultural dissent arising under the Cold War, neoliberalism, the Internet and during our recent moment of COVID lockdown, including interventionist groups such as Decolonize This Place, and Black Lives Matter. By focusing on the lacuna, deletions and glitches, citing Charnley, of the surplus archive, while acknowledging the persistence of hope, as expressed by Rosler, what begins to materialize is a counter-epistemology that stems from both known and unknown sources, European and non-European cultural influencers, and the overall collective resistance to class exploitation, misogyny, militarism, white supremacy, colonialism and other socio-political injustices. It is out of this and other dense inventories of imagination, possibility, failure and repetition that the vibrant agency of activist art and the art of activism is incessantly drawn and redrawn, then drawn again.

* This essay is a prelude to a forthcoming book on the repurposing and repetitions of activist art’s surplus archive.

Notes

1 Martha Rosler, “The artistic mode of revolution: from gentrification to occupation.” Joy Forever: The Political Economy of Social Creativity.” MAYFLY Books, 2014. p 194.

2 Kim Charnley, “Art on the Brink: Dark Matter and Capitalist Crisis.” Unpublished draft essay, June 29, 2016.

3 Michael Fried, ‘Painter into Painting: On Courbet’s “After Dinner at Ornans” and “Stonebreakers,”’ Critical Inquiry 8, no. 4, 1982, p 619.

4 Grant H Kester, The One and the Many: Contemporary Collaborative Art in a Global Context, Duke University Press, 2011, p 100; Linda Nochlin, Realism, CUP Archive, 1971, p 46.

5 Timothy J. Clark, The Absolute Bourgeois: Artists and Politics in France, 1848-1851, Univ of California Press, (1973) 1999, p 180.

6 Timothy J. Clark, Image of the People: Gustave Courbet and the 1848 Revolution, Univ of California Press, (1973) 1999, p 154. Clark’s sobering comment has its own historical context. It was written in the aftermath of the failed student and worker uprisings of 1968 in Paris and elsewhere, and first published a year after the Parisian based Situationist International (SI) collapsed, a group that once called upon ordinary people to take their desires for reality, and with whom Clark was briefly associated.

7 From a letter dated March 1848, cited in Courbet, Gustave, and Petra ten-Doesschate Chu, Letters of Gustave Courbet, Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1992, p 77.

8 Numbers vary, but some around 20,000 men, women and children were killed in the ‘Bloody Week’ starting the 21st of May 1871, others were forced to become French colonizers by being deported to New Caledonia in the South Pacific.

9 “Yet the specter of the witches continued to haunt the imagination of the ruling class. In 1871, the Parisian bourgeoisie instinctively returned to it to demonize the female Communards, accusing them of wanting to set Paris aflame,” Sylvia Federici, Caliban and the Witch, Autonomedia, 2004, p 206. And “The nature and characteristics of the Commune, its content – collectivism, mass participation, transformation, tensions, contradictions and self-criticism – represent a kind of Marxian sublime,” Terry Eagleton, The Ideology Of the Aesthetic, Blackwell, Oxford, 1997, p 214.

10 Julian Coman, “Vive la commune? The working-class insurrection that shook the world,” The Guardian, 7 March, 2021.

11 Gonzalo J. Sanchez, Organising Independence: The Artists Federation of the Paris Commune and Its Legacy, 1871-1889, University of Nebraska Press, 1997, p 43-44.

12 For example, following Lucy R. Lippard’s brief mention of Tucumán Arde in her 1973 book Six Years: The Dematerialization of Art, the Argentinian project is again discussed in Alberro and Stimson (1999), Charles Esche and Will Bradley (2007), Luis Camnitzer (2007), Kester (2011), Julia Bryan-Wilson (2011), Claire Bishop (2012), and continues to be cited by scholars seeking to chronical politicized and socially engaged art, myself included.

13 Doa Aly , ‘No Time for Art,?’ accessed at Another blog about last night : https://moabdallah.wordpress.com/2011/06/15/no-time-for-art/

14 Pierre Bourdieu, The Field of Cultural Production: Essays on Art and Literature, Columbia University Press, 1993, p 113.

15 Michel De Certeau, The Practice of Everyday Life, University of California Press, 1984, p v.

16 Ibid.

17 Kristin Ross, ‘Rimbaud and the Transformation of Social Space,’ Yale French Studies, no. 73, 1987, pp 104-120.

18 Ross, ‘Rimbaud and the Transformation of Social Space,’ p 113.

19 Ibid.

20 Examples include Interference Archive in Brooklyn: https://interferencearchive.org/, NYC; Center for the Study of Political Graphics: https://www.politicalgraphics.org/ in LA; the Political Art Documentation/Distribution Archive (PAD/D Archive) at the Museum of Modern Art in NYC: https://hyperallergic.com/117621/art-in-the-1980s-the-forgotten-history-of-padd/, and such online collections as https://www.postwarcultureatbeinecke.org/workinggroup; http://www.darkmatterarchives.net/ ; Heresies Archive http://heresiesfilmproject.org/archive/ ; ABC No Rio: https://98bowery.com/return-to-the-bowery/abcnorio-the-book

Gregory Sholette blogs at: https://gregsholette.tumblr.com/ His website: http://gregorysholette.org Archives: http://darkmatterarchives.net