Green Street in 1969

Green Street in 1969

The first loft I lived in was on the north side of Broome Street, between Crosby and Lafayette. I sublet it for the summer of 1969 from an artist by the name of Jack Whitten.

A Website of the Radical Imagination

Green Street in 1969

Green Street in 1969

The first loft I lived in was on the north side of Broome Street, between Crosby and Lafayette. I sublet it for the summer of 1969 from an artist by the name of Jack Whitten.

My first brush with the audience for Film Forum’s Ozu retrospective was a trip. I got off on the wrong block and ran into another Ozu-er who was lost too. As we found our way around the block to the theatre, he told me he saw Tokyo Story when he was teenager, which led him (eventually) to spend decades in Japan where he got married. His Japanese wife met us at the theater.

I so vividly remember watching the Jackie Gleason show with my family as a kid. I always loved the finale when Gleason would do the Joe The Bartender sketch and Frank Fontaine’s Crazy Guggenheim would come out. (Seemed like all the boys in my grade school class watched Gleason because we’d all take a shot at impersonating his signature laugh thereby driving our supervising teachers — what else? — crazy.) The inebriated Guggenheim would tell some wacko story, get a lot of laughs and then, at Gleason’s request, sing an old-timey ballad in the most beautiful baritone around.

I am standing on West Ninth Street in Bensonhurst, Brooklyn, sometime in the 1930s: a horse-drawn ice wagon has just come down the street, and I am looking at the golden apples the horse has dropped and saying to myself (not the horse), “Your necktie is maroon.”

My mother had an elegant way with colors, which devolved on us children, a flair she developed along with her flair for elegant names; this was clear in the voluntary refinement of her name from “Esther” to “Estelle”—a habit acquired by her younger brother Yitzchak (Isidore, Izzy), who chose to be known to the world as “Morton.” My father, an affable salesman of millinery (i.e., ladies’ hats), did not care for his eccentric brother-in-law; and when he called, my father would answer the phone, saying almost nothing but declaring to my mother, after she had asked who’d called, “Itza Mutt,” reducing her to literally helpless laughter. My father liked to make my mother laugh so hard that she had to run, as best she could, out of the kitchen . . . but I digress.

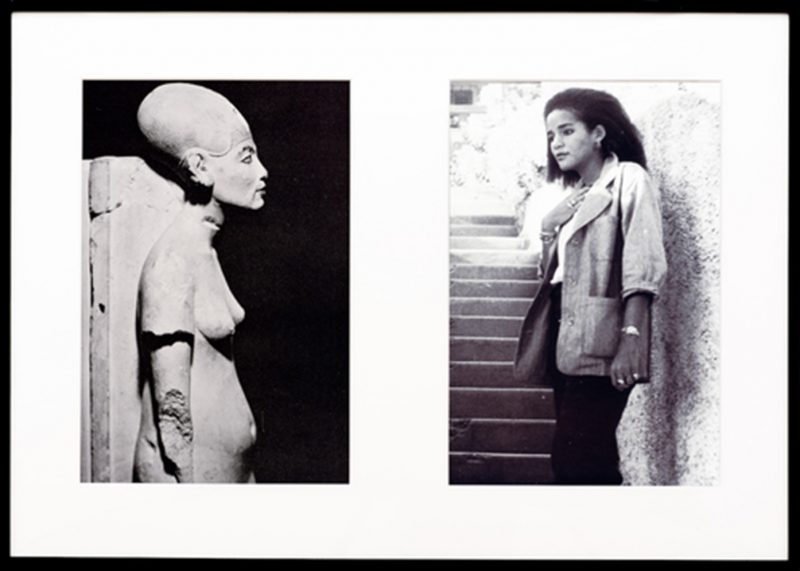

Manhattan’s Just Above Midtown (JAM) gallery became a haven for Black Atlantic artists in the 70s and 80s. A current exhibit at MOMA chronicles work first shown at JAM and includes art by Lorraine O’Grady. The author of the following post was born long after JAM’s moment. He encountered O’Grady’s work on the campus of the University of Chicago. It launched him on a trip that took him back to the playful start of his own art-life…

I came across one of the sixteen diptychs that make up Lorraine O’Grady’s Miscegenated Family Album—(Cross Generational) L: Nefertiti, the last image; R: Devonia\’s youngest Daughter, Kimberley—in the the Booth collection.

“New York: 1962-1964 explores a pivotal three-year period in the history of art and culture in New York City, examining how artists living and working in New York responded to their rapidly changing world, through more than 180 works of art—all made or seen in New York between 1962-1964.”

Pallie Greene – the kid from our hood who dunked at our block party (above) – began playing ball late just like my late brother Tom, who didn’t get into the game until Jr. High school. Might be a life-changer for Pallie though. It sure made a difference to Tom. When I think about how he came to make his life on Tiemann Place (as he worked at the 125th St. Post Office), aesthetics and politics of b-ball – along with people’s soul musics – are keys to his story. Tom was out there with Pallie – a spirit, not a ghost! – as our hood re-upped on the tradition he invented (with the West Harlem Coalition). The 34th Annual Anti-Gentrification Street Fair jumped off on a proud Saturday in September.

My mother’s maiden name was Claudette Winfield. Her twin brother was named Claude Winfield. She left home for college to attend Jackson State University and met a young man named Claude McInnis who was named after his uncle Claude Brown. That’s a whole lotta damn Claudes, which is why my Pops never intended for me to be a junior. My mother’s twin was her best friend until the day she died. As siblings, they argued and disagreed often. As siblings, no one else could say anything bad about the other one. So, when I learned Wednesday that my mother’s twin, my Uncle Claude, had passed, I realized that is the end of the Claudes. But, more importantly, that is the end of one of the most important people in my life.

William Kornblum’s Marseille: Port to Port is (per Howard Becker) “a new kind of travel book.” What follows are (slightly adapted) excerpts from Kornblum’s testament to sociological imagination and soulful uses of ethnographic method…

My late brother Tom’s second mother (in law) died on Monday in D.R. Teresa Prestinary, of Monte Cristi and New York City, made 105. She had five children of her own but she raised plenty more on both islands. Per her grandson Jamie who told me that on vacays in D.R. he ran into hombre after hombre who thought of her as his own matriarch. I lived up the block from Mama Pres (when she was in New York rather than D.R.) and was often underfoot in her apartment or at my brother’s and sister (in law) Maria’s place across the street. In all that time I never heard Mama Pres say a cross word to anyone ever. The last of 20 children she seems to have been treated as a late gift from God by her family in D.R. So she grew up to grace everyone she met. She had a special connection with my wife (who is the first of 20 children). I can see them now shucking corn on my parents’ porch in the Berkshires, taking the breeze, and laughing together. Maybe they were talking about the odd DeMott fam they’d somehow got mixed up with. Or maybe they were recalling rites they’d performed to ward off witchcraft by Santerian drug-dealers who’d made my wife’s life hell when she opened a $10 clothing store on 140th and Bway back in the ’00s. (The two of them had tested my two year old son’s pee to see if it had prophylactic powers after my wife found chicken blood spattered on her store’s door.)

There have been more poems in recent First batches, thanks chiefly to Alison Stone whose work and way in the world has brought other poets to us. That efflorescence, in turn, has made me think I should try harder to bring attention to the poetry of my late friend Robert Douglas Cushman. What follows are poems from his book, “The City Among Us.”

Long ago and far away in San Francisco, that lovely city by the bay, I maneuvered myself into the food concession at the Keystone Korner, a jazz club in North Beach. It was 1975, and I had many strange and wondrous adventures there.

“Westside Story 2021.” A yes for me. We watched it through, surprised and moved by crazy young love brought vividly to life in this cast’s Tony and Maria. I kept thinking, no, they have a chance, they’ll get out of the Shakespeare play they were born in, like the street where you were raised and the language that formed you. Valentina will give them bus fare and Anita will not betray them after she is almost gang raped. Justin Peck’s balletic remastering of the Robbins dances. The screenplay by Tony Kushner. The Spanish spoken throughout without subtitles. Spielberg’s camera adds wings to the play, turning it into a movie that’s a play set in the way we see things now. Every story is about the time it’s told in, not the period depicted, and this one is about something’s coming. Gustavo Dudamel conducts the rapturous, jazzy Bernstein score that doesn’t get old. And never will.

This Q&A with Robert Farris Thompson was originally posted at the Sotheby’s website in 2020, when the auction house was charged with selling paintings given to Thompson by Jean-Michel Basquiat and Keith Haring.

Immigrants, artists, tycoons seek New York.

Bloodstains from aborted dreams streak New York.

To friends from elsewhere, even the name awes.

Their eyes widen when I speak of New York.

Fickle city, we moth-fly toward your light.

You bless the rich, feed on the weak. New York

Toni Cade Bambara’s “Working At It in Five Parts” is a hidden gem of prismatic self-reflection that we were surprised to find collecting dust in the Spelman College Archives along her voluminous letters, story drafts, teaching lesson plans, and much more.

Thanks to Columbia U’s expansion, a chump can now get a chi chi egg/sausage McMuffin for $10 in my hood. That bad deal goes down at Butterfunk Biscuit Co—one of four mini-restaurants in the deeply unfunky “Manhattanville Food Market” located on the first floor of a building in CU’s sterile new STEM complex just above 125th St. Don’t this…

make you want to go home to a Pre-Columbian West Harlem?

First’s original editors, longtime New Yorkers, were fully alive to experiences of love and death on 9/11. We printed a set of responses to the attacks that implicitly contradicted those who assumed “anti-Americanism is a necessity” (without imposing a patriotic litmus test). Our post-9/11 issue featured red, white and blue colors above the fold, though that wasn’t a simple flag-waving gesture. The exemplary citizens (and New Yorkers) invoked on our cover were Latin Americans and an Afro-American: La Lupe, Eddie Palmieri and Jay-Z.

I’m reminded of how our colors seemed out of time to the all-knowing Left when I listen to commentary by pundits like Mehdi Hasan who link the post-9/11 “War on Terror” with l/6. That tendentious timeline all but erases the threat once posed by radical Islamists. It assumes American Islamophobia/xenophobia was always a scarier thing than Islamofascism. (I wonder if Mehdi Hasan noticed what happened to Samuel Paty—the French middle school teacher who was decapitated last October after he dared to teach his students about the Charlie Hebdo murders.) While it’s probably true the threat to Americans and Europeans from Islamist terrorists has diminished in recent years, that’s due largely to those Kurdish fighters who turned the tide against ISIS at the battle of Kobani. Future historians may come to see the Kurds’ victory there in January 2015 as the true culmination of the war that blew up in America on 9/11. The Kurds certainly grasped the meaning of their victory: “The battle for Kobani was not only a fight between the YPG and Daesh [ISIS], it was a battle between humanity and barbarity, a battle between freedom and tyranny, it was a battle between all human values and the enemies of humanity.” The clarity of these (mainly Muslim) soldiers who beat an international army of Islamists underscores the not-knowingness of Mehdi Hasan et al.

The following set of posts—by Donna Gaines, George Held, Hans Koning, Wendy Oxenhorn, Fredric Smoler, Laurie Stone, Kurt Vonnegut, and Peter Lamborn Wilson—mixes pieces from First‘s back pages with writing by authors who published their first thoughts on 9/11 in other places. B.D.