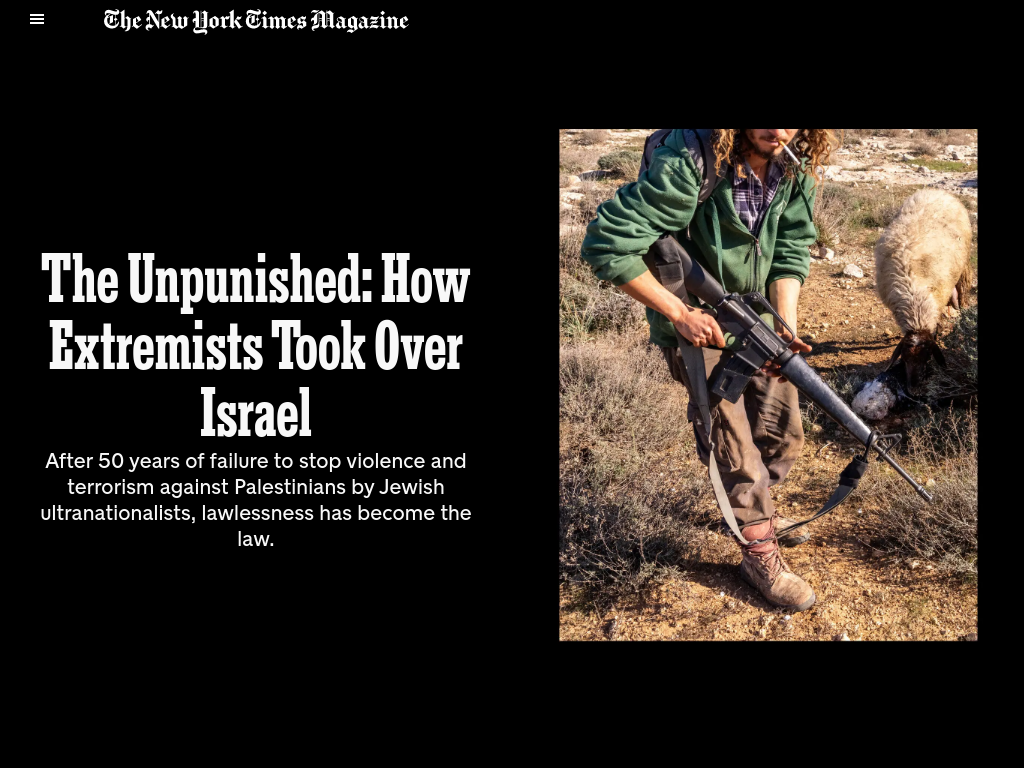

This long investigative report (published in the Sunday Times Magazine on May 16) by Ronen Bergman and Mark Mazzetti should become the most consequential piece of magazine journalism since Ta-Nehisi Coates published “The Case for Reparations” in The Atlantic ten years ago. May it be read in Israel where the public has become ever more impervious to crimes committed against Arabs. One of Israel’s extreme right-wing pols has condemned the Times piece as a “blood libel.” But Itamar Ben-Gvir — the ultra-settler who’s been Israel’s Minster of National Security since 2022 — seems to be in avoidant mode. This swatch from the article, detailing Ben-Givr’s support for mass murder and assassination, suggests why he might be betting evasion is his best option…

World

Tel Aviv Tell

I am not a professional poet

I’m not a reporter of today’s news

I see what I see,

and before I finish the telling

something else happens to me.

American Prism (Campus Diary)

The morning after the night raid, I woke up and checked my phone to see University security service’s automated message sent at 7:02 A.M.: “Quad cleanup.” I cringed. I texted a friend who had been involved from the start with the Encampment and checked the school’s paper The Maroon. Their live updated coverage had been one way of keeping up with goings on at the Quad. Like most students, I went in, and out, of the Encampment: meeting friends; nodding to acquaintances; hearing about campers’ fears and strategy; attending a Palestine-activist professor’s teach-in (“genocide isn’t complicated”); taking in kids’ play and an inter-faith call to prayer. Only snippets, perhaps, compared to those who stayed for the week and kept up chanting all night against the university police raid, but it was enough to give me a sense of the moment, and place.

On the Road with R.H. Blyth (II)

“Autumn arrives in early morning, but spring at the close of a winter day…” Elizabeth Bowen’s apercu is worthy of the seasonal sense that suffuses haiku, though it didn’t really work for me this year. Winter went away yet I kept waiting on the soft evening with Change in the air. At least I didn’t miss this…

The Humor of Senryu

The bulk of what follows comes from Chapter 18 of R.H. Blyth’s “Japanese Life and Character in Senryu,” though these excerpts may also be found in the posthumous best-of Blyth, “The Genius of Haiku.” (A book with a title that has a double-meaning.) The opening is from Blyth’s introduction to “Japanese Life.”

The fundamental thing in the Japanese character is a peculiar combination of poetry and humour, using both words in a wide and profound yet specific sense. ‘Poetry’ means the ability to see, to know by intuition what is interesting, what is really valuable in things and persons. More exactly, it is the creating of interest, of value. ‘Humour’ means joyful, unsentimental pathos that arises from the paradox inherent in the nature of things. Poetry and humour are thus very close; we may say that they are two different aspects of the same thing; Poetry is satori; it is seeing all things as good. Humour is laughing at all things; in Buddhist parlance, seeing that ‘all things are empty in their self-nature’, and rejoicing in this truth.

The Commons, the Castle, the Witch, and the Lynx

One day at Crottorf we eat mouthwatering strawberries and yogurt for our lunchtime sweet.

Crottorf is the name of a castle, or schloss, in Westphalia, Germany. Twenty one of us are assembled from around the world to discuss the commons. We come from India and Australia, Thailand and South Africa, Brazil, Italy, Germany, Austria, France, England, Greece, California and the Great Lakes. It is midsummer. Surrounded by green meadows and cool forests, the castle seems sprung from a German fairytale, a piece of paradise. Indeed the Italian plasterer said as much in 1661 carving onto the hallway ceiling the words,

Un pezzo del paradiso Caduto

de cielo in terra

For three days we sit in a circle, twenty-one of us, discussing, if not heaven on earth, then the commons.

“Rap is Clear, So Write Clear” (Redux)

Iranian rapper Toomaj Salehi was sentenced to death on April 24 for lyrics that excoriated the Islamic Republic’s rulers and enablers. His uncle tweeted a message for the Iranian diaspora that should be heard by every believer in free speech…

The uncle of imprisoned Iranian rapper #ToomajSalehi has a message for Iran. pic.twitter.com/fi2XUrnAaO

— Chelsea Hart چلسی هارت (@chelseahartisme) April 26, 2024

xxx

The following First dispatch was originally posted in January, 2023…

Toomaj Salehi has been imprisoned and tortured by Iran’s regime scum who hate how his lucid rap exposes “the filth behind the clouds.” You can find out more about his music and the international campaign on his behalf here. Toomaj should be free as a bird, free as the Iranian woman he images, sans hijab, “…liberty’s mane blowing in the wind.”

Weberian at the Gates (with “Haaretz” Interlude & Post-Bust Postscript)

“My mind is closed,” said a protestor at one of last week’s anti-Israel rallies outside Columbia’s gates. Yet she flinched at her own words once they came out of her lips. (No doubt she’d meant to say, “My mind is made up.”) I repeated what she’d said back to her. While I wished she wouldn’t shake it off too fast, there was no gloat in my game. Maybe I had a clue I’d be playing gotcha with myself soon enough.

The Columbia building occupation on Monday night had me living in contradiction, twisted and turning. I started with a hard bias against the spectacle of Ivy guys with keffiyehs and hammers.[1] But I was slain by the occupiers’ choice to rename Hamilton Hall “Hind’s Hall” in tribute to Hind Rajab, a 6-year-old Palestinian girl killed by Israeli tanks in the war against Hamas. Blunt force against property (not people) may be justified if the aim is to fix attention on the pain of others.

I wasn’t much more subtle than the window-breakers on the evening of the day last week when Iran’s regime sentenced rapper Toomaj Salehi to death for exposing the “filth beyond the clouds” of Islamism. It was my invocation of Toomaj’s case that provoked the respondent at the rally who copped to her closed mind.

No Way Out (Yet)

Early on some people talked about changing algorithms and AI, but I don’t know anything about precisely how IDF calculations and behavior have changed since October 7th. My rough impression, drawn from people who know the country much better than I do, is that the IDF was usually more scrupulous before October 7th than it has often been since, that minimizing civilian deaths is now of less concern to the military, and the details of those deaths is of less concern to other Israelis. Friends who follow Israeli politics closely say that many things do concern and for that matter enrage the electorate: the failures of the IDF before the war, perhaps also during it, the possibility of their government’s strategic vacuity, its apparent cynicism, ultra-orthodox draft evasion and political extortion, also many other things, above all how this war can end with what people at first called “deterrence restored”, but Palestinian civilian casualties unintentionally inflicted while trying to destroy Hamas does not seem to make the list.

Frau Gertrude Kugelmann and the Five Gates of Marxism

Open one of the gates to Marxism — “The Working Day” chapter in the first volume of Capital — and you’ll find paragraphs with equations (“As the working-day is A—–B + B—–C or A—–C, it varies with the variable quantity B—–C…”) Stones in your pass-way? Yup. Yet once you’re through the gate, you’ll see a path that leads to a life in struggle. You can’t help but wonder if you’ll be worthy. Not that you’ll feel a need to be (what Karl said he wasn’t) a Marxist, but you’ll always wish to come down on the commoners’ side of class conflicts. And the older you get, the more you’ll suspect the only regard that matters comes from militants with the brains to turn tears into controlled rage as Marx does throughout his “Day”…

Afropean Fraternity

https://youtu.be/pXx7bT282dk?si=xdzhI2A0ZEAPKtHF

Headie One and Koba LaD are brothers under the Channel. Their rap song, “Link In the Ends,” establishes a connection between French Banlieue and English council estate.

Pop History Play

Let’s start with a hypothetical. Suppose you’re 21 years old, you’re a raging Anglophile obsessed with British music, culture, and history, and you’re in London for the first time ever, with a flat to yourself for 1 week. For that week only, you have no responsibilities and are free to do whatsoever you fancy, in this city which Samuel Johnson once remarked that to be tired of is to be tired of life. How do you choose to spend your time?

Hunger From a Great Height

(Gaza Feb 29 2024)

A small grey rectangle

The aid truck arrives

Iron filings converge upon a magnet

Ants swarming a dropped chocolate

They may have weapons

hidden in their skeletal hands

Their hunger may be explosive

Forces of Victory

Today in Dakar, during the inauguration of Sénégal’s new president, Bassirou Diomaye Faye put on a heavy gold necklace signifying he was “Grand master of The Order of the Lion.” The ceremony made me think first of Les Lions — Sénégal’s national soccer team — but I also heard echoes of Shelley…

Rise like Lions after slumber

In unvanquishable number–

Shake your chains to earth like dew

Which in sleep had fallen on you–

Ye are many — they are few.

Faye’s party won a landslide victory, though he was released from prison just ten days before Sénégal’s March 24th election (after eleven months in pretrial detention on a bogus charge)…

A few hours after the polls closed, partial results were already pointing to a first-round winner: Bassirou Diomaye Faye, the candidate of the most outspoken opposition to the incumbent government, and second in command of the African Patriots of Senegal for Work, Ethics and Fraternity party (PASTEF). Faye will be the youngest and most unexpected president in the history of independent Senegal.

Before his presidential candidacy, Faye was little known to the Senegalese public, working in the shadow of party leader Ousmane Sonko. Sonko, also a former tax official [and another victim of a rigged judicial proceeding] … gained popularity, especially among young people, for his highly critical discourse on the traditional political class and for his promises of a radical break from how the country has been governed for decades.

I flashed on Shelley again when I saw this photo of the grey-haired Maitre Cire Cledor Ly at the inauguration…

Rape? What Rape? (Denial as a Tool of Liberation)

Great philosophers can make great errors when they confront things that challenge their closely held beliefs. Theodore Adorno, a brilliant critic of classical music, wrote ignorant essays about pop and jazz. Noam Chomsky, whose work is fundamental to modern linguistics, has a naive grasp of how media operate. Michel Foucault, whose writing on discourses and authority shaped postmodern thought, regarded the Ayatollah Khomeini as a guide to liberation from Western materialism. And then there’s Judith Butler.

If Gaza’s Children Starve, Israel Will Lose Its Moral Legitimacy Forever

An editorial in Haaretz…

The fighting in Gaza must stop. Not tomorrow. Today.

All available resources must immediately be directed to stopping the unprecedented famine that is underway in that embattled sliver of land that has already seen unspeakable suffering. As bad as the Hamas attack on Israel on October 7 was, the people and government of Israel must now recognize that today not just the country’s security but its legitimacy are at stake as never before.

Gaza Insta (The Children at Risk NOW!)

View this post on Instagram

On the Beach

View this post on Instagram

PTSD & Seth Lorinczi’s Psychedelic memoir, “Death Trip”

I used drugs—marijuana, LSD and ecstasy—in the Sixties but I never thought of them as therapeutic. The author, Seth Lorinczi, and his new autobiographical book, Death Trip, A Post Holocaust Psychedelic Memoir, has opened my eyes as never before to the idea that psychedelics can help heal the trauma of the Holocaust. In Lorinczi’s telling of the story, psychedelics rescued him, psychological speaking, from the legacy of Fascism, World War II and the extermination of millions of Jews.

On the Road with R. H. Blyth

I found the first book of R. H. Blyth’s four volume set, Haiku, (originally published between 1949-1952) in a used book store on St. Mark’s Place. If haiku seems no more pertinent to you than, say, heraldry—one more subject about which even an informed person “need not be ashamed to know nothing”[1]—you may be mollified to hear I had an excuse to check Eastern Culture since I was Christmas shopping for a nephew who’s on his way to Japan this spring. The book’s cover—“Oriental brown simple rough peasant cloth”—got me to open “the Blyth Haiku bibles” (pace Allen Ginsberg, Allen Ginsberg). I fell in…

“Plop!”

To quote the last line of “the most famous haiku” with frog-and-pond as translated by Blyth—scholar-gypsy who brought the East to Beats and Salinger (see J.D.’s bow to Blyth in “Seymour, An Introduction”: “…haiku, but senryu, too…can be read with special satisfaction when R. H. Blyth was on them. Blyth is sometimes perilous, naturally, since he’s a highhanded old poem himself, but he’s also sublime.”)

Poetry is Everyday Life

This is a chapter from Blyth’s first book, Zen in English Literature and Oriental Classics.[1]

…

From Aristotle down to Arnold it was considered that a great subject was necessary to the poet. Arnold says that the plot is everything. It is useless for the poet to

imagine that he has everything in his own power; that he can make an intrinsically inferior action equally delightful with a more excellent one by his treatment of it.

Wordsworth stands outside this tradition by instinct and by choice. He chooses the aged, the poor, the idiot, the vagrant, but does not endeavour to make them “delightful” at all.